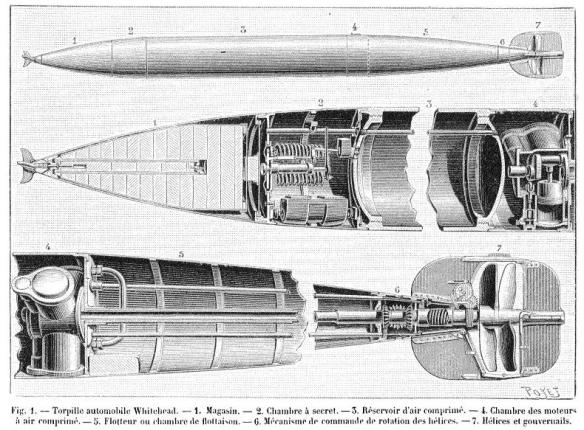

Whitehead torpedo mechanism, published 1891.

Potent new technology, notably mines, torpedoes and submarines, had implications for classical maritime warfare that, from the 1880s, fascinated theorists such as the Russian Admiral Stepan Makarov and the French Jeune École. By threatening the supremacy of the battleship, such devices seemed to herald a revolution in the composition and tactics of fleets. The earliest locomotive torpedoes – self-propelled weapons that travel underwater and which, like submerged mines and spar torpedoes, are designed to detonate against or close to the underside of a target – date from the 1860s. The invention of a Captain Luppis of the Austrian Navy, the concept was developed between 1864 and 1866 by Robert Whitehead, a British engineer who managed a factory at Fiume in Hungary. Initially known as the ‘Luppis-Whitehead Fish Torpedo’ but, later, simply as the Whitehead Torpedo, this device carried a high-explosive warhead in its nose and was powered by com- pressed air. In 1868, an important refinement was made to it through the incorporation of ‘The Whitehead Secret’, a depth-controlling mechanism that ingeniously combined a pendulum with a hydrostatic valve. Further improvements to the size, speed, range and payload of such torpedoes were achieved during the next three decades, while the addition of gyroscopic steering systems – the first of which was developed by an Austrian engineer, L. Obry of Trieste, around 1898 – greatly enhanced their accuracy. Indeed, by 1900, torpedoes that could propel a 100- kilogram, gun-cotton warhead at up to 29 knots over a range of 800 metres had been perfected.

A Whitehead Torpedo was first used in anger by the British frigate Shah in 1877. Its quarry, a Peruvian rebel vessel, the Huascar, managed to evade the weapon, which, at this juncture, was too lacking in pace and reach. The following year, however, the Russians sank a Turkish ship in Batum harbour with two torpedoes fired from some 80 metres away. This success helped highlight the potential of these novel armaments and, during the 1880s, they were adopted by almost all navies. Tremendously destructive, they seemed to threaten even the sturdiest of warships and precipitated extensive changes in the structure of fleets and individual vessels alike. Naval architects began to add dense belts of armour to the waterlines of capital ships, while some theorists called for radical alterations to the composition of fleets in the light of the apparent vulnerability of large, expensive vessels. Above all, in Les Torpilleurs autonomes (1885) and La Reforme de la Marine (1886), the bible of the Jeune École, Gabriel Charmes advocated a division of labour within the French Navy. Instead of investing its resources in a comparative handful of sizeable, armoured ships bearing a multiplicity of weapons, the fleet should, he argued, comprise lots of units made up of small vessels that would rely less on metal plating than on numbers, elusiveness, speed and manoeuvrability for their protection. Geared to particular combat roles, some should carry either guns or torpedoes, while others should be primarily designed as rams. Whereas part of the fleet should be geared to operations on the high seas, the rest should be custom-built for patrolling coastal waters.

Although the principle of the division of labour was gradually adopted by navies, it was not to be along the lines envisaged by Charmes. However, the advent of effective mines and torpedoes certainly necessitated changes to maritime strategy and tactics, as well as inspiring the creation of entirely new classes of naval platforms and other innovations. Not only was the waterline armour on many ships greatly enhanced, but also their interiors were reinforced through the adoption of cellular structures built around water-tight bulkheads. Special nets were also devised to screen harbours and moored vessels from torpedo attacks. Besides such passive defences, a new type of plat- form had to be developed that could actively counter the novel threat posed by torpedo-boats. The destroyer, as it became known, was a sleek, fast vessel armed with guns and torpedo tubes. Britain’s first, HMS Havock, which was finished in 1893, was capable of 26 knots, while HMS Viper, completed six years later, could, thanks to her steam turbines, a propulsion system first exhibited by Charles Parsons at the 1897 Spithead review, achieve 34 knots.

Speeds of this magnitude enabled destroyers to threaten small and large vessels alike; even capital ships could prove vulnerable to audacious torpedo strikes. However, the coupling of locomotive torpedoes – which could be fired either from above the water-level, usually from swivel- mounted pods, or from fixed, underwater tubes – with submersibles created unprecedented possibilities for the mounting of insidious attacks. The notion of a submarine was an old one: as early as 1776, during the American Revolution, a submersible devised by David Bushnell had been used in an unsuccessful mine-laying attack on HMS Eagle; while the Nautilus, a craft devised 21 years later by Robert Fulton, had briefly caught the imagination of Napoleon. We have noted, too, how in 1864 the Confederates’ hand-cranked Hunley sank the USS Housatonic with a spar torpedo. By the 1890s, however, sizeable, mechanically powered submarines were being perfected, not least by John Philip Holland, an American engineer who was eager to create a weapon that might weaken Britain’s domination of the seas. Somewhat ironically, the Royal Navy ultimately acquired his patented, 1898 design for a submarine that was driven by electrical storage cells when submerged and a petrol engine when cruising on the surface.