Davis could not stay away. He may have been on the field with Lee on June 27 as Confederate troops went into action at the battle of Gaines Mill. The following evening he inspected the lines of Generals Benjamin Huger, Lafayette McLaws, and John B. Magruder on the south side of the Chickahominy. Lee had, in some of his communications, implied for Davis a more direct supervisory role in this sector, almost suggesting that he considered the president—or that the president considered himself—a sort of informal commander for the three divisions holding the line south of the river. As Davis visited these commands that night, he gave the officers there his opinion “that the enemy would commence a retreat before morning” and “gave special instructions as to the precautions necessary in order certainly to hear when the movement commenced.” If the enemy could be attacked while withdrawing, the Confederates would gain a large advantage. Satisfied, Davis returned to Richmond, but during the night the Federals did indeed make good their retreat undetected by the Confederates opposite them.

Lee faithfully informed Davis of the army’s progress throughout the week, and the president carried on his more conventional role of forwarding reinforcements to the front. At Frayser’s Farm, however, the president was back in the thick of the action. Coming into a forest clearing about 2:30 p. m. on that last day of June, Lee discovered Davis in conversation with Major General James Longstreet, a senior division commander. The president was ready for Lee this time and not about to be caught off guard as he had been at Mechanicsville. “Why, General,” he exclaimed, “what are you doing here? You are in too dangerous a position for the commander of the army.”

Lee, who was exasperated almost to the limits of his considerable patience by the failures of his staff and subordinate generals to carry out his plans, replied, “I’m trying to find out something about the movements and plans of those people,” meaning the Federals. “But you must excuse me, Mr. President,” he continued, “for asking what you are doing here, and for suggesting that this is no proper place for the commander-in- chief.” Of course, Davis could have answered that as commander-in-chief he would go wherever he pleased, but this was Lee to whom he spoke, a man to whom he inwardly deferred as his superior morally if not legally. Instead, he was able to dodge Lee’s suggestion. “Oh,” he answered, “I am here on the same mission that you are.” With that Lee could do nothing, and the president stayed. Within minutes, however, the clearing came under heavy bombardment. A courier was wounded and several horses killed. The Confederates, generals, president, and all, quickly vacated the area.

Later that same day, when Brigadier General Theophilus Holmes’s green division broke under the fire of Federal artillery, Davis endeavored to rally the fleeing troops. He had just succeeded in stopping them when, as he described it, “Another shell fell and exploded near us in the top of a wide-spreading tree, giving a shower of metal and limbs, which soon after caused them to resume their flight in a manner that plainly showed no moral power could stop them within the range of those shells.” Still within that range, Davis again encountered Lee, who at considerable personal risk was surveying the ground in search of a less exposed position for Holmes’s battered division. Again the president remonstrated with his top general for exposing himself to the enemy’s fire. It may have been another ploy of the president’s to avoid being sent away himself, but it was probably sincere at the same time. Davis had lost Sidney Johnston, killed by enemy fire at Shiloh, and Joe Johnston, wounded at Seven Pines. He could not afford to lose Lee, but, besides, he was also coming to feel a genuine affection for the reserved and respectful Virginian.

This time Lee made no effort to shoo the president off the battlefield. The frustrated general merely explained that going to look the ground over for himself was the only way he could get the information he needed.

The next day—July 1, 1862—saw the disastrous assault on Malvern Hill. Again Davis seems to have been lurking in the area. The morning after the failed attack, the president, accompanied by his nephew Colonel Joseph Davis, paid a call to Lee’s headquarters at the Poindexter house. Lee was present along with Jackson and a number of staff officers. Curiously, the general seems to have been surprised to see Davis, perhaps because of the cool temperatures and incessant rain. Dr. Hunter McGuire, Jackson’s medical director, noticed that the apparently startled Lee addressed Davis not as “Mr. President,” but rather as simply “President.”

“President,” Lee said, “I am delighted to see you.” Davis greeted Lee and his aide, Major Walter Taylor, before turning with a questioning look toward the ungainly but obviously high-ranking officer who stood stiffly nearby. Davis and Jackson had never met, and their official relations had not been happy. The president’s meddling had driven Jackson to submit his resignation six months before. Jackson had felt that his authority had been usurped when a subordinate had convinced Richmond authorities to overrule one of Jackson’s orders. The government ultimately reversed itself and supported Jackson, and he had retracted his resignation, but the general’s feelings remained bruised. When Davis had come in, McGuire had whispered to Jackson the identity of the visitor and Jackson, ever mindful of his duty to a military superior—even one he disliked—came to attention, as McGuire put it, “as if a corporal on guard, his head erect, his little fingers touching the seams of his pants.”

“Why President,” Lee interjected, apparently still trying to regain his mental equilibrium, “don’t you know General Jackson? This is our Stonewall Jackson.” Davis bowed. Stonewall saluted. With that unpleasant preliminary out of the way, Davis and Lee got down to the business at hand. Spreading their maps on the dining room table, they began to discuss the tactical situation. Lee explained the previous day’s action and the subsequent withdrawal of McClellan’s army. As the discussion continued, Dr. McGuire noticed something. “Every now and then,” he later wrote, “Davis would make some suggestion; in a polite way, General Lee would receive it and reject it. It was plain to everybody who was there that Lee’s was the dominant brain.”

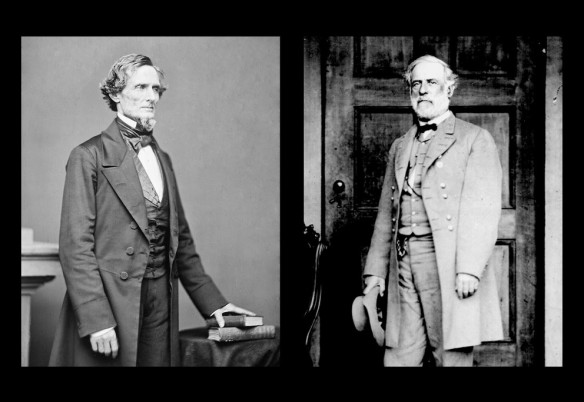

As the Seven Days’ battles ended, the basic boundaries of the working relationship between Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee had been set. Lee had established that he, not Davis, would fill the role of field commander. Davis had made it plain that he would continue to take a close interest in the army and, when possible, would endeavor to view its operations in person. Each had won a large measure of respect from the other. Davis must have impressed Lee with his battlefield courage as well as his often sound tactical and strategic advice, despite the frequency with which the general had to reject his less practical suggestions. The president had come to a level of deference to Lee that he felt for only a handful of other individuals in his life. On such persons he tended to rely with almost childlike trust, and this was no doubt the basis—along with Lee’s superior military abilities—for the mental ascendancy the general had gained over the president.

The results of this relationship were both good and bad for the Confederacy. Lee, a general of brilliant abilities, was allowed free reign and given full support through the rest of the war in Virginia. No setback could shake Davis’s confidence in him, nor could personal problems arise of the sort that had strained civil-military relations and hampered Confederate operations during the commands of Beauregard and Joe Johnston. If Lee failed to conquer a peace, it would not be for any failure by Davis to exert his considerable organizational talents in his support.

Yet if Lee had a fault as a general, it was an excess of the very audacity that made him effective. Left to his own devices, he would gamble too often and for very high stakes. He gambled with soldiers the South could ill afford to lose. Caught up in the events and emotions of campaigning, with final victory beckoning to him—his to be had for one more infantry assault, for one more daring thrust—Lee was often too close to the action to see the fine line that separated daring from madness, at least within the context of Davis’s overall defensive strategy. A firm and wise hand was needed, a leader removed from the immediate turmoil of battle and able to judge the South’s prospects against its dwindling resources. That hand should have been Jefferson Davis’s, but the president was unable to fulfill the role, first because he desired the role of field commander for himself and second because he made his field commander an alter ego. He would, in the end, give Lee everything the president of the Confederacy could have given except the strategic guidance of a wise commander-in-chief.