In 1543, Francis attacked Charles in the Low Countries and northern Spain; in the following year, the French won the Battle of Ceresole in Piedmont. Although the infantry were well-matched, the superior and more numerous French cavalry defeated their opponents and the landsknechts withdrew, their casualties over twenty-five per cent. The relatively immobile artillery played little role in the battle.

The northern campaigns of 1544 proved as cautious and indecisive. Henry VIII had broken with his Valois ally in 1543, and the next year he landed the largest English army of the Renaissance – over 30,000 men – in northern France. Henry’s goal was nothing less than the seizure of Paris, operating in tandem with an Imperial force invading through Champagne under Charles V’s personal command. It was a potentially very powerful strategy, but both Imperial and English offensive operations bogged, the emperor’s in front of St Dizier, which fell after a month’s siege, and Henry’s before the city of Boulogne, which fell on 14 September 1544.

The forces involved in the confrontation of summer 1544 were large. The Emperor was planning his force at Speyer from February but it took time to bring his troops from Germany together with those from the Low Countries. In May Gonzaga recaptured Luxembourg. When the siege of Saint-Dizier began the imperial forces came together and amounted to 35,000 (30,000 infantry) and 60 pieces of artillery. Meanwhile, Henry VIII advanced with a similar number against Boulogne and Montreuil.

On 9 October the French attempted to win the city back by a camisade, a sudden night assault with the men wearing white shirts (camises), such as the Spanish had performed so brilliantly at Pavia. The assault was initially successful, but the French attackers prematurely turned to plundering the city and were routed by an English counter-attack.

The outcome of the campaign was really determined by the heroic defence of Saint-Dizier, which lasted until 17 August. Charles continued his march through Champagne and then entered Soissons, though with supplies shrinking. Francis had established a fortified camp at Jalons, west of Châlons, with a force very similar in numbers to the Emperor’s but was reluctant to counter-attack. Charles, running out of supplies and without help from Henry VIII, abandoned his attack on Paris on 11 September. Henry VIII, though, managed to capture Boulogne on 13th, five days before Francis and the Emperor agreed the peace of Crépy. The peace shelved the major problems. The status quo of 1538 was restored and marriage alliances proposed that would give Orléans either the Low Coun- tries or Milan. But the treaty was unworkable, as it would have aggrandised the King’s younger son too much. The fact that Henry VIII had snatched Boulogne just before the peace made him reluctant to participate and so the war with England continued until June 1546, the main engagements being a naval war in the summer of 1545 that saw a French raid on the Isle of Wight and the sinking of the Mary Rose and a French expedition to help allies in Scotland. Francis may well have been on the verge of returning to war with the Emperor in 1547 but his death put an end to preparations.

Renaissance Armies: The English—Henry VIII

The service of the English army of the 16th Century was varied, if on a relatively small scale: a couple of expeditions against France, continuous trouble and two major conflicts with Scotland, lengthy wars in Ireland, aid to both sides in the Netherlands and to the Huguenots in France, plus preparations against various invasions which never came. In itself, the army is of particular interest, firstly in weaponry, with the insular retention of bill, cavalry lance, and, above all, longbow, long after their abandonment elsewhere; secondly in forced reliance on a national militia system throughout what was generally the age of the mercenary.

Englishmen had been compelled to keep arms according to their wealth (and in some cases their wives’ wardrobes—a silk petticoat let you in for the expense of light horseman’s equipment!) since the Assize of Arms of 1181, and the 16th Century effectively saw the continuance of this system, though with modifications.

All eligible were compelled to muster for inspection at varying intervals (up to twice a year in times of danger), the system being generally administered on a county basis, and run by Commissioners of Musters (replaced, from the reign of Mary, by the new Lords-Lieutenants). The Clergy, and Lords and their retainers, had similar obligations, administered separately. By the end of the century the militia, in theory at least, totaled a million men.

At first the troops returned home after inspection, unless an invasion threat caused them to be kept mobilized—Henry VIII kept 120,000 men on foot for a whole summer.

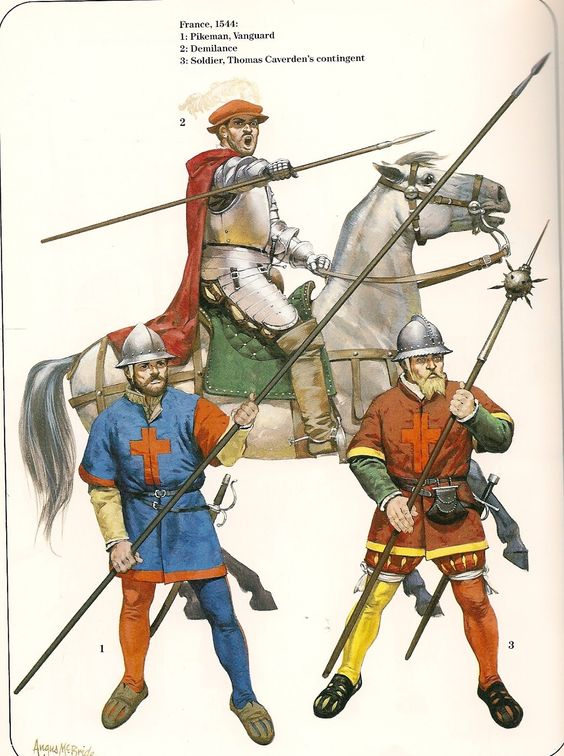

In the early 16th Century, nearly all were the traditional billmen and longbowmen, both usually equipped with a jack (a waist or knee length coat “quilted and covered with leather, fustian or canvas, over thicke plates of iron that are sowed in the same”), and with a simple rounded helmet of “skull” or sallet type. Even by the 1550s this was still largely true, corselets and morions being rare, and multi-layered canvas jackets or even mail shirts being still favored.

Henry VIII, the only military-minded English monarch of the period, began reform. As well as instituting home production of artillery and armour, he imported weapons in quantity (many are still at the Tower) and encouraged the adoption of artillery, the pike, and hand firearms. However, among 28,000 English foot taken to France in 1544, there were less than 2,000 arquebusiers, and billmen outnumbered pikemen three or four to one. Henry had to hire Spanish and Italian arquebusiers, and German pikemen.

The word “Regiment” was used in Henry VIII’s time to describe one of the three medieval-type battles into which armies were still divided (in 1544, 13,000 to 16,000 strong). Each of these would mass its pikemen and billmen together in from one to three large blocks, with wings of archers and other shot operating on their flanks. “Regiment” still had a very vague meaning in the mid-16th Century—all the troops operating in the Netherlands, 6,000 or more, forming one “regiment”—but by the later part of Elizabeth’s reign, regiments were fairly definite organizations, commanded by a colonel. They could be of ten companies, as later, but in Ireland were often of five.

“Men-at-Arms”, with heavy lance, full armour, and often barded horse, were still used in the first half of the century, but were few in number, though of high quality. In 1544, Henry VIII had 75 “Gentlemen Pensioners” or Household cavalry, and 121 Men-at-Arms. Individual noblemen would also serve in full plate. The appearance of such troops would be much the same in any army, though Englishmen might wear rounded Greenwich armour.

Much more numerous were the “demilances”, with corselet only, or three-quarter armour, open burgonet, and unbarded horse. These men carried a lighter lance, and later pistols, and formed the main English heavy cavalry up to the end of the century.

Cavalry were always in short supply in English armies; HenryVIII supplemented them with Burgundians, and Germans with boar-spear and pistols.