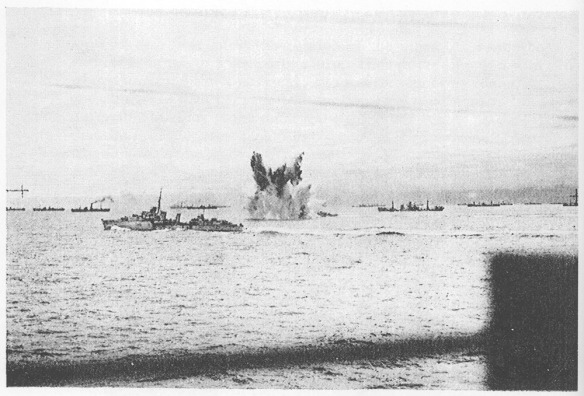

Convoy to North Russia PQ 18, September 1942. Destroyer Eskimo in foreground.

Track of PQ 17, with approximate localisation of the convoy’s losses.

The damage caused to the Allies by the loss of PQ17 reached far beyond burning ships and dead bodies on the frozen waters of the Arctic. Soviet authorities accused the Royal Navy of cowardice and Allied commanders of lying about the extent of their losses – refusing to believe that so many ships could be lost. In the United States the well-known Anglophobe Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of Naval Operations, was enraged at the loss of American shipping (fourteen of the merchants sunk) and refused to cooperate with the Royal Navy any further within the region, moving his forces to the Pacific. To add insult to injury the ships of QP13 that had evaded attack had suffered four merchant ships sunk and two damaged after the convoy was guided mistakenly into a British minefield off Iceland. The Germans’ success had exceeded their greatest hope. Of the ten Eisteufe’ boats only U408 and U657 failed to successfully score a torpedo hit on target; Kaptlt Heinrich Göllnitz’s U657 was forced to return to Narvik after depth charge damage caused a fuel leak. Determined to inflict a second serious defeat upon what was presumed to be the imminent arrival of PQ18, Oesten formed the group Nebelkönig for the end of July between Iceland and Jan Mayen. By the early part of August the group comprised ten boats, but PQ18 had been postponed.

Despite howls of Soviet protest, British strength was required elsewhere for Operation Pedestal within the Mediterranean. Following the catastrophe of PQ17, the Royal Navy was determined that PQ18 would not sail until much greater escort strength could be provided. It would be September before the convoy finally departed for Russia.

On 2 September PQ18 departed Loch Ewe, Scotland. Comprised of forty merchant ships (twenty American, eleven British, six Soviet and three Panamanian) a heavy escort was laid on which included an aircraft carrier for the first time: HMS Avenger carrying ten Hurricane fighters and three Swordfish torpedo bombers. A combined Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force task force of Hampden torpedo bombers, Catalina and Spitfire reconnaissance aircraft had also transferred to Vaenga airbase near Murmansk for potential operations against Tirpitz should she put to sea.

U-boat missions against PQ18 were planned, code-named Operation Eispalast. The outgoing QP14 was included, but deemed of secondary importance. Once again, large surface ships were readied for potential use against the convoy, although, as always, Hitler’s strict criteria would be used to determine their activation. They moved north to Altafjord on 10 September – Admiral Scheer narrowly missed by four torpedoes from HMS Tigris while in transit – and remained ready for sailing orders that never came. Hitler’s paranoia of losing his large ships rendered them once again useless.

Meanwhile PQ18 was detected briefly by Luftwaffe reconnaissance on 8 September. Oesten brought together a new U-boat group: Trägertod (Carrier killer). By 10 September U88, U403 and U405 were en route from the Spitsbergen and Bear Island area to a patrol line further west; U589, U377, U408 and U592 raced to join them. Additionally, U435 and U457 were scheduled operational by 12 September at Narvik, and U378 at Trondheim: and all would sail. U703 was refuelling at Harstadt, bringing the group number to eleven. Four others were earmarked for operations against QP14 following refuelling at Kirkenes: U255, U601, U456 and U251. At 1.20 p.m. on 12 September, Luftwaffe aircraft sighted PQ18 again, U405 making contact soon after and staying on station as beacon boat. The U-boats gathered, one of the next boats to begin shadowing was Kaptlt Bohmann’s U88; Bohmann was himself detected ahead of the convoy by HMS Faulknor of the ‘fighting escort’ – U88 accurately depth charged and sunk with all forty-six crewmen aboard.

The escorts and Avenger’s aircraft were kept busy attempting to force shadowing boats away from PQ18. However, at 9.52 a.m. on 13 September, Kaptlt Reinhard von Hymmen made the first torpedo hit on PQ18 when 3,559-ton Soviet steamer Stalingrad was sunk with one of three torpedoes, the ship going under in less than four minutes laden with ammunition, aircraft and tanks. Twenty-one of the eighty-seven crew were killed and the master, A. Sakharov, was last to leave the sinking ship, spending forty minutes in the water before being rescued and going on to act as pilot for the convoy. Von Hymmen had missed Stalingrad with two of his three torpedoes, but one had passed by the Soviet ship and hit 7,191-ton American Liberty Ship Oliver Ellsworth, the steamer executing a hard left turn to avoid the crippled Russian. The American ship was abandoned even before it had ceased moving, three of four lifeboats swamping and throwing their occupants into the water, though all except one US Navy armed guard were rescued. The wreck was finally sunk by shells from escorting ASW trawler HMT St Kenan.18

At almost the same time as Von Hymmen, Kaptlt Hans-Joachim Horrer fired two torpedoes toward HMS Avenger from U589 claiming to have scored at least one hit, although his shots missed. It may have been the detonations from U408’s attack that were heard through the freezing water aboard the submerged boat. That same day Horrer pulled four Luftwaffe airmen from their escape dinghy after their aircraft had been shot down during He111 torpedo bomber attacks that destroyed eight ships for the loss of the same number of aircraft. The airmen did not have long to enjoy their good fortune as the following day U589 was sighted by one of Avenger’s Swordfish. Though the biplane was chased away by a Luftwaffe Bv138 flying boat, the sighting brought destroyer HMS Onslow to the scene, catching U589 on the surface. Crash-diving, U589 was depth charged relentlessly by the destroyer until fuel oil, green vegetables and pieces of U-boat casing floated to the surface marking the grave of all forty-four crew and their four Luftwaffe passengers.

That same day there remained only one other confirmed sinking from PQ18. At 4 a.m., Brandenburg’s U457 hit 8,939-ton motor tanker Atheltemplar whose cargo of 9,400 tons of Admiralty fuel oil immediately began to burn. The crew abandoned ship south-west of Bear Island while minesweeper HMS Harrier attempted to scuttle the burning ship with gunfire, the attempt failing and the ship was left burning fiercely, later found by U408 after she had capsized – the hulk sent to the bottom with gunfire. Brandenburg claimed another 4,000-ton steamer sunk and two hits on a Javelin-class destroyer, but in this he was mistaken. Korvettenkapitän Rolf-Heinrich Hopman later claimed another destroyer hit on 16 September after a torpedo from U405 was heard to detonate after a run of over seven minutes. This too remains unsubstantiated, although the Allies definitely found Brandenburg’s U457 at 3 a.m. on that day. The U-boat was diving through the port bow escort screen when spotted: depth charges from HMS Impulsive destroying the boat along with all forty-five hands as oil, wreckage, paper and a black leather glove floated to the surface to mark the spot. The British illuminated the scene with a calcium flare before one further depth charge set to explode at 500ft was dropped to ensure the boat was sunk.

Elsewhere QP14 came under successful U-boat attack. Seventeen merchant ships, under heavy escort, were attacked by a total of seven U-boats that sank six ships. Strelow’s U435 sank minesweeper HMS Leda and three merchant ships: 5,345-ton American freighter Bellingham; 7,174-ton British steamer Ocean Voice; and 3,313-ton British freighter Grey Ranger during a single devastating assault on 22 September. Reche’s U255 sank 4,937-ton American PQ17 survivor Silver Sword while the destroyer HMS Somali was badly damaged by Kaptlt Bielfeld’s U703 and later sank in gale force winds while under tow.

PQ18 was judged a relative success by the Allies. Although thirteen ships in total had been lost, twenty-eight had arrived safely in the Soviet Union. Furthermore, three U-boats and forty Luftwaffe aircraft – including many skilled veterans of maritime operations – had been destroyed; the Luftwaffe were never again able to mount such strong attacks on the Russian convoys, as aircraft were gradually transferred south to the Mediterranean. The severe losses accrued by both PQ17 and PQ18 combined, coupled with demands elsewhere for Allied naval craft such as supporting Operation Torch, led to the suspension of the Arctic convoys until December 1942. Instead, independently sailing merchantmen would be despatched in what was known as Operation FB.

Between 29 October and 2 November, thirteen ships sailed at approximately twelve-hour intervals from Scotland to Murmansk. Although unescorted, there were ASW trawlers stationed at intervals along the route and local escorts available from Murmansk. From the ships that sailed, three were forced to abort their voyages and five were sunk, the remaining five reaching the Soviet Union. On 2 November ObltzS Dietrich von der Esch in U586 had already been at sea for three weeks, sailing in bad weather and suffering mechanical problems with the boat’s exhaust valves. An initial order to reconnoitre Jan Mayen was carried out before the U-boat sighted Operation FB ship Empire Gilbert and began a two-hour chase. The 6,640-ton steamer was missed by an initial double torpedo shot but hit on the port side by a second pair of torpedoes at 1.18 a.m.. The ship sank rapidly and when U586 reached the scene she was gone. The Germans pulled deck boy Ralph Urwin and gunner Arthur Hopkins aboard U586 from a floating beam, the pair barely able to move after submersion in the freezing water, and next attempted to question six survivors found aboard a raft but received no answer. Taking one more man, gunner Douglas Meadows, prisoner aboard the U-boat, U586 left the scene and later landed the three survivors at Skjomenfjord. The other sixty-four men were never seen again.

Two days later unescorted Liberty Ship William Clark was hit by a torpedo in the engine room from Kaptlt Karl-Heinz Herbschleb’s U354. A coup-de-grâce torpedo broke the ship in two and sent her to the bottom, 31 of the 71 crew either killed in the sinking or lost at sea as their lifeboats drifted away.

The final ‘FB’ ships sunk by U-boat were both destroyed by ObltzS Hans Benker’s U625 engaged upon its maiden war patrol. The 5,445-ton British steamer Chulmleigh had been bombed by Ju88 aircraft and beached on Spitsbergen’s South Cape when Benker torpedoed the stranded wreck and finished it off with gunfire on 6 November. That night he sighted 7,455-ton British Empire Sky and hit her with two torpedoes. As the steamer settled into the water a coup de grâce ignited its ammunition cargo and she exploded, flinging debris over a wide area, one piece weighing a kilogram clattering down the conning tower hatch into the U-boat’s control room. All sixty men aboard the shattered freighter were lost.