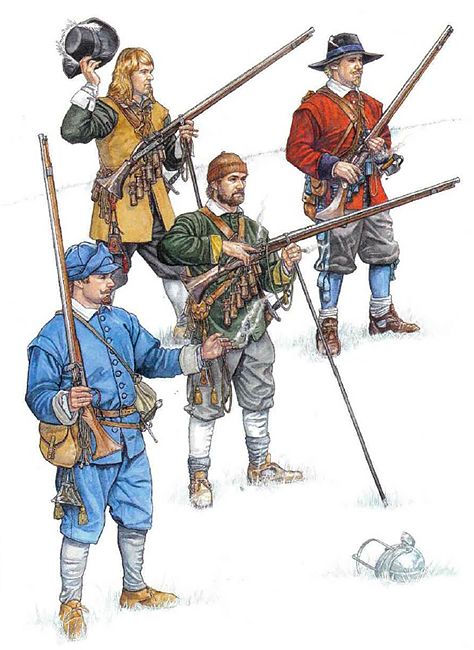

Various Musketeers

1643 the newly raised regiment of cuirassiers commanded by Sir Arthur Hesilrige

Musketeers’ equipment 1: Musketeers 2: Hats & Montero caps 3, 4: Bandoleers & tools 5: Muskets

Fighting broke out in the west even before the King raised his standard at Nottingham on 22 August 1642. At the end of July the Marquis of Hertford turned up in Bath with the King’s commission as Lieutenant General of the six western counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire and Wiltshire. Charged with distributing commissions of array to the King’s supporters in those counties, he chose to proclaim the fact not in hostile Bristol but in the rather safer atmosphere of Wells. Unfortunately, his call to arms met with a muted response, and while the local Trained Band was persuaded to muster under Sir Edward Rodney, they made it plain that they had absolutely no intention of fighting anybody. This was unhelpful to say the least, but on the other hand Lieutenant Colonel Henry Lunsford succeeded in raising some 240 volunteers for a marching regiment to be commanded by his brother Sir Thomas. Three troops of horse were also raised, two for Lord Grandison’s Regiment and the third commanded by Sir Ralph Hopton.

Meanwhile, Sir Alexander Popham was having rather better success in raising volunteers and Trained Bands for the service of Parliament. On 1 August 1,200 men were mustered at Shepton Mallet, and although Hopton turned up as well hoping to disrupt the proceedings, he hastily withdrew after counting heads. This reluctance to initiate hostilities did not last long. Just three days later the first shots were fired in a minor skirmish at Marshall’s Elm on 4 August. Although the Cavaliers claimed a famous victory, their celebrations were cut short next day when Popham moved forward with his whole force and compelled them to retreat to Sherborne.

Thereafter, there was something of a lull, but the Earl of Bedford was sent down from London to take charge, and with 7,000 men at his back, he turned up before Sherborne on 2 September. Not surprisingly the Royalists hastily threw themselves into the castle, but then finding Bedford more cautious than his numbers warranted, they reoccupied the town with some 300 foot. A rather half-hearted siege, or rather blockade, then followed, but Bedford pulled out on the 6th and fell back to Yeovil.

The following afternoon Hertford sent Hopton after them with 100 horse, sixty dragoons and 200 foot. It was intended to be no more than a reconnaissance in force, but Hopton nearly came to grief just as he was preparing to withdraw from his observation post on the curiously named Babylon Hill. Intent on watching Yeovil Bridge, the Cavaliers failed to see a party of Parliamentarians coming out of the town until it was almost too late. Sending off his foot at once, Hopton tried to cover their retreat with his cavalry. Two of his troops led by Captain Edward Stowell:

… charg’d verie gallantly and routed the enemy, but withall (his troops consisting of new horse, and the Enemy being more in number) was rowted himselfe; and Capt. Moreton., being a little too neere him was likewise broaken with the same shocke, and the trueth is in verie short tyme, all the horse on both sides were in a confusion: At the same tyme a troope of the Enemyes horse charg’d up in the hollow-way on the right hand, where (Sir Tho: Lunsford having forgotten to put a party of muskettiers as before) they found no opposicion till they came among the voluntiers upon the topp of the Hill, where by a very extraordinary accident, Sir James Colborne with a fowling gunne shott at the Captain in the head of the troope, and at the same instant Mr. John Stowell charg’d him single (by which of their hands it was, it is not certaine) but the Captain was slayne, and the troope (being raw fellows) immedyately rowted. In this extreame confusion Sir Ralph Hopton was enforced to make good the retreate with a few officers and Gentlemen that rallyed to him …

Despite seeing the Royalists off the premises, Bedford made no attempt to exploit his little victory. On the contrary, displaying his usual lack of resolution, he promptly decamped to Dorchester. Heartily glad to find him gone, the Cavaliers hung on at Sherborne until news came through on the 18th that Portsmouth had been taken by Sir William Waller. This unhappy news seems to have finally convinced Hertford that he was engaged in a hopeless task, so he abandoned Sherborne and headed north with all his forces to Minehead. The intention was then to ferry them across the Bristol Channel and march to join the King, but when they arrived in the little port it was to find only two ships there. These were sufficient to carry Sir Thomas Lunsford’s Regiment and the guns, but the cavalry had to be left behind. With Bedford closing in, there was little alternative but for Hopton to bid goodbye to Hertford and the Lunsford brothers and retire westwards into Cornwall.

Bedford made no attempt to pursue him, and instead rejoined Essex to play a less than glorious part in the Battle of Edgehill.3 This was rather unfortunate, for Hopton’s arrival in Cornwall altered the balance of power there in the King’s favour. Encouraged by the arrival of his cavalry, the local Royalists managed to bring over 3,000 men to a muster on Moilesbarrow Down on 4 October. For the most part they belonged to the Trained Bands, and although they enabled Hopton to occupy Launceston and secure the line of the Tamar, they also displayed the Bands’ traditional reluctance to cross the border into neighbouring Devon. Consequently, five of the Cornish leaders engaged to raise and maintain volunteer regiments, and with this little army at his back Hopton turned ambitious and cast his eyes on Plymouth.

As a first step they moved forward and occupied Mount Edgecumbe House and Millbrook, thus securing the Cornish side of the sound, and then forced a Parliamentarian detachment to retire from Plympton. This detachment had a curious history. At the beginning of October Lord Forbes’ regiment of Scots mercenaries, who had been carrying out a series of piratical raids on rebel-held territory in Ireland, put into Plymouth and were promptly hired to defend it. Thus fortuitously garrisoned, the town was secured pending the arrival of Bedford’s replacement, Lord Robartes, and three newly raised regiments. Two amphibious raids by the garrison on the outpost at Millbrook were beaten off, but on the night of 6 December Colonel William Ruthven, the mercenaries’ commander launched an altogether more successful raid on Modbury.

Hopton had arrived there earlier that day in an attempt to raise the Devon Royalists, but the gathering ‘was rather like a great fair’,4 and he could scarcely find enough armed men to mount sentries. Inevitably Ruthven (who had also been appointed commander-in-chief of the western forces) mounted a raid which scattered the assembled Royalists, captured the High Sheriff and very nearly snapped up Hopton as well. Then, taking no chances, instead of returning directly to Plymouth, he marched hard for Dartmouth and shipped both his men and the prisoners back by sea.

Without the Devon men there was no hope for the present of taking Plymouth, yet Hopton needed to secure a proper base where he could shelter and supply his army through the winter. An alternative had to be found, and so he turned his attention to Exeter instead. At first all went well. The city was summoned on 30 December, and Topsham was seized in order to prevent supplies or reinforcements coming up the Exe estuary. Unfortunately for the Royalists, while they were thus occupied in sealing off the seaward approaches to Exeter, Colonel Ruthven mounted a large body of musketeers on every nag he could find, and threw himself into the landward side of the city. This unexpected stroke did far more than simply dash the Royalists’ hopes of taking Exeter for as Hopton admitted:

Their expectation of ammunition, subsistence and increase from the County utterly failed, so as the army was enforced in that bitter season of the year (encumbered with all sorts of wants, and with the disorder and general mutiny of the Foot) to retreat towards Cornwall.

Baffled, the Cavaliers fell back by Crediton and Okehampton. Ruthven, indefatigable as ever, soon got on their track and, notwithstanding a creditable rearguard action at Bridstowe, he chased them all the way back into Cornwall and mounted an unsuccessful attack on Saltash. Even this minor reverse worked to his advantage for, while the Cavaliers’ attention was fixed on the town, he managed to pass a body of men across the Tamar at Newbridge. Hopton was now in a most unenviable position. Ruthven had forestalled him at every turn and was now mounting an invasion of Cornwall. What was more, additional Parliamentarian troops were known to be on the way, commanded by the Earl of Stamford who had hitherto been making a nuisance of himself in the Severn valley. Once he joined forces with Ruthven the two of them would be well nigh unstoppable.

At this point Hopton had an undeserved stroke of luck. Three Parliamentarian ships were driven by bad weather to seek shelter in Falmouth. Naturally enough, they were promptly seized by the Royalists, and the powder found on board (together with an equally welcome supply of hard cash) encouraged them to fight one last battle. At a muster held at Boconnoc on 18 January Hopton’s de facto position as commander of the Cornish army was formally confirmed6 and the decision was taken to counter-attack.

Accordingly, they marched next morning from Boconnoc, and at about noon came up with Ruthven’s army on some rising ground known as Braddock Down, just outside Liskeard. The Parliamentarians had rather more cavalry than the Royalists, but fewer infantry. Moreover, all of Ruthven’s foot were a mixture of raw country levies and Trained Bands; his Scots mercenaries had been left behind to hold Plymouth. Nevertheless his position was strong enough to give Hopton pause to think, and he drew up his army on another low hill, leaving a shallow valley between them.

For about two hours both commanders maintained their positions. Understandably enough neither general felt too keen about descending into the valley and fighting uphill. Ruthven might have done well to avoid battle altogether and wait for Stamford, but he had done well enough against Hopton thus far and he was no doubt confident of beating him again before the Earl arrived to steal his thunder. For his part Hopton was equally keen to anticipate Stamford’s arrival and so, firing two cannon as a signal, he sent the Cornish surging forward. Both horse and foot crossed the valley and advanced so resolutely that Ruthven’s men were seized with a sudden panic. The Parliamentarian foot fired just one ragged volley, and then broke and ran before the Royalists could come up with them. To add to Ruthven’s chagrin, as they streamed back through Liskeard in great disorder, the townspeople suddenly rediscovered their loyalty to King Charles and rose up against them. Afterwards the Cornish claimed to have lost just two men and, while it is likely that most of Ruthven’s men ran away too quickly to be killed, some 1,250 of them surrendered along with five good guns and all his baggage.

Otherwise, Ruthven got clean away, for the Cavaliers rested at Liskeard on the 20th, but once they had sobered up, Hopton divided his forces. One column directed upon Launceston sent Stamford into headlong retreat, while he himself marched on Saltash. Ruthven was busily digging in there, but the town was peremptorily stormed on the 23rd. This time Hopton claimed to have taken another 140 prisoners, but Ruthven and most of his men were taken off in small boats. Buoyed up by their altered fortunes the Royalists then proceeded to overstretch themselves again by making a second attempt to blockade Plymouth.

Once again they were hampered by the customary refusal of the Cornish Trained Bands to cross the Tamar. There was no alternative but to divide the army into a number of relatively small detachments and quite inevitably, on 21 February, Ruthven sallied out and fell upon Sir Nicholas Slanning’s post at Modbury. The Cavaliers at first put up a creditable resistance, but as soon as it grew dark, they fell back to Plympton leaving behind 100 dead, 150 prisoners and five guns. To make matters worse, it was learned that Stamford was pulling an army together at Kingsbridge, so next day Hopton mustered his forces on Roborough Down and then retired to Tavistock.

On the 28th he, Ruthven and Stamford agreed a local ceasefire. Bitter experience had shown that neither side was strong enough to invade the territory of the other so it seemed sensible to call a halt to unnecessary raiding during what remained of the winter. What was perhaps more surprising was that the ceasefire actually held for the stipulated forty days and nights.