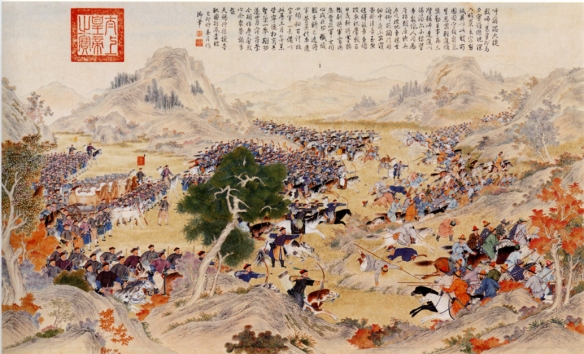

Battle of Qurman, 1759. General Fu De, on it’s way to relieve the siege of Khorgos was suddenly attacked by an enemy force of 5000 Muslim cavalry and with less than 600 men Fu De defeated the Muslims.

Soldiers of the blue banner parading in front of Emperor Qianlong.

nce the Three Feudatories Revolt had been crushed and Taiwan brought into the Qing realm, reforms were effected in the Qing military system. These reforms to the structure and organization of the Qing military established its essential form for almost two hundred years. The military system established by the Qing came closest to resolving the age-old Chinese concern—how to maintain an effective military force, yet insure that it could not threaten the ruling dynasty. The Qing military was successful in carrying out the imperial will, engaging in many large-scale military expeditions that added huge lands to the Qing empire. And yet, as important as the military was to the security of the empire, not until the twentieth century was the dynasty to be threatened again with military mutiny or revolt.

Bureaucratization

The Qing court learned much from its near disaster with the Three Feudatories Revolt. A trained, professional, disciplined military force was essential to the dynasty’s survival. It was only after the near debacle of the Three Feudatories Revolt that the Qing military became fully transformed from its origins as a traditional steppe-nomadic type of fighting force to one much more professional, and that administration of all the various military branches of the Qing was brought under central control.

Qing military forces were divided into two major branches. First, the Eight Banners resumed their role as the main strike force of the dynasty, and a central banner office was maintained at the imperial palace. To ensure their military effectiveness, the civil functions of the Qing Eight Banners were drastically reduced. Second was what was called the Green Standard Army. Originally composed of surrendered Ming armies, this was the main force that had defeated Wu Sangui’s rebels. After the rebellion, this army too was completely bureaucratized and administered by the Board of War.

At the top of the whole military apparatus, and very much in control, was the emperor. By the early eighteenth century the emperor was advised on military matters by a new office called the Grand Council. Much like a general staff, the Grand Council advised the emperor on military affairs and planned, organized, and oversaw campaigns. However, commanders of garrisons and major expeditions answered directly to the emperor, not the Grand Council. This body was advisory only, although at times individual Grand Councilors were assigned to lead expeditions.

Reorganization of the Eight Banners

The poor performance of the Eight Banners during the early years of the Three Feudatories Revolt led to major changes in the institution. The Qing leadership determined that too many bannermen had been used in civil functions, taking many of the most effective soldiers away from military duties. As Manchu control of China became more secure during the course of the Three Feudatories Revolt, banner officers were returned to their units and training and discipline emphasized. From this time it was rare that middle- or lower-ranking banner officers were used in civil functions. Some banner generals were placed in top civil positions throughout the rest of the dynasty, but often the banner designation of these officials was more social than functional. In other words, these were Manchu “generals” who only served civil functions, never leading troops in direct combat.

Militarily, by the early eighteenth century there had developed a core of competent, veteran Manchu (and some Chinese) high-ranking officers who were called on to lead military expeditions or serve as subordinate commanders or staff to the leaders of expeditions. There was constant replenishment of this key leadership group throughout the eighteenth century, with most beginning their careers as small unit leaders and rising through the ranks as they distinguished themselves in combat. Most of those who reached the very top military ranks were related to the imperial family through blood or marriage.

Membership in the banner military force was hereditary, although all officer positions were filled through appointment by the emperor. It was quite common for a banner soldier who distinguished himself in combat to be promoted to the officer ranks. There were even a few cases of these commoners rising to some of the senior banner positions.

The garrison system of the Eight Banners reflected their dual role as defenders of the dynasty’s position and the main military arm of the imperial court. Over half of the banner force was placed in garrisons near the capital or in Manchuria, the Qing homeland. The rest of the banner force was posted in garrisons located in or near key cities throughout the rest of China, and at strategic points along key waterways, such as the Yangzi River and Grand Canal. To reinforce the elite nature of the bannermen and to keep them from becoming too tied to local areas, garrisons were kept in segregated walled compounds and rotated with the capital garrisons from time to time. Also, only banner officers could take their families along with them to provincial garrisons. Even in the mid-eighteenth century, however, this regulation was often ignored.

Over time the banners underwent significant internal changes as well. As the number of bannermen swelled due to population increase, many Chinese and Mongol banner units were reclassified as civilians or placed in the Green Standard Army. So while in 1700 a majority of bannermen were Chinese, by 1800 the large majority were Manchu. Also, the banners reflected the changing nature of warfare. Originally an almost all-cavalry force, by the mid-1700s the large majority of bannermen were infantrymen equipped with firearms. Most banner cavalry units were maintained in Manchuria or the capital region. Also, the Mongol banners by this time were almost solely cavalry units.

Green Standard Army

During the later years of the campaigns to defeat the Three Feudatories, the Qing court came to rely increasingly on Chinese units, called the Green Standard Army. This military force, which numbered over 600,000 during most of the eighteenth century, had by 1700 come to serve primarily as a constabulary force, designed to maintain local law and order and quell small-scale disturbances, but also contributing the bulk of forces dispatched in major campaigns. The Green Standard Army was extremely fragmented, with literally thousands of large and small outposts throughout the empire, many with as few as twelve men. During peacetime it was rare for one officer to command more than 5,000 men.

The Board of War, based in the Imperial City and directly under the control of the emperor, administered the Green Standard Army. The board did not have operational control over the soldiers of the Green Standard Army, even those few posted to the capital region, but it dealt with issues such as recruitment, pay and provisions, promotion, and rewards and punishment.

Operational control of the Green Standard Army was on the surface very complicated. There was no general-in-chief based at the capital, and in fact no officer higher than the provincial commander-in-chief (tidu). Provincial garrison units involved in operations outside their province came under the control of the emperor and any officials he had designated, rather than the provincial commander-in-chief. However, even within a province the provincial commander-in-chief, nominally responsible for all Green Standard troops in the province, had direct control of no more than 5,000 men. Provincial governors had their own contingents of about 5,000 men, and several other garrisons were commanded by officers who answered directly to the governor-general (an official above the governor who normally oversaw two or more provinces). Most of the rest of the provincial Green Standard force answered to one of several brigade generals scattered throughout the province. These brigade generals usually had both administrative and operational control over their men, but only within strictly defined territories. The provincial tidu had command authority over most of the brigade generals, except those commanding garrisons located at strategic spots, such as along the Grand Canal or next to major port cities (such as Shanghai or Guangzhou). The tidu also had the right to engage in direct communications with the emperor and the Grand Council.

Strictly speaking, the Green Standard Army was not a hereditary force, although the dynasty directed its recruiting efforts primarily at sons and other relatives of serving soldiers. Enlistment was considered a lifetime occupation, but it was generally very simple to be reclassified as a civilian. During emergencies (usually in regions engaged in ongoing combat operations) conscription might be resorted to, but the Qing preferred to utilize local militia forces to augment its regulars. Militiamen—and sometimes whole militia units—who had distinguished themselves in combat were often incorporated into the regular Green Standard Army.

Green Standard officer ranks were filled in three main ways: (1) from the Eight Banners (officers who, although serving in the Green Standard Army, received pay and evaluations through the banner office), (2) through promotion from the ranks after a soldier had distinguished himself in battle (though this was much more common within the banners than in the Green Standard Army), and (3) by means of the military examination system. The military examinations had much less prestige than the civil service examinations, and were considered much less rigorous. Examinees were evaluated on their knowledge of the traditional Chinese military classics (especially Sunzi’s Art of War), as well as tests of physical strength and endurance: horseback riding, archery, and lifting heavy rocks. Surprisingly, there was no test of handgun marksmanship, despite the fact that the Green Standard Army relied heavily on firearms by 1700. The obsolete nature of the military examination did not come under serious criticism until well into the nineteenth century, after defeats at the hands of the European powers.

There was also a small Green Standard Army naval component, but this was never large and was designed mainly to suppress pirates. There were numerous patrol craft armed with small cannons, and combatants were all regular Green Standard soldiers. This force was fairly effective in keeping the peace along the main waterways, but very poor at coastal security. Faced with large pirate gangs, the court often preferred to incorporate the pirates into the Qing navy rather than fight them. The pitiful state of the Qing navy can be attributed to the fact that from the conquest of Taiwan in 1683 until the mid-nineteenth century, China was not faced with any serious threats from the sea.

Except for some of the elite Manchu cavalry forces, who relied primarily on mounted archery, almost all of the bannermen and Green Standard Army soldiers were armed with matchlocks. Each major garrison produced its own weapons, although there were also some large production facilities in the capital. The matchlock remained essentially unchanged for nearly two hundred years, but until serious confrontation with Western powers in the nineteenth century it was still at least equal, and often superior, to the weapons possessed by the Qing’s adversaries.