Following the sack of Thebes, the departing Assyrian army had left the city’s mayor, Montuemhat, in control of the south. A close relative of Harwa’s and an equally dominant presence, Montuemhat had been a loyal servant of the Kushite Dynasty and was even married to a Kushite princess. In the heyday of Taharqo’s reign, none of this had done his career any harm, but it had latterly become something of an embarrassment. However, Montuemhat was a master at bending with the political wind. To strengthen his already considerable local support, he devoted himself to restoring the depradations of the Assyrian army, repairing temples and carrying out extensive building works to return the city’s monuments to their former glory. Not least among these was his own tomb, itself the size of an average temple. When it came to the final stages of its decoration, Montuemhat decided, diplomatically, to show his Kushite wife not as a Nubian princess but as the epitome of native Egyptian femininity—just in case his new political masters should suspect him of divided loyalties. It was through such maneuverings that he remained the effective ruler of Upper Egypt, from Khmun to Abu, under three different regimes, Kushite, Assyrian, and finally Saite.

In keeping with such masterful fence-sitting, official Theban documents continued to recognize the moribund Kushite Dynasty for the first eight years of Psamtek’s rule. The daughters of the two greatest Nubian kings, Piankhi and Taharqo, still occupied two of the most senior positions in the city’s religious hierarchy, god’s wife of Amun and “divine adoratrix of Amun,” respectively. In the face of such grandeur and tradition, a Libyan princeling from the western delta could hardly compete. Psamtek knew that effective mastery of the south depended upon control of the Amun priesthood. He had an answer to that, too.

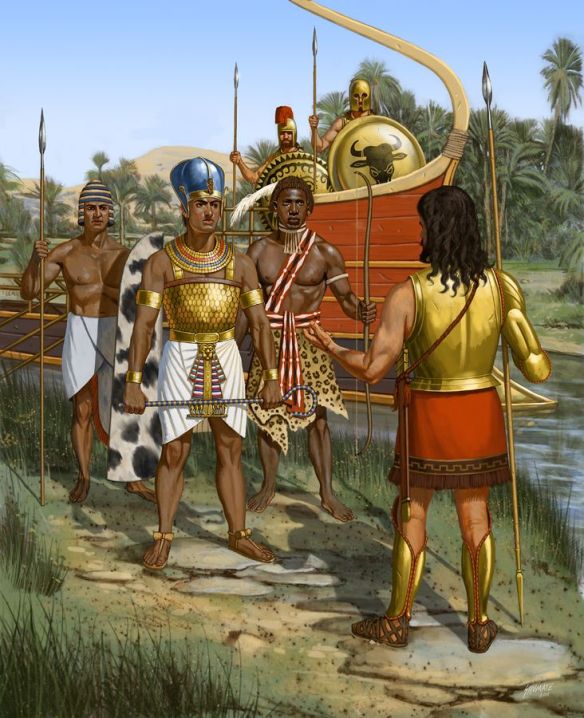

On March 2, 656, a magnificent flotilla of ships set out from the quayside in Memphis, bound for Thebes. There were tenders, supply ships, and, at the center of the fleet, a royal barque, shimmering with gold leaf in the bright spring sunshine. In overall charge of the six-hundred-mile expedition was the prince of Herakleopolis and chief harbormaster of Egypt, Sematawytefnakht, Psamtek’s relative by marriage and a close confidant. He had been given the responsibility for planning the journey and requisitioning supplies from all the provincial governors through whose domains the flotilla would sail. As with the Following of Horus at the dawn of Egyptian history, this program achieved the dual purpose of sparing the royal exchequer the burden of such a costly undertaking while giving Psamtek’s local subordinates the opportunity to outdo one another in demonstrating their loyalty. Among the many exotic provisions under Sematawytefnakht’s command, there was one particularly precious cargo: Psamtek’s young daughter, Princess Nitiqret. For she was leaving the royal residence to follow a destiny mapped out for her by her father: she was about to be formally adopted as heiress to the god’s wife of Amun.

After sixteen days’ sailing, the flotilla arrived at its destination and moored at Thebes. Crowds of people lined the riverbank to see the princess come ashore. Before she had a chance to take in her strange new surroundings, she was whisked off by waiting officials to the great temple of Amun-Ra at Ipetsut, to be welcomed by the god’s oracle. The formalities completed, Nitiqret was introduced to Shepenwepet II and Amenirdis II. How strange these two dark-skinned African women must have seemed to the delta princess! Yet they were about to become her legal guardians. Psamtek had taken a long-term view. Rather than forcibly ejecting the incumbent god’s wife and her designated heir and risk alienating Thebes, he had negotiated the adoption of his own daughter as their eventual successor. This set the seal on his reunification of Egypt and guaranteed that a Saite would eventually succeed to the most important religious office in the south. It was a diplomatic masterstroke.

And an economic triumph. At the heart of the legal agreement, which was drawn up in writing to ensure there could be no backsliding by the Theban authorities, financial concerns loomed large. The contract assigned to Nitiqret (that is, to her father) all the property of the god’s wife “in countryside and town.” She would receive daily and monthly supplies from the most powerful Theban officials, obligations from which they could not shirk. Heading the list of donors was Montuemhat, who promised to provide bread, milk, cakes, and herbs every day, together with three oxen and five geese per month—all in all, a considerable commitment. Joining him as donors were his (Kushite) wife and eldest son; their loyalty to the new dynasty was thus affirmed. The historic Ipetsut gathering of 656 brought together representatives of all the principal powers in Egypt’s recent past. Montuemhat was the last great figure of the old Theban hierarchy. Shepenwepet and Amenirdis, together with the high priest of Amun Harkhebi (Shabaqo’s grandson), stood for the old Kushite Dynasty. Sematawytefnakht embodied the altered dispensation in the north; while the young girl at the center of it all, Princess Nitiqret, represented Egypt’s new Saite masters. The ceremony was nothing less than a changing of the guard.

To reinforce his newfound authority in Upper Egypt, Psamtek dispatched one of his best generals to Thebes. His mission was to keep a lid on any potential dissent, establish a new garrison at Abu, and maintain a close eye on developments in Nubia. Diplomacy backed by force was the Saite way, and the new dynasty had no intention of allowing Tanutamun, his heirs, or his supporters to stir up renewed trouble in the south.

Yet the proud Kushites were not so easily tamed. After Tanutamun’s death in 653, new generations of Nubian rulers looked northward again with greedy eyes. As they rebuilt their forces and perfected their strategy, they waited for the moment to recapture their lost northern kingdom. After a long and patient interval, an opportunity finally presented itself in 593. Psamtek’s grandson and namesake, Psamtek II (595–589), had only recently ascended the Egyptian throne and seemed preoccupied with political developments in the Near East. The Kushites assembled their entire army in lower Nubia and prepared to strike. It was a profound miscalculation. Psamtek II differed from his grandfather in one crucial respect: he had neither the need nor the inclination to pander to Kushite pretensions. Upper Egypt had been firmly within the Saite sphere for half a century. Nitiqret had finally succeeded as god’s wife, and all the other important posts in the Theban administration had been given to Lower Egyptian loyalists. The Nile Valley was properly unified under central control for the first time in nearly five hundred years. No Kushite army was going to change that.

Warned of the impending invasion, Psamtek II did not hesitate, sending his own expeditionary force southward to Nubia, and accompanying it himself as far as Abu. Ionian, Carian, and Judaean mercenaries led the charge, pausing only at the temple of Abu Simbel to carve their names on the legs of Ramesses II’s colossi. On they pressed, razing the town of Pnubs (founded on the site of the ancient Kushite capital, Kerma) in an orgy of savagery worthy of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Walking among the Nubian dead, Psamtek’s troops are said to have “waded in their blood as though in water.” The army did not stop until it had reached Napata, where it sacked and burned the royal palace and smashed the kings’ statues in a symbolic act of vengeance against the Kushite Dynasty. Back home in Egypt, Psamtek II ordered the names of the Nubian pharaohs—Piankhi, Shabaqo, and their successors down to Tanutamun—to be erased from all monuments, even private statues. The aim, through might and magic, was to wipe the Kushites from the pages of Egyptian history. After 135 years of mutual hostility between the Saite and Kushite dynasties, with the Nubians having had the upper hand for more than half that time, revenge was sweet indeed.

A TANGLED WEB

It was not in the Assyrians’ character to let a hard-won province secede. Having launched two invasions to secure Egypt’s dominion , Ashurbanipal must have been galled at the Saite expansion. Yet Psamtek I had broken free from Assyrian control with barely a twitch from Nineveh. The reason was a preoccupation closer to home. In southern Mesopotamia, right under the Assyrians’ noses, their old rival Babylonia was in the ascendant once again. Within months of Ashurbanipal’s death, a vigorous new king came to the throne in Babylonia and set about recapturing the lands lost to Assyria two generations earlier. Assyria decided to swallow its imperial pride and make common cause with its erstwhile vassal, Saite Egypt, in united opposition to this new threat.

At first, the policy was a spectacular success. Psamtek I came to Assyria’s support in the Near East, campaigning against Babylonian expansion all the way to Carchemish, on the banks of the Euphrates—the first time an Egyptian army had gone that far since the days of Ramesses II. Babylonia seemed to have been stopped in its tracks. But the tide of history was running against an overstretched Assyrian Empire. Despite Egyptian assistance, Assyria was heavily defeated by the Babylonians in 609 and forcibly absorbed into Babylonia a year later. Now fighting in self-defense, an Egyptian army returned to Carchemish in 605 and launched a spirited attack against a Babylonian force, but was thoroughly routed. Egypt lost its remaining footholds in the Near East and saw its allies fall to Babylonia’s sword. First Tyre, and then Jerusalem—one by one, the pharaoh’s friends were swept aside by the sheer might of the Babylonian military machine. By 586, despite a number of brave rebellions, the independent states of Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine had been wiped from the map. Judah was enslaved and the Jews deported to Babylon, there to bewail their exile.

Egypt was now the front line. Psamtek II’s son and successor, Wahibra (589–570), successfully repulsed an attempted Babylonian invasion in 582, but knew very well that he would need allies to safeguard Egyptian independence. Following his father’s example, he looked to the Greek world, and appointed Ionian and Carian mercenaries to positions of prominence in the Egyptian army. They had served with distinction under Psamtek I and II, and might do so again in the cause of freedom. It was a necessary strategy, given the circumstances, but proved deeply unpopular with the native Egyptian military, who felt increasingly marginalized by the high-ranking foreigners in their midst. For the generals, the last straw came in January 570 when a disastrous campaign in Libya led to a full-scale mutiny by the surviving Egyptian forces. Wahibra sent one of his most experienced commanders, Ahmose, to put down the revolt. But far from reimposing order, Ahmose promptly seized power and was proclaimed king by the rebels. Turning back toward Egypt, he and the renegade army marched on the dynastic seat of Sais, seized it, and forced Wahibra to retreat to his heavily fortified palace in Memphis. By August, the general had been recognized as pharaoh, a second Ahmose, throughout the western delta. In October, after a lengthy standoff during the hot summer months, Wahibra attempted to regain his throne by marching on Sais. Ahmose’s army met him head-on and comprehensively defeated the loyalist forces. Wahibra escaped with his life and fled abroad … to the court of Babylon. The Babylonian king, Nebuchadrezzar, could scarcely believe his luck. Here was an unmissable opportunity to meddle in Egypt’s internal affairs and put a Babylonian puppet on the throne of Horus.

Realizing the impending danger, Ahmose II (570–526) took immediate measures to guard against an invasion. He concluded an alliance with the Greeks of Cyrene, on the North African coast of Libya (founded by colonists in the seventh century), while removing a Greek garrison in the eastern delta thought to harbor sympathies for Wahibra. Pragmatism, not ideology, was the order of the day. In 567, a Babylonian force led by the deposed king attempted to invade Egypt by land and sea, but was roundly defeated. This time, there was no escape for Wahibra. He was captured and killed. Despite the ignominy of his final years, he was nonetheless buried with full royal honors by a victorious Ahmose. The new pharaoh had his finger firmly on the pulse of popular opinion and, although he was happy to be portrayed in satirical texts as “one of the boys” (no doubt to retain the support of the native military), he took pains in public to position himself as a pious and legitimate ruler.

If the army rebels who had put Ahmose II on the throne had been hoping for a reversal of Egypt’s recent philhellenic tendencies, they were to be frustrated. As part of his staunchly anti-Babylonian foreign policy, Ahmose actively curried favor with the Greek city-states. In the aftermath of the Sea Peoples’ ravages, Greece had been resettled during the ninth century and was now dominated by a series of independent cities that were actively extending their influence by establishing colonies around the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts. Greek wealth depended above all on free trade, and the city-states were no fans of a Babylonian kingdom whose expansionary ambitions threatened their prosperity. Besides this political alliance, Egypt also had a military interest in the Greek world, for the Aegean mercenaries were famed and prized in equal measure throughout the Near East. The pharaoh made generous donations to Greek shrines (he paid handsomely toward the rebuilding of Delphi after it was gutted by fire) and even married a Greek princess. But his flagship initiative was directed at the Greek traders in Egypt. Ever since the reign of Psamtek I, settlers from the Ionian coast had made their home in the delta. Mercenaries had become entrepreneurs, and many had grown rich from the import-export business, bringing olive oil, wine, and, above all, silver from the Greek world and sending Egyptian grain back in return. It was far too lucrative a business for the Egyptian government not to take an interest, and Ahmose II wanted a share of the profits. Under the guise of granting the Greeks a free trade zone, he passed a law limiting their mercantile operations to the town of Naukratis—conveniently situated just ten miles from Ahmose’s royal residence at Sais. This allowed him to regulate and profit from international trade, while posing as its enlightened sponsor.

With royal patronage and protected status, Naukratis swiftly became the busiest port in Egypt. It also developed into an extraordinary cosmopolitan city, where Cypriots and Phoenicians rubbed shoulders with Milesians, Samians, and Chians. Several Greek communities had their own temples—the Chians reverenced Aphrodite, while the Samians preferred Hera—and there was even an ecumenical “Hellenion,” where the different communities could come together to worship “the gods of the Greeks.” But alongside all this piety, there was also a seamier side to life. Naukratis developed a reputation throughout the Greek world for the attractiveness and looseness of its women. As Herodotus remarked, it was “a good place for beautiful prostitutes.” One particularly notorious courtesan had her freedom bought by the brother of the poet Sappho; he no doubt had mixed motives for her emancipation.

By the middle of the sixth century, under Ahmose’s wise and wily rule, Egypt was experiencing a minor renaissance. Prosperous and stable at home, respected and valued abroad, it could claim, once again, to be a leading power. In the space of a century it had seen off first the Assyrians, then the Babylonians, and had won its spurs as a key player in the tangled web of international relations. It was also a changed country, more multiethnic and multicultural than in the past. But the Nile Valley had always been a melting pot and a magnet for immigrants, and had successfully absorbed them all. In the end, pharaonic civilization had always emerged stronger, triumphant. For the gods had ordained it, and it would always be the case—or so the Egyptians naively believed.