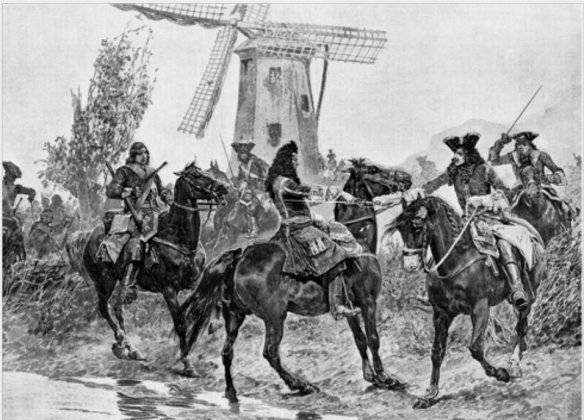

The surrender of Tallard on the banks of the Danube.

The Spoils of Victory

For all that hot August day the two armies had been in close and deadly combat, and there was no doubting that the day had been a brutally stiff test for all concerned. One army had been beaten and had broken and fled, while the other stood triumphant but exhausted. With the coming of nightfall, Marlborough caught a few hours’ sleep in a mill on the edge of Höchstädt that had served the French as a gunpowder store before the battle. Much of the powder was still lying strewn around, but no accident occurred to disturb the Duke’s rest. The morning after the battle Marlborough and Prince Eugene made their way to the quarters in Höchstädt that had been hastily allotted to Tallard and his fellow captive generals, and courteously asked after their welfare. The marshal, who was nursing a wounded hand, requested that his own coach be sent for, and Marlborough, sensitive to the very natural sense of dejection in his beaten opponent, agreed to do so. Marshal Marsin and the Elector of Bavaria, meanwhile, continued their withdrawal westwards, and got their own troops and those remnants of Tallard’s army that had escaped, across the Danube at Lauingen, and put that watery obstacle between themselves and any immediate pursuit as they made their dejected way towards Ulm. A rearguard was prudently left to burn the bridge if the allies approached.

So much had been achieved, but the cost of the victory was heavy, with Marlborough’s wing of the army losing some 9,000 killed and wounded, and that of Eugene 5,000, out of the total of 52,000 deployed on the field of battle; more than one in four of those who had made their way through the defile at Schwenningen had fallen. The losses of the French and Bavarians were even more astonishing, and starkly illustrated the scale of their defeat, amounting to 34,000 (including a staggering tally of nearly 14,000 unwounded prisoners). This figure indicates total tactical defeat. The disaster that had occurred to Tallard’s army in the debacle of Blindheim village was further illustrated by the fact that 12,149 of these prisoners were French, while no fewer than forty-two senior and general officers were now captives of the Allies, a sure enough sign of the collapse of their army. John Millner, who fought on the Plain of Höchstädt that day, wrote that the senior prisoners taken were:

Count Tallard, four lieutenant-generals, six major-generals, eight brigadier-generals, three colonels of Horse, three colonels of dragoons, thirteen colonels of Foot, most of them counts, marquises, princes, dukes and barons, besides three Marquises and one captain of the Gens d’Armes.

In a typically generous and compassionate gesture, Marlborough allowed the captive French officers to keep and wear their swords and they were to be treated well, but inevitably the rank and file got rather rougher handling from their victors, and many were stripped of their possessions and occasionally even their clothing.

Among the booty that fell into allied hands were 100 pieces of artillery and mortars, 129 infantry colours and 110 cavalry standards, 5,400 wagons and coaches, 7,000 horses, oxen and mules, the French pontoon train, eight caskets of silver, 3,600 tents and hundreds of sutlers and other camp followers, including some rather exotically dressed ‘ladies’. A huge amount of other camp stores, forage, ammunition, food and campaign equipment was taken, and so great was the haul that it could not be counted and gathered in; much had to be left to be pillaged or rot where it lay. The large numbers of prisoners posed an immediate practical problem for the victors, as they had to be guarded, housed (after a fashion) and fed. ‘We know not how to dispose of them,’ Adam Cardonnel wrote to a friend. ‘If we could get well rid of these gentlemen I hope we might soon make an end of the campaign.’ Most of those taken captive had fallen to Marlborough’s attack, but the duke saw to it that Eugene was allotted a fair share as a part of the spoils of their joint success. Many of these men subsequently volunteered to take service with the imperial army, rather than having to labour in the mines of Austria which was the stark alternative offered.

The war plans of Louis XIV were now in ruins – the Court at Versailles had been enjoying a grandly staged masque, ironically enough intended to celebrate the victory of the River Seine over all the other rivers of Europe, when, Duc de St Simon wrote:

The King received the cruel news of this battle, on the 21 August, by a courier from the Marshal Villeroi. The entire army of Tallard was killed or taken prisoner, it was not known what had become of Tallard himself. Neither the King or anyone could understand, from what reached them, how it was that an entire army had been placed inside a village, and had then surrendered. What was the distress of the King, we were not accustomed to such misfortune.

So great was the shock when the sheer scale of the defeat was confirmed, that some thought that the King had suffered a stroke. A member of the Gens d’Armes, who had been so decisively and repeatedly repulsed that day of battle, wrote in an attempt at explanation of their conduct: ‘I charged three times with my brigade [but] I did not see a general officer during the whole battle.’ The comment has, of course, to be treated as self-serving and with some caution. John Millner had commented that three French general officers had been killed or mortally wounded on the field, these being the gallant cavalry commander von Zurlauben, the Marquis de Blainville (the son of the great naval reformer, Colbert), and the Marquis de Clerambault, of unfortunate memory.

The French effort to drive Austria out of the war had failed dramatically, and the loss of one of Louis XIV’s main field armies could not easily be made good, despite the deep resources of France and that of the King and his people. The military prestige of France that had been so long in the making, was badly damaged, and the Elector of Bavaria, one of the King’s main allies, was ruined and became almost a fugitive, while other allies and adherents would not be at all encouraged by this awful turn of events. At another important level, French field commanders, whether or not they had been present in southern Germany that fateful summer, had a grim lesson served to them – the Duke of Marlborough with his ambitious schemes, and the men he led, were dangerous opponents.

The Pursuit

Meanwhile, on the Danube, the allied army, understandably flushed with victory but battered and weary after such efforts, had rested while the wounded were sent to Donauwörth and then on to hospitals in Nördlingen. They only began their pursuit of their beaten opponents on 18 August, but so depleted were some allied regiments, that they could attempt little more without replenishment, and the march was less vigorous than might have been hoped for. The Comte de Merode-Westerloo remembering that: ‘If the foe had been quick enough, not one of us would have escaped’. Still, the city of Augsburg was given up shortly after the battle, as were the garrison towns of Memmingen and Biberach, with more stocks of supplies falling into allied hands, and the Margrave of Baden took possession of Ingolstadt – he had missed the day of glory at Blenheim, and regretted the fact, but the fortress was still worth having. The Margrave was summoned to join in the pursuit, but he had forty miles to make up yet, and would not be on the scene with fresh troops for some time.

For their opponents, there could be no early hope of recovery from such a defeat. The French and Bavarians had left Ulm by 21 August other than a small garrison left as a delaying tactic, and abandoning in the process much of their remaining baggage to enable them to make better speed as they withdrew towards the passes of the Black Forest and the Rhine. The allies pushed forward as best they could given the state of the army, while congratulations for the Duke and Eugene on their achievement poured in from many quarters.

The morale of the shocked French and their Bavarian allies was, understandably, badly dented and desertions from the Elector’s regiments were numerous, further weakening his ability to continue to campaign as an ally of France with anything like proper effect. The French commander in Alsace, Marshal Villeroi, had come forward to Villingen on 23 August to assist in the withdrawal, an operation he handled very well. Marsin and the Elector managed to get most of their remaining forces, reduced now to a mere 12,000 strong after casualties and desertions, back across the shelter of the Rhine at Strasbourg by the end of August. Having pushed their march in four columns on parallel roads, Marlborough and Eugene came together at Philippsburg on 5 September, and passed an advanced detachment of troops over the Rhine the next day to occupy a strong position at Speyerbach without any opposition. The Margrave of Baden arrived with his cavalry three days later, and the allied concentration of forces was complete once more. Their next move was anxiously awaited by the French, but a fresh approach to the Elector of Bavaria proposing that he abandon his alliance with France went unheeded, even though it would have restored him to his position.

A plan formed by Marlborough to thrust forward to the Moselle valley was thought to be too risky until the army had been fully replenished, and so a siege was to be laid to the French-held fortress of Landau. Baden, typically, was reluctant to take risks, and in this he was probably right, as the forces of Marlborough and Eugene were still well under-strength – much had been achieved but nothing was to be rashly thrown away. Villeroi was also prudently cautious, and could get only modest assistance from Marshal Marsin, so he gave ground at a measured pace, holding the line of the River Quieche until 9 September, and then falling back to a new position at Langencandel, ‘Famous for being a strong post,’ Marlborough wrote, ‘it being covered with thick woods and marshy grounds.’

As the allies advanced, Villeroi withdrew across the river Lauter and then to a position at Hagenau, and the siege of Landau could begin. Ulm had capitulated to Baron Thungen on 11 September and his 14,000 troops were marching to augment the allied army in Alsace. However, the Imperial troops under Baden made slow work of the siege of Landau, where the French garrison, under command of the Marquis de Laubanie, put up a valiant resistance, and the autumn weather turned foul. The fortress did not capitulate until 23 November. Marlborough, meanwhile, had set off with a 12,000 strong detachment of troops in the pay of Queen Anne, across the broken country of the Hornberg to seize Trier on the Moselle river at the end of October, and went on to lay siege to the fortress of Trarbach. Veldt-Marshal Overkirk had marched south with a corps of Dutch troops to meet the Duke, after the triumph at Blenheim no summons would go unanswered while the French were in such disarray. Marlborough left the siege operations to Overkirk and the Prince of Hesse-Cassell, and returned to oversee the siege at Landau, where matters had gone on at a frustratingly measured pace but the fortress at last capitulated on 23 November. The allies had firmly established themselves in Alsace, and the French defensive line on the Rhine was breached, while a base had also been gained in the Moselle valley ready for the resumption of campaigning in 1705. As such, the initiative in the War for the Spanish throne had firmly passed from the French to the Grand Alliance.