Catiline’s Conspiracy

While Pompey was in the East, Italy was shaken by the conspiracy and armed insurrection of Catiline (Lucius Sergius Catilina). The relevant facts have reached us almost entirely through Sallust and Cicero. Sallust was anything but politically unbiased, and Cicero, as the man whom Catiline conspired to murder, and who ordered the execution of Catiline’s accomplices, was obviously not impartial.

Catiline had been involved in an earlier plot to overthrow the constitution and seize power in 65 BC. He was influential and well connected and on this occasion there had been no question of bringing any charge against him. His second plot, again the product of political disappointment and, we are encouraged to believe, sheer viciousness, was matured in 63 BC. The original plan was to coordinate widespread disturbances throughout Italy, with the main uprising concentrated in Etruria, where old soldiers who had become bankrupt farmers might be relied upon for support. When Cicero, as consul, obtained information of this plot, the conspirators held an emergency meeting at Rome in the Street of the Sickle-makers and adopted a more desperate programme. They resolved to murder Cicero next day, set Rome on fire, and incite the slave population to rebellion and looting. Meanwhile, their sympathizers in other parts of Italy were to take up arms without further delay and the insurgents of Etruria were to march on the terrorized city. Cicero, who was consistently well informed, received prompt warning of his danger and denounced Catiline to his face in the Senate – of which the accused was a member. After this, Catiline fled from Rome to join his army in Etruria.

Other conspirators, however, remained in Rome. Hoping to gain further supporters among the Gauls, they made contact with some envoys of a Gallic tribe then in the city. Cicero’s informants again served him well. Through the agency of the Gauls, he obtained signatures on incriminating documents and arrested five of the leading conspirators. Their fate was debated before the Senate. Caesar pleaded for life imprisonment. But Cicero was supported by Cato, the much-respected great-grandson of Cato the Censor, and ordered the execution of the conspirators without trial. His justification was the state of emergency which then existed, but not everyone considered him justified. Once the conspiracy at Rome had failed, Catiline’s mainly ill-armed forces in Etruria had little hope of success. Regular troops were sent against him. His line of retreat northward was cut off, and he was overwhelmed and killed in a battle at Pistoria.

Catiline’s blundering plot hardly amounted to a war, yet it had considerable military significance. Italy was the strategic centre of the Mediterranean world, but it was at the same time the most vulnerable area in that world. Ever fearful of military despotism, the Senate preferred to see Rome’s legions deployed in distant and overseas provinces, while Italy, comparatively denuded of troops, remained an attractive prey for any armed adventurer who could rally sufficient malcontents to his support. Catiline’s insurrection had its precedent in that of Lepidus in 77 BC. Lepidus’ attempt had been crushed with Pompey’s valuable aid. Catiline had timed his uprising to take place when Pompey was no longer at hand. That Pompey might return from the East, bringing retribution, as Sulla had done, was a possibility which the conspirators had been forced to take into account, and they had accordingly planned to seize Pompey’s children as hostages. Apart from that, any military régime which could control Italy possessed the advantage of interior communications, the importance of which remained to be demonstrated in later Roman history. It is hard to see how Catiline could have hoped ultimately to make himself despot of Rome. We do not know precisely what his plans and intentions were. But he certainly could have created great havoc before being subdued, if it had not been for Cicero’s highly efficient “secret service”.

The Parthians

In the course of their eastern wars, the Romans had several times come into contact with the Parthians. Sulla, reaching the Euphrates, had negotiated with them on friendly terms. Lucullus, distrusting them as allies, had prepared to attack them. Pompey, invoking their aid, had promised them Armenian frontier territory, but failed to keep his promise after Tigranes’ humble submission. Like other Asiatic kingdoms, Parthia was a succession state of the Seleucid Empire, the Parthian leader Arsaces having founded an independent dynasty in the middle of the third century BC. With this Arsacid dynasty the Romans had to deal.

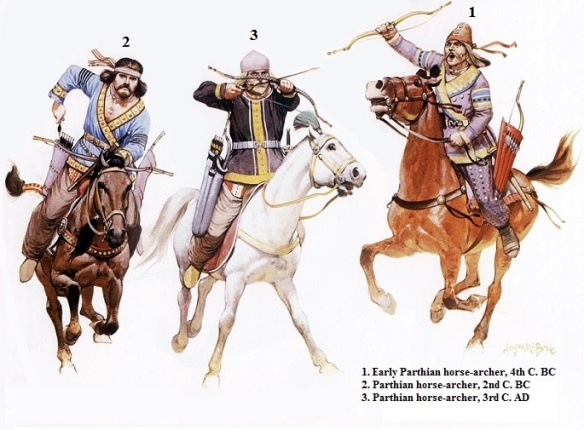

The culture of the Parthians was in many ways a characteristic legacy of Alexander’s eastern conquests: a discrepant and sometimes grotesque blend of Greek and barbaric traditions. But their way of warfare owed little to Macedonian precedents. There was no clumsy imitation of the phalanx, such as Mithridates had used. The Parthian army was a cavalry army, and its cavalry was of two kinds. The nobility, not unlike medieval knights, were lancers, protected by coats of chain mail and mounted on strong horses that were also mail-clad. These heavy cavalrymen are referred to by Greek writers as cataphractoi. The word literally means “covered over”. But the more typical Parthian warrior was a mounted bowman who wore no armour and, relying on his mobility, rode swiftly within arrowshot of the enemy to let fly a deadly shaft as he wheeled his horse and made off. The modern expression “a Parthian shot” is a reminder of this highly skilful manoeuvre. Given an Asiatic terrain of undulating hills or dunes and skylines that could conceal without impeding such horsemen, Parthian tactics were a formidable threat to a less mobile enemy. In addition, it should be noted, their bows were strong and their arrows penetrating, being capable of nailing a shield to the arm that supported it or a foot to the ground.

Before conflicting with the Parthians, the Romans had some experience of cataphracts. Tigranes’ army had included 17,000 heavily mailed horsemen. Lucullus, observing that these had no offensive weapons save their lances and were hampered by the weight and stiffness of their armour, had ordered his Thracian and Galatian cavalry to beat down the lances with their swords and attack at arm’s length. Similarly, he had instructed the legionaries not to waste time hurling their javelins, but to close with the enemy at swordpoint, attacking the legs of the armoured riders and hamstringing their horses; for their mail did not cover them below the waist. The purpose of coming to grips quickly was also to prevent the enemy from using his archers. In the mountainous country of Armenia, the tactics of the Parthian horse-bowman would in any case have been impossible.

The Parthians were masters of ruse, adepts in feigned retreats and ambushes. Their country was remote and, to the Romans at any rate, little known, and they were in a position to plant spies and false information on an invader who necessarily made use of local guides. They rallied their troops not with military trumpets but with an ominous and disconcerting roll of drums – perhaps like the beating of tom-toms. They would also wheel their galloping steeds close to the ranks of the enemy, raising dust clouds which had the effect of a smoke-screen. Their methods of warfare were utterly different from those which the Romans had encountered in Pontus and Armenia, and the discovery of this fact came as a great shock to the Romans.

The Disaster of Carrhae

The Romans were never able to subdue or dominate the Parthians, and their first campaign against this untried enemy, led by Marcus Crassus in 53 BC, ended in a major disaster near Carrhae in Mesopotamia. In his youth, Crassus had, like Pompey and Lucullus, seen military service under Sulla. He had grown rich at the expense of Sulla’s outlawed victims. The Social War and the operations against Spartacus had proved that he possessed real military ability but, throughout his long political career, money had been his chief weapon. Only the spectacle of Pompey’s success and, latterly, Caesar’s victorious campaigns in Gaul, had revived his ambition for military honour. As a result of a tripartite political agreement, in which Pompey and Caesar were his partners, he obtained Syria and Egypt as his province, seeing the opportunity for a prestigious war against Parthia.

Crassus launched hostilities without any authority from Rome and without any provocation from the Parthians, although a hostile atmosphere had been created by Pompey’s broken promises and the support given to a Parthian royal pretender by Pompey’s deputy in Syria. When Crassus occupied frontier cities in Mesopotamia, he was met by a challenging embassy from the Parthian king. Defiant language was used on both sides, and a state of war immediately existed.

Having based himself on Carrhae (Biblical Haran; modern Harran), Crassus with his army began to march on Seleucia, the old Babylonian capital of Alexander’s successor. The Roman legions very soon became a constant target for the enemy’s missiles, nor were their light-armed skirmishers numerous enough to ward off the attacks. Surena, the Parthian general, made sure that his bowmen were continuously supplied with ammunition, using an efficient camel corps to transport load upon load of arrows.

Crassus sent forward his son Publius with eight cohorts, 500 archers and some 1,300 cavalry. The Gauls, like Publius, had served with distinction under Caesar, and they had some success against the Parthian cataphracts, nimbly grasping the enemy’s long lances and stabbing the horses in their unprotected bellies from underneath. But in the end, Publius’ force, separated from the Roman main body, was annihilated, and the triumphant Parthians were able to taunt Crassus with the sight of his son’s head on a pike.

The Romans were now obliged to retreat by night, but they were by this time exhausted, and 4,000 wounded were abandoned to be butchered by the enemy. The Parthians were content to remain inactive during the hours of darkness, but gave chase again during the day, when the straggling Roman columns, as a result of their night march, had lost contact with each other. Crassus’ officer Gaius Cassius, better known to history for his action on the ides of March nine years later, led 10,000 men back to safety. Without more detailed information, we cannot confidently praise him for saving his men or blame him for deserting his general. Other officers, under pressure from the demoralized army, accompanied Crassus to a parley which Surena had proposed with obviously treacherous intent. In a contrived scuffle, the Roman negotiators were cut down; Crassus’ head was carried in triumph to the Parthian king, then concluding peace with the Armenians. In the whole campaign, the Romans are reported to have lost 20,000 killed and 10,000 prisoners. These last were settled by the Parthians as serfs in provinces farther east.

Despite the crushing defeat of Crassus, the Parthians made no attempt to follow up their victory. Unlike the Gauls or the Germans, they were under no pressure to migrate at the expense of other nations. Perhaps they also realized that the country into which Crassus had imprudently ventured was among their greatest military assets, and their way of fighting could not be equally successful on any other terrain. For many years, the Romans felt the disaster of Carrhae as a deep disgrace; apart from all else, their standards had fallen into enemy hands. But no sense of emergency was entailed. The Parthians did not even present a threat comparable with that which had been posed by Mithridates or the Cilician pirates.

Treachery apart, the Parthians were also indebted for their victory to the generalship of Surena – though what we hear of his character does not suggest the hardihood of a great military leader. When he travelled privately, Surena was accompanied by an enormous retinue, which included 200 waggons for his concubines. This made him look hypocritical when he expressed disgust at the pornography discovered in the baggage of the defeated Roman army. However, his personal ability is not in question. Indeed, his success excited the jealousy of the king whom he served, and soon after Carrhae he was put to death.