Military Command and Political Power

Sulla had tried to impose constitutional government by armed force. This attempt in itself was doomed to failure, for constitutional regimes depend upon a substantial element of consent and consensus among the population. In Sulla’s day, such an element was lacking, and the legislation by which he tried to make good the deficiency was in many ways anachronistic. He was perhaps justified in depriving the equites of rights and honours which Gaius Gracchus had conferred on them, but his laws reduced the People’s Assembly to a position which it had occupied in the years of struggle between Patricians and Plebs. He wished to guard the state against another Marius by reinforcing the old rules that had applied to consular elections. It was now required that magistracies should be filled by any one individual in strict order of ascent. A man could become consul only after first serving as quaestor, then as praetor, age qualifications secured that there would be a time interval between one appointment and the next. Re-election to the same office was a fortiori hampered by time regulations.

However, the new threat to the constitution came not from consuls and praetors, as Sulla had anticipated, but from proconsuls and propraetors. The exigencies of overseas wars had rendered the delegation of executive and administrative power inevitable. Distance, if nothing else, made it impossible to interrupt a war for the sake of an election, and the need for continuity of command was too obvious to be overlooked. Apart from that, the consuls were two in number, and the wide areas over which Rome now ruled could not be administered by a couple of magistrates, even allowing for their assistance by praetors. By contrast, constitutional precedent did not limit the number of pro-magistrates who could be appointed.

The first proconsul had held his office as an extension of his consular power in 326 BC. It had been an ad hoc measure to meet a military situation. Sulla had wished to limit the term for which pro-magistracies could be held to a single year, but the tasks which the pro-magistrates were called upon to perform often required a longer tenure of office. Pompey set a new precedent by having power conferred on him for a term of three years. Obstacles placed in the way of the consulate did not operate in the instance of special overseas commands. It was even possible for one who was not a magistrate at all to hold command in a province as a “private person” (privatus), and such commands were normally both military and civil in their scope. Admittedly, a proconsul’s power was limited to a certain area. But this area, as in the instance of Pompey’s command against the pirates in 67 BC, could be very large.

Sulla had provided that a consul should officiate for one year at home before being sent abroad with proconsular power. But in practice, it was possible for a consul in Rome to control foreign provinces through his senior officers (legati). Pompey, both on active service and while administering from a distance, made extensive use of legati. Originally, such officers, appointed to a general’s staff by the Senate, had been three or four in number. But Pompey in his campaign against the pirates made use of 24 legati. Both with proconsular responsibility for Spain from 55 BC and as consul in 52 BC he governed the province by proxy through the use of legati. But by this time, Sulla’s constitution had been completely eroded.

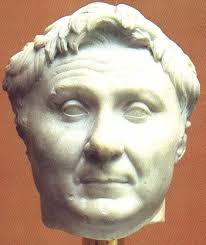

The delegation of authority, in one way or another, though expedient and formally constitutional, was a practice which hastened the downfall of the Republic. Nobody availed himself of this practice more than Pompey, and in many ways he was in the same paradoxical position as Sulla. He was, of course, a more amiable character and merely upheld, rather than imposed, a constitution by force.

The Early Career of Pompey

In 82 BC Pompey had himself been appointed as Sulla’s legatus first to Sicily then to North Africa, where leaders of the Popular party – who now had very little to lose – tried to rally resistance against the dictator and his establishment. In both theatres of war, Pompey had been wholly successful, and Sulla, whose concessions, no less than his ruthlessness, sometimes took men by surprise, permitted the junior general to celebrate a triumph.

The triumphal procession of a victorious general to the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, with his army, spoils and captives, attended by senators, magistrates and officials, sacrificial beasts, banners and admiring crowds, was granted under certain conditions. The commander of the Roman Popular forces in North Africa had allied himself with an African king, so that Pompey’s victory could be claimed to have taken place over a foreign power. But triumphs were the prerogative of consuls, praetors and dictators, and Pompey was not a magistrate of any kind. Nevertheless, Sulla, though an ardent constitutionalist, did not always justify his decisions on constitutional grounds. Nor were the celebrations in any way subdued. Pompey had, in fact, intended to have his triumphal chariot drawn by African elephants, but they were too big for the city gates and horses had to serve his turn.

After Sulla’s death another attempt was made to rally the Popular faction in Italy by men whom Pompey had himself raised to power. However, he showed himself at once a champion of the status quo, besieged the dissidents with their forces in Mutina (Modena), received their surrender and then executed them. Lepidus, the ringleader of the movement, fled to Sardinia and died there. Pompey’s military power and prestige now alarmed the Senate, and they were glad to post him to Spain, where Sertorius, another one-time supporter of the Popular party, had set up what amounted to an independent state.

Since the death of Gaius Marius, Quintus Sertorius was probably the only good general that the Popular party had possessed. When his partisans in Italy were menaced by Sulla, he seems to have realized that the single hope of resistance lay in adoption of an overseas base. He already knew Spain, having served there as quaestor, and in conflict with Celtiberian tribes had shown himself able to match the tribesmen in the employment of ruses and guerrilla tactics. In the years that followed Sulla’s return to power, Sertorius had repeatedly worsted Roman senatorial forces. He identified himself with local aspirations and came to figure rather as the leader of a Spanish nationalist cause than of any Roman political faction. Pompey had considerable difficulty in dealing with his Romano-Spanish guerrilla tactics and strategy, and might never have emerged victorious if treachery had not played its part. For Sertorius was murdered as the result of a conspiracy formed by his lieutenant Perpenna. Perpenna, however, was not such an adroit guerrilla fighter as Sertorius, and Pompey, laying a trap, soon captured him and put him to death.

In this early stage of his career, at least, Pompey resembled Sulla in his good luck. During his five years’ absence in Spain, Italy had been terrorized by a massive slave revolt. The slaves had defeated several Roman armies, but had at last been crushed by Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Sulla’s old officers, now an ambitious politician and general. Even so, 5,000 survivors of Crassus’ victory managed to escape and retreat northward into Etruria, where Pompey, returning from Spain with his legions, met and destroyed them. He did not hesitate to claim major credit for this successful operation, a claim which hardly improved his relations with the influential Crassus. Although Pompey had no unconstitutional ambitions, he attached great importance to his own public reputation and this sometimes made him tactless.

The Revolt of Spartacus

In the ancient world, the fate of war captives, if it was convenient to spare their lives, was normally to become slaves. Victorious Roman wars had consequently, before the beginning of the first century BC, filled Italy and Sicily with a slave population whose size had become an obvious danger. There had been violent slave revolts in Sicily in 139 and 104 BC, both of which had dragged on for several years, but the most serious of all such insurrections was that to which we have referred above (73 BC). It was led by Spartacus, a Thracian gladiator, a man of noble character and no mean intelligence, who was endowed with some Greek culture. Together with a band of comrades, he broke out of a gladiatorial barracks managed by private enterprise at Capua. The runaways equipped themselves with knives and spits from a local cookshop, afterwards supplementing these with a store of gladiatorial weapons. A military force from Capua was sent against them, but they routed the soldiers and took possession of their arms – a valuable acquistion for the slaves.

Now 3,000 troops from Rome, under a praetor, were sent against the insurgents. Spartacus and his followers were temporarily besieged on a precipitate summit, but they twisted the branches of wild vines to make ladders and escaped down a sheer rock face. Spartacus’ army was joined by runaway slaves of all nationalities, from all parts of Italy, and seems to have reached a strength of 90,000 – a figure which would account for its continued success against the Roman armies that confronted it. The consuls in Italy still normally shared four legions between them, while much bigger armies were posted abroad under pro-magistrates. However, the very size of the slave force, with its lack of men able to take command and the multitude of nationalities that went to its making, did not contribute to good order and discipline within its ranks. Spartacus led his men northward in the hope that they might pass the Alps and disperse to their homes, but many of them preferred a life of brigandage in Italy, and he was persuaded to turn south again.

Crassus, when appointed to deal with the rebels, was by no means immediately successful. One of his officers, commanding two legions, engaged the enemy in contravention of orders and was defeated with heavy casualties, while many legionaries, fleeing from the battlefield, left their weapons to increase the enemy’s already growing store. Crassus issued new arms on payment of deposit and apparently punished the cohort chiefly responsible for the rout by decimation, a traditional Roman military punishment: selected by lot, one man out of every ten was beaten to death.

Spartacus’ purpose in returning southwards, apart from that of satisfying his followers, had been to cross into Sicily and fan the embers of slave revolt which had continued to smoulder in the island since the earlier insurrections. Many slaves in this area were of Greek language and origin, and perhaps he hoped for some sense of national coherence such as would give him more control over his forces. He negotiated with a band of pirates – many of whom now ranged freely in the western Mediterranean far from their Cilician strongholds – but they failed to provide him with the transport they had promised and kept the deposit which he had paid for it.

Crassus at last managed to blockade Spartacus in a small peninsula at Rhegium, by means of an elaborate four-mile earthwork and fosse across the Isthmus. But on a wild, wintry night, Spartacus contrived to fill in the ditch and sallied out with a large part of his forces. It looked as though the slaves might march on Rome, but in Lucania some of them mutinied and formed a separate camp. These were engaged by Crassus, after some preliminary manoeuvring, and slaughtered to the number of 12,000. Spartacus, however, with the main body of the army, still remained at large. Crassus’ quaestor, who had pursued him into mountain country, was heavily defeated and was himself lucky to be carried away wounded. But discipline in the slave army remained poor, and Spartacus could not resist the demands of his followers for further confrontation with the Romans. This was precisely what Crassus wanted, being already afraid that Pompey and Lucullus, by their arrival from the West and East respectively, would steal credit for the victory which he had promised himself. In a decisive battle, Spartacus died fighting. Those of the slaves who survived the slaughter were captured by Crassus or Pompey and crucified.

Crassus’ trenching operations near Rhegium are worth noticing. The recourse to trench warfare, not necessarily associated with the blockade of a city or the fortification of a camp, was a Roman as distinct from Greek development. It was perhaps what one would expect from a nation of engineers who excelled in building roads, aqueducts and drainage systems. Perhaps it was a natural extension of camp construction, or perhaps we may see it as a logical step from Scipio Aemilianus’ fortifications at Numantia, where, as Appian observes, he was the first general to enclose within a wall an enemy who would have been willing to fight in the open field. If Scipio was the first, subsequent Roman commanders certainly showed themselves willing to learn from example, and it will be remembered how trenching operations had played an important part in Sulla’s eastern campaigns.