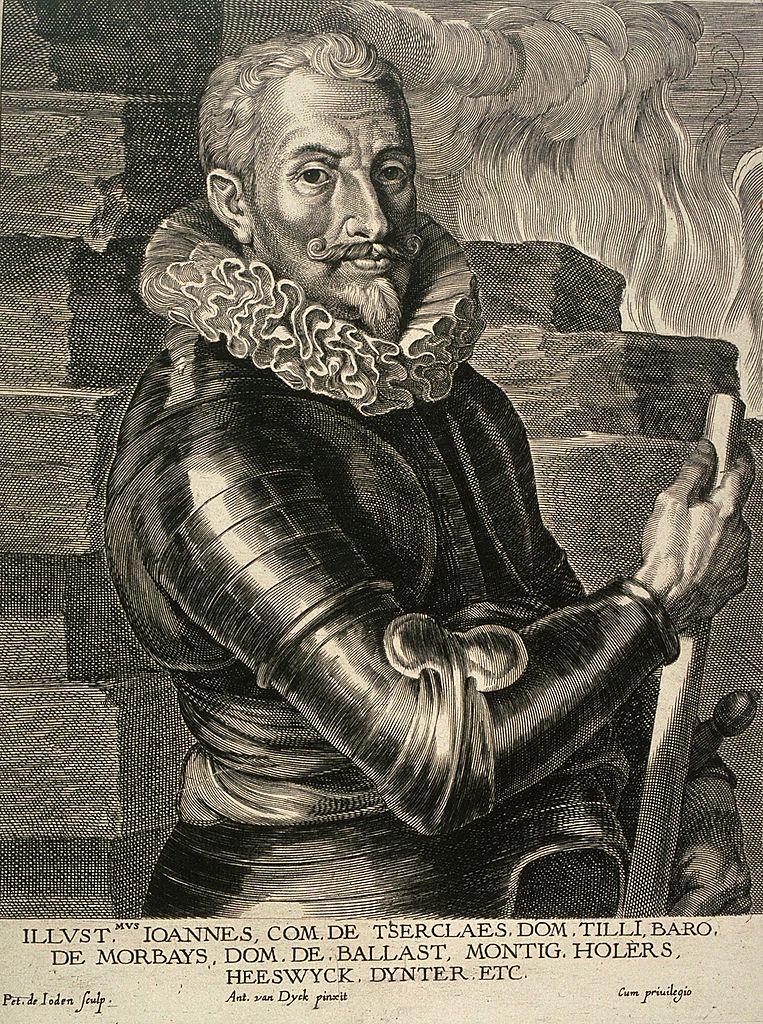

Count Tilly on a portrait by Anthony van Dyck.

Contemporary painting showing the Battle of White Mountain (1620), where Imperial-Spanish forces under Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly won a decisive victory.

Count Jean Tserclaes Tilly (1559–1632) was another outstanding product of Jesuit training. First seeing service in Spain, the Walloon learnt the art of war from the age of 15, serving under the Duke of Parma in his war against the Dutch. In 1610, he was appointed commander of the forces of the Catholic League, established in 1609 as a loose alliance of Catholic principalities and minor states. Like Wallenstein, Tilly brought in important reforms, especially from his experience of the formidable Spanish infantry. Nicknamed the ‘monk of war’, he soon proved to be a highly capable organiser of infantry tactics, which were quickly adopted by Ferdinand’s troops.

The infantry at this stage still consisted of pikemen and musketeers. The pikemen wore armour and carried a pike, which at that time was between 15 and 18 feet long, made of ash with a sharp metal point. Their officers carried shorter pikes with coloured ribbons. The musketeers were a kind of light infantry with a light metal helmet, later replaced by a felt hat. The heavy musket they carried needed to be rested on a wooden pole with an iron fork to be fired. The ‘ammunition’ was contained variously in a bandolier, a flask of gunpowder and a brass bottle of combustible material, the so-called Zundkraut as well as a leather bag containing small metal balls. A small bottle of oil was also carried to ensure that the ‘alchemy’ required to fire the weapon functioned smoothly. This was far from straightforward. A hint of the complexity of firing this primitive musket is given by the fact that ninety-nine separate commands were needed to fire and reload the weapon.

A further forty-one commands existed for dealing with the musket at other times. As this suggests, the need to increase the rate of fire and simplify the munitions were priorities for all commanders throughout the Thirty Years War. These problems would only be solved with the advent of the Swedes, who entered the fray against the Habsburg in 1630. They had a modern solution to many of these problems: the introduction of small cartridges wrapped in paper.

The only tactical unit at this time was the company, which was deployed in a large square made up usually of between 15 and 20 companies. This formation was 50 men deep with its flanks protected by 10 rows of musketeers. Despite much practice at marching to form such elaborate formations as the so-called ‘Cross of Burgundy’ or ‘Eight-pointed Star’, it takes little imagination to realise that manoeuvring in such formations was virtually impossible. The idea of marching to a single beat of the drum had still to be widely introduced and cohesive movement was only possible by extended rank.

Where Tilly proved so successful in organising infantry tactics, Wallenstein proved no less formidable in handling cavalry. Cavalry like infantry were divided into heavy and light. The heavy cavalry were cuirassiers and lancers, both armoured down to their boots. In addition to their main weapon, lancers were also armed with a sword and two pistols, symbols of their privileged status as bodyguards to the commanders in the field. The cuirassiers carried the heavy straight sabre or ‘pallasch’, which was designed to cut as well as thrust.

The horsed ‘carabiniers’ were organised as light cavalry as their only armour was a metal helmet and a light breastplate. Equipped with a shorter musket and 18 cartridges, these horsemen also carried pistols and a short sword. The dragoons were also equipped with a short musket and were indeed originally horsed musketeers. As the barrels of their muskets were often decorated with a dragon, they became known as dragoons. Deployed as advance guard cavalry they carried an axe with which, in theory, they could batter down doors and gates.

To these conventional groupings Wallenstein added new elements. An important part of the horsed advance guard was the ‘ungrischen Hussaren’, or Hungarian hussars. Together with the Croats they formed the irregular elements of the army who could be deployed to plunder and terrorise their opponents as well as perform scouting and reconnaissance.

The origin of the term ‘hussar’ to this day is a source of debate. The word most likely stems from the Slavic Gursar or Gusar. Other theories link the word to the German Herumstreifender or Corsaren; this last with its imagery of piracy perhaps being nearer to the truth than many a Hungarian would care to admit. Famous for giving their enemies no quarter, they became the nucleus of what would become the finest light cavalry in the world.

As with the infantry, the cavalry were grouped into companies. Often these were called Cornetten and hence the title of the junior officer of each such company was ‘Cornet’. As these were formed into a square, the custom arose to call four of these companies a ‘squadron’ from the Italian quadra, meaning square. In theory every cavalry regiment consisted of ten companies each of a hundred riders but in reality no cavalry regiment had more than 500 men.

Drill of these formations was aimed at disordering infantry by charging the last 60 paces at the enemy’s pikemen or cavalry. There was to be no firing from the saddle until the cavalry could ‘see the white in the eye of the foe’ (‘Weiss im Aug des Feindt sehen thut’). Led by such Imperial officers as Gottfried Pappenheim, famous for his many wounds and refusal to be impressed by titles, or the redoubtable Johann Sporck, a giant of a man with hair like bronze, perhaps the most feared cavalry general of his time, the Imperial cavalry was trained in shock tactics relying on aggression and surprise to demoralise their opponents.

The artillery remained a strict caste apart. Each unit of artillery was in theory organised to have 24 guns of different calibre. Mortars and other guns were added to each unit. Every gun had as its team a lieutenant and eleven gunners. These were supported by the so-called Schanzbauern or Pioneers, who were organised into units as large as 300 under an officer of the rank of Captain. The unit had its own flag made of silk which displayed as its badge a shovel and its men were also skilled carpenters able to strengthen bridges, not just demolish them.

Battle of Breitenfeld 1631

Leading his army to attack the Imperialists occupying Leipzig, Gustavus Adolphus was met en route by an Imperial army under Count Tilly. The Imperialist forces were deployed along a ridgeline with large cavalry forces on both wings. Gustavus arrayed his Swedish forces in two lines, each of which maintained a small reserve. The left of the Swedish line was held by their Saxon allies. The battle began with an artillery duel in which the quick-firing and more numerous Swedish guns held the advantage. The battle began as the Imperial cavalry, first on the left and then the right, surged forwards. On the left, they were held by the Swedish horse supported by musketeers, but on the right they routed the Saxons. Fortunately, the discipline and manoeuvrability of the smaller Swedish units allowed them to fill the gap on the left and to attack the Imperialist centre on the right, ultimately defeating the Imperial army.

The Battle of Breitenfeld showed the superiority of the ‘Swedish synthesis’ of the combination of firepower and shock coupled with superior discipline and organizational flexibility, especially when led by commanders with experience and initiative. As the Thirty Years’ War progressed, many armies, including the Imperialists, would begin to copy the smaller and more flexible units like the Dutch battalion or Swedish squadron.