In the meantime, James had asked for assistance. His Cornishmen, had suffered a steady toll of casualties from constant artillery and mortar fire, and from about 03:00 they were harassed by some of Hohenstaufen’s machine gun teams which had established themselves in the dry stone wall at the forward edge of the wood, approximately 100 yards from the British trenches.

The response to James’s request came in the form of a squadron of Royal Scots Greys, whose counter-attack bore a tragic similarity to their charge at Waterloo. At first, as then, all had gone well. Their Shermans had crossed the shallow summit and roared past both flanks of the little wood to silence or drive out the troublesome machine gunners. Unfortunately, this brought them within view of the enemy armour in the valley below and within minutes four had been set ablaze and a fifth exploded, its turret spiralling skywards before landing on its roof beside the burning hull. Wisely, the squadron commander decided to retire beyond the crest and give such support as he could from hull-down positions.

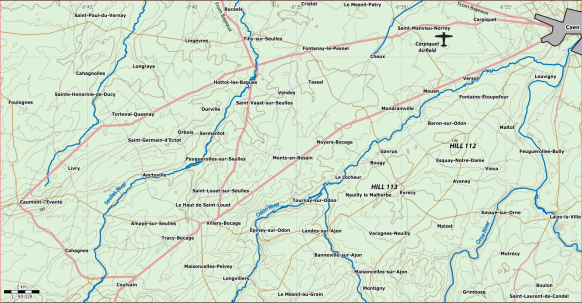

The German attacks began again at 06:15, converging from the directions of St Martin to the east and Esquay to the south. Initially they were made by the Panzergrenadiers of both divisions, strongly supported by artillery, mortars and machine guns, but they were decimated by the British defensive barrages and then cut to pieces by the Cornishmen’s rifle and light machine gun fire. There were times when the summit and slopes of the hill were invisible to German observers because of bursting shells. There were times, too, when the British FOOs called in their barrages to within 150 yards of their own position; one such was Lieutenant King, who, with complete disregard for his own safety, stood on an exposed bank the better to control his guns and is believed to have been killed by a splinter from a British shell.

As the morning wore on, 102 Battalion’s Tigers returned to spearhead the attacks while other tanks engaged the wood with high explosive, their shells bursting among the trees and sending a shower of jagged splinters hissing downwards into the slit trenches, for which there had been no time to provide headcover. The southern thrust of the German attack ran into a particularly violent storm of artillery fire controlled by a Lysander air OP, pinning down the panzergrenadiers. The Tigers, though enjoying some protection in the sunken lane up which they were moving from Esquay, were hit repeatedly. The high explosive shells could not penetrate the thick armour, but they could cause damage to the exposed running gear and the transmitted shock of exploding medium calibre rounds could cause internal problems such as ruptured fuel, coolant and lubrication lines or unseat machinery that would ultimately render the vehicle inoperable. For the moment, however, the Tigers were still capable of fighting. They broke into the paddock, blowing apart the anti-tank guns that tried to oppose them, then, while some engaged the Greys’ Shermans in a one-sided duel, others systematically destroyed the DCLI’s Carrier Platoon, which had come forward to deliver supplies and evacuate as many of the wounded as possible. Yet, with their own infantry still pinned down and mindful of their experience during the night, they did not attempt to penetrate the wood. One Tiger did not return from the attack and it may well have been this which approached the Somersets and was immobilised by one of the Greys’ Shermans, almost certainly a Firefly.7 When the crew came forward to surrender a few men opened fire on them, killing three. It was the act of those who were in action for the first time and had not yet come to terms with the bestiality of war. Having, in earlier attacks, seen friends of years’ standing literally blown apart in their trenches by the main armament of the enemy’s tanks, they were at that moment possessed by a blinding hatred for their crews. What had occurred was uncharacteristic and it was subsequently regretted.

It was about this time that Colonel James, having again climbed a tree the better to spot for the gunners, was shot dead by a burst from a German machine gun. The news that their young and popular commanding officer had been killed deeply saddened the Cornishmen, but it remains unclear precisely what happened next. Certainly there were very few senior officers left in the battalion and, for the moment, central control seems to have lapsed. The men were terribly tired, having been three nights without sleep, and their dead lay throughout the wood. Somehow, the rumour spread that orders to withdraw had been received and the companies complied; the source of the rumour has never been identified but one theory suggests that it might have been German.

The 4th Somersets, dug in some way to the rear, had become accustomed to the trickle of Cornish walking wounded passing through their position, but at about 11:00 this suddenly expanded as groups of clearly unwounded men, some running, others supporting wounded comrades, began heading for the rear. The suggestion of panic was emphasised by a DCLI officer trying to halt them; no one could understand what he was shouting because part of his lower jaw had been shot away. One of the Somersets’ platoon sergeants, noting how unsettled his own men were by the sight, threatened to ‘shoot the first bastard who moved.’ None of the ‘bastards’ did. It was Lieutenant-Colonel C. G. Lipscomb, commanding the Somersets, who recognised that the Cornishmen were not out of hand but simply confused, exhausted and near the end of their physical and mental resources. He rallied them quietly and divided them into their company groups, none of which were more than a platoon strong. Major Roberts, Major Fry, Captain Gorman, the adjutant, and the few remaining senior NCOs then led them back to the wood, where they reoccupied their positions. Half a dozen or so panzergrenadiers had moved into the trees during their absence but they had had enough and quickly surrendered. Meanwhile, anxious to reassure the Somersets that the crisis had passed, Lipscomb and Brigadier Mole seated themselves on their walking sticks and chatted amiably for a while, apparently heedless of their own safety.

For a short period the DCLI were left in comparatively undisturbed possession of the wood. At about 14:00, however, the enemy fire intensified in obvious preparation for another attack. This time it came in from the direction of Maltot, spearheaded by Hohenstaufen’s assault gun battalion.8 Some anti-tank guns remained to the Cornishmen on this flank but because of the configuration of the slope they could not be depressed sufficiently to engage the low-slung vehicles. The artillery was requested to lay smoke and under cover of this Lieutenant Bellamy had one of the 17-pounders manhandled forward until it would bear. Despite the fact that he and his crew were only able to fire a few rounds before the gun was put out of action, they seem to have scored several kills, for in his report the German commander records that three of his assault guns were knocked out and three more received direct hits, the latter probably by artillery fire. That left four to complete the task, but in the event it was to prove sufficient.

By 15:00 Roberts had been wounded and the battalion’s strength had shrunk to about 100 men. Gorman had been despatched to inform the brigade commander personally that the position was becoming untenable. The assault guns were closing in, slamming high explosive shells into the wood and raking it with machine gun fire. With casualties mounting and close quarter anti-tank defence now limited to a handful of PIAT bombs, Fry, now the senior surviving officer, sent a runner to brigade with the recommendation that the remnant of the battalion should either be relieved or permitted to withdraw behind the crest. No answer was received.

He was now on the horns of a terrible dilemma. To abandon the position without orders could result in serious personal consequences; on the other hand, the Army’s code would support him if, as the man on the spot, he acted with considered judgement in the light of the prevailing circumstances. Only two alternatives existed. Either he could withdrew his men, who would then form a nucleus upon which the battalion could be reconstructed; or, he could fight on in the certain knowledge that the position would be overrun in a few minutes. Whatever he decided, the wood was about to fall into German hands, anyway. In the circumstances, he decided to withdraw and, under cover of a smoke screen, the Cornishmen pulled back, carrying their wounded with them, to take up a new position behind the 4th Somersets. For the rest of his life Fry was haunted by the thought that he should have hung on and fought to the bitter end, but that would only have resulted in annihilation to no purpose. As it was, 5 DCLI had incurred 320 casualties in fifteen more or less continuous hours of battle, and of these 93 lay dead in and around the little wood; with justifiable pride, the regimental history records that only one man was taken prisoner. Incredibly, the heroism and tenacity of so many of the battalion’s officers and men was not recognised by the award of a single decoration.

The withdrawal of 5 DCLI marked the virtual end of Operation Jupiter. True, the summit of Hill 112 remained a no-man’s-land, but the operation had achieved its strategic objective of tying down the German armour. Fighting erupted again during the night of 15 July and continued for the next fortnight. While the summit of the hill was masked by smoke and high explosive, the 43rd, 15th and 53rd (Welsh) Divisions in succession, supported by the Churchills of 31 and 34 Tank Brigades and Crocodiles, mounted a series of heavy raids on the nearby villages – Le Bon Repos, Esquay, Evrecy and Maltot. These, as intended, provoked fierce counterattacks which further wrote down the German armour. On 18 July Operation Goodwood, a drive by three British armoured divisions north of Caen, was halted by a strong anti-tank defence but convinced the German High Command that the Allies intended breaking out on the British sector. On 25 July the American breakout, codenamed Cobra, began and soon the US Third Army was sweeping round the German left flank. Simultaneously, the British and Canadians were driving in the enemy’s right. By the middle of August the German armies in Normandy, held fast within the jaws of a trap, had been systematically destroyed.

It would be difficult to overemphasise the part played by the sustained and costly pressure maintained on the Hill 112 sector in achieving this complete victory. Forced by events elsewhere to withdraw, II SS Panzer Corps left the area during the night of 3/4 August. A few days later some members of 5 DCLI’s Assault Pioneer Platoon erected a board on the summit showing the regimental badge and the words CORNWALL HILL JULY 10th-11th 1944. Other regiments, too, felt that they had some claim on the hill but they knew what the Cornishmen had been through and not only let the board stand but also referred to the little wood as Cornwall Wood in their own histories. Later, the 43rd Division, which was to fight many battles but none so bitter as that for Hill 112, erected its own granite memorial on the same site.

The story had a postscript. In 1945, following the German surrender, Major Roberts became commandant of a prisoner of war camp and had the opportunity of interrogating two SS men who had fought at Hill 112. One had served in 102 Heavy Tank Battalion and he recalled that of the nine or ten Tigers that had attacked the wood during the night only two returned undamaged. The other was one of Frundsberg’s panzergrenadiers, who stated that the regiment which had borne the brunt of the fighting had been reduced to five or six men a company. In fact, by the time of the final German collapse in Normandy Hohenstaufen and Frundsberg had each been reduced to the strength of a weak infantry battalion with only the former retaining a few of its tanks and guns. The once-mighty II SS Panzer Corps, now a skeleton of its former self, was sent to Holland to refit.

Notes

1. See Against All Odds! Chapter 2.

2. See Seize and Hold Chapter 5.

3. Ellis, Major L. R, et al, Victory in The West Volume 1, The Battle of Normandy, HMSO, London, 1962.

4. The tank destroyer was essentially an anti-tank gun housed in an open-topped turret mounted on a tank chassis. Those serving with the British and Canadian armies in Normandy were the MIO, known in British service as the Wolverine, armed with a 3-inch high velocity gun, and the Achilles, which was the MIO upgunned with a British 17-pounder anti-tank gun. The Royal Artillery, responsible for anti-tank defence at the higher levels, was lukewarm about the concept of tank destroyers but recognised that in the close bocage country they not only possessed the ability to engage over the hedge-topped earthen banks but could also be got forward to support the infantry in a newly-captured position much more quickly than towed guns; during set-piece infantry/tank attacks, too, their powerful armament went some way to redressing the balance between the undergunned Churchills and the enemy’s armour. For these reasons, therefore, the Royal Artillery’s anti-tank regiments were equipped with a proportion of tank destroyers.

5. The Army Group Royal Artillery (AGRA) generally contained one heavy and three medium regiments but was flexible and could also include one or more field or anti-aircraft regiments with the latter firing on ground targets. AGRAs were usually allocated on the scale of one per corps plus one in reserve.

6. The Crocodile’s flame fuel was housed in an armoured trailer. This apart, the vehicle was virtually indistinguishable from a Churchill gun tank save at very close quarters. The defenders of Eterville can hardly be blamed for failing to evaluate the purpose of the trailer.

7. A Sherman upgunned with a British 17-pounder, usually issued on the basis of one per tank troop.

8. Assault gun units were primarily intended for the close support of infantry operations and were composed of artillerymen. There were many types of assault guns, the most common being based on the PzKw III chassis, a 75mm gun with a limited-traverse mounting being housed in a low, enclosed superstructure at the front of the vehicle.

9. Both divisions were still refitting at Arnhem in September and were responsible for the isolation and defeat of the British 1st Airborne Division during Operation Market Garden. During these operations the 43rd (Wessex) Division again clashed with Frundsberg in the area between Nijmegen and Arnhem. Subsequently, although Hohenstaufen took part in the Battle of the Bulge, neither SS division achieved much and both ended their days on the Eastern Front.