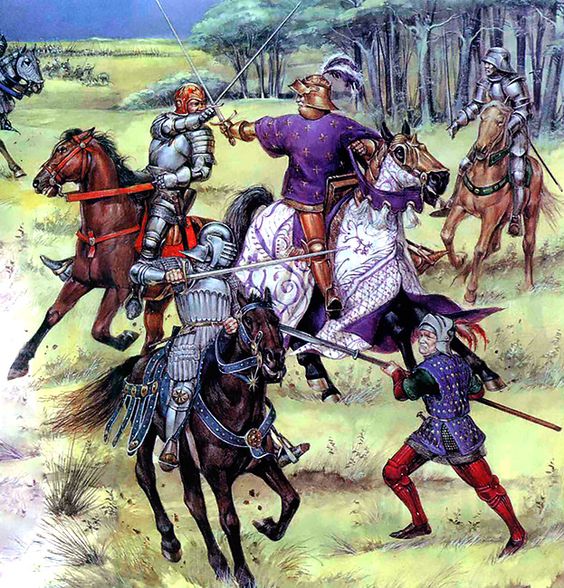

Charles VIII is attacked, Battle of Fornovo, 6 July 1495.

The first full scale battle of the wars was fought at Fornovo in July 1495. Charles’ triumph in conquering Naples was short-lived. Those internal elements which had contributed to the overthrow of the Aragonese dynasty soon realised that French rule was not a satisfactory alternative, and increasing unrest made the position of Charles’ army a difficult one. The Italian states, with the exception of Florence, which was now permanently committed to the French cause, came together in an alliance to evict the French, and began to receive increasing encouragement from Spain and the Empire. At the end of May, Charles decided to return to France with the core of his army, leaving a skeleton force under Montpensier to defend Naples. The armies of the Italian League began to gather to oppose this return march, but there was still little real political unity, as some thought it best to let the French pass on their way out of Italy rather than risk a confrontation with them. However, the opportunity, as Charles marched northwards with a relatively small army, was too good a one to be missed and Francesco Gonzaga, the Marquis of Mantua, Venetian captain general and commander of the combined army, elected to bring the French to open battle rather than simply hold the Apennine passes against them. The latter course would have involved little risk and could well have led either to the eventual surrender of the army as it was cut off from its base, or at least to a hazardous transhipment by sea. It would have been a strategy very much in the Italian tradition, but Gonzaga felt both sufficiently confident and sufficiently determined to achieve the personal glory of defeating the French, to go for a crushing victory.

The French retreated along the route they had come in the previous year. This meant crossing the Apennines between Sarzana and Parma by the Cisa Pass, and coming down into the valley of the Taro at Fornovo. Here, below the town where the valley widened out, the huge Italian army was waiting for them in a camp fortified with a ditch and a palisade. Gonzaga described his army as ‘the finest and most powerful that has been seen in Italy for many years’. It numbered about 25,000 men of whom about 5,000 were in Milanese service and the remainder in that of Venice. Two thousand two hundred heavy cavalry lances of five men each formed the core of the army, but there were also about 2,000 light cavalry, mostly stradiots, and 8,000 professional infantry. Four thousand Venetian militia had also arrived, although the bulk of the militia forces were still on the march, as was most of the Venetian heavy artillery. The French numbered about 900 lances of heavy cavalry, 3,000 Swiss infantry, 600 archers of the royal bodyguard and 1,000 artillerymen, a total of about 10,000 men.

When it reached Fornovo, the French army crossed the Taro and began to move down the left bank of the river in front of the Italian camp. Its left flank was thus protected by the hills and its right by the river. In the circumstances the French not surprisingly expected the main assault on them to come from straight up the valley, and to counter this the Swiss marched in a tight square close behind the cavalry advance guard. Two further large columns of cavalry completed the order of the march with the King commanding the centre himself and the rear led by Gaston de Foix. The baggage train laden down with loot from the campaign was placed towards the rear and close to the line of the hills; the artillery moved on the right flank along the river bank.

The Italian battle plan was drawn up by Ridolfo Gonzaga, uncle of the Marquis and himself a veteran of the Burgundian wars, with just these dispositions of the enemy in mind. The tactical conception was masterly, although the details for its execution were over-elaborate. Basically the plan was to block the French advance with a holding force and launch the main attack across the Taro on the flanks of the centre and rear columns. This would have the effect of pinning the enemy against the hills, splitting his extended line of march, and destroying the columns in detail. To carry out this operation the Italian army was divided into nine divisions. The Count of Caiazzo, with the main body of the Milanese cavalry and supported by a mixed infantry force and a large cavalry reserve, was to cross the Taro in front of the French and engage the vanguard. Gonzaga himself with his personal troops was to cross in the centre, engage the French centre, and split it off from the vanguard. Bernardino Fortebraccio had command of the third prong of the attack, made up of the leading Venetian cavalry squadrons, and was to attack the rearguard. In close support to Gonzaga and Fortebraccio came the cream of the Venetian infantry, and then in reserve two further columns of cavalry. The first of these comprised the lanze spezzate known as the Colleoneschi and commanded by the son-in-law of the legendary Colleoni, who had died nearly twenty years earlier. The second reserve column was led by Antonio da Montefeltro, the illegitimate son of that other leading figure of the preceding generation, Federigo. While all these divisions were attacking directly from across the Taro, the stradiots were to pass right around the rear of the enemy and attack the vanguard downhill, thus causing further confusion and preventing stragglers from escaping into the hills. Finally a strong guard of cavalry and militia was left in the camp.

The intelligent use of reserves has sometimes been described as one of the distinguishing features of modern military tactics, and the concept was certainly one that had been widely explored by the condottieri. But in this case there was too much emphasis on reserves. Whether this was because Gonzaga had more men than he knew what to do with or whether it was a sort of natural caution is hard to say. However, part of the intention was clearly to prevent the reserves being committed too early or all at once, and the leaders of the various reserve divisions had strict orders not to enter the fray until called forward by Ridolfo Gonzaga and no one else.

The battle opened in mid-afternoon with a brief artillery duel across the Taro. But heavy rain had dampened the powder and the guns on both sides were more than usually ineffective. The rain had also swollen the river suddenly, and this was seriously to affect the Italian plan. When the signal to advance was given the three spearhead columns began to cross the river. The Count of Caiazzo attacked the van with indifferent success; his infantry were badly cut up by the Swiss who outnumbered them, and elements of his troops were soon fleeing towards Parma. However, he achieved his task of keeping the French vanguard occupied. The stradiots also reached their first objective and harried the French left flank. But when two of their leaders were killed, they drew off and began to plunder the baggage train, which their encircling movement had placed at their mercy. In the centre Gonzaga found it impossible to cross the river where he had intended and moved further upstream to cross close to Fortebraccio’s troops. This led to delay and some confusion; but above all it meant that instead of striking the gap between the French centre and the already committed vanguard, he crossed between the centre and the rearguard, thus exposing his flank to the full weight of the French centre. Here in the space of less than an hour the battle was decided. The element of surprise was lost by the delays, and Gonzaga and Fortebraccio found their squadrons depleted by the difficulties of crossing the river. They bore the full brunt of the counter-attacks of the French and no reserves came forward, as Ridolfo Gonzaga was mortally wounded at the height of the battle. Thus more than half the Italian army never got into action at all. The heavily mauled divisions of Gonzaga and Fortebraccio gave almost as good as they got; the two leaders particularly fighting with exceptional gallantry. At one point they came close to capturing Charles, but so furious a battle could not last for long. Both armies drew back to regroup, and then approaching darkness prevented a resumption of fighting.

The outcome of the battle appeared uncertain, and both sides claimed a victory. The French had achieved their aim of opening a road northwards, as they were able to resume their march stealthily the next night. They had inflicted the heavier casualties on Gonzaga’s army which lost over 2,000 men, including a number of captains. The Italians could claim to be the masters of the field as the French drew off, and they captured the French baggage, including Charles’ personal illustrated record of his many amorous conquests. They also took more prisoners. These perhaps, in terms of Italian warfare, were indications of victory; but Fornovo was fought for specific objectives, and Gonzaga failed to achieve his objective; so he can be said in real terms to have lost the battle. But he lost it not because the Swiss infantry and French artillery were invincible; neither of these elements played much part. Nor did he lose it because the French fought better or with more determination. He did not even lose it because a part of his army got out of hand, notably the stradiots, and another part, the Milanese, did not press their attack (perhaps on instructions from Milan), although these were the excuses given for the lack of success. Three factors really contributed to the Italian failure. First there was the sudden rising of the Taro which badly disrupted the Italian plan and caused last minute confusion. Secondly both Francesco Gonzaga and his uncle elected to lead the army, and thus no one was really in a position to direct the whole battle. Gonzaga, although he showed great personal bravery and many of the ideal qualities of a subordinate commander, had not appreciated that so large and complex an army needed to be directed from behind.

This was by no means a typical Italian mistake; neither Braccio nor Sforza would ever have allowed themselves to make it. Finally the sheer size of the army and complexity of the battle plan frustrated success. This sudden attempt to translate tactics which could work well with a small army used to cooperation to a large composite army which had come together for the first time, was bound to run into difficulties. More traditional tactics would probably have won the day by sheer weight of numbers, which is a curious reflection on the theory that Italian methods were outdated and superseded.

Fornovo was one of the two major battles in the whole period between 1494 and 1530 when a largely Italian army met the invaders in the open field. It is therefore one of the few occasions when one can seek to assess the relative merits of Italian and ultramontane military methods. For the rest of the time the political disunity of Italy and political weakness of most of the states made combination against the invaders and a real trial of strength impossible. Italians fought, sometimes distinguished themselves, and occasionally disgraced themselves, on both sides in the wars, but the warfare was increasingly becoming international rather than Italian. It only remains therefore to analyse briefly the Italian contributions to the changes which were taking place during these protracted wars.