Armored trains were first used in battle during the American Civil War (1861–1865) and were subsequently deployed in the Boer War and in the Russo–Japanese War, among other conflicts, but are more associated with the “Russian” Civil Wars than any other. The fact that, together with the tachanka, armored trains played such a significant part in the “Russian” Civil Wars (and indeed became emblematic of it) indicates the extent to which, in contrast with recent wars, such as the First World War on the Western Front, it was a war of movement.

Although it was more static than the civil-war fronts, the Eastern Front of 1914–1918 had also been mobile to a greater extent than the Western Front, and it was there that from 1915 armored trains first began to be used by the Imperial Russian Army as mobile artillery platforms. There were seven of them in use by mid-1917. In the civil wars, however, the armored train became hugely important for all sides, as the spearhead and focus of advances and retreats that were usually made along (or close to) railway lines (and not only in the railway war). It is surprising that the side with the most armored trains (and the greater ability to repair and replace them) won most of the “Russian” Civil Wars.

Red Armored Trains:

On 21 January 1918, the Central Council for Control of the Auto-Armored Units of the Republic (Tsentrobron) was established to oversee the construction and administration of all Red armored units, including (from April 1918) armored trains. On 3 January 1919, it merged with other bodies to become the Chief Directorate of Armor and this, in turn, was reformed into a new, larger institution on 1 October 1919: the Armor Department of the Chief Military Engineering Directorate.

The Reds had the advantage of inheriting almost all tsarist railway stocks, supplies, and personnel for the production of armored trains (although some experts joined the Whites) and were able to produce them in relatively large numbers and relatively standard forms (thereby facilitating repair). On 1 October 1918, there were 43 trains at the Red fronts. By 1 October 1919, there were at least 73. On 1 July 1920, 110 trains were registered, although only about 90 were in service. On 1 October 1920, following the damaging battles of the Soviet–Polish War, the corresponding figures were 103 and 74. Some two-thirds of the trains were constructed at factories at Petrograd, Moscow, Nizhnii Novgorod, Kolumna, and Briansk. Most of these units were configured of an armored engine, two armored wagons (each containing two, rotating, usually cylindrical gun turrets), and an armored tender, with two control wagons positioned at the front and rear and, occasionally, further wagons to the front and rear that were either empty or contained nonvital supplies. (The purpose of the latter was to take the shock of a first artillery strike from an enemy train further down the line, to act as a buffer against unmanned locomotives and cars packed with explosive that might be sent down the line, or to detonate mines before they could damage the essential parts of the echelon.) Weaponry could be in the range of from two to four three- to six-inch artillery pieces and four to sixteen machine guns. The armor plate was in the range of one-half to one inch in thickness, and most trains were double armored for further protection (sometimes with springs or even concrete separating the two plates). As such, these behemoths had a top speed of only 30 mph and a range of only 15 miles without taking on new stocks of water and were further hampered by the fact that many of the country’s wooden bridges would not bear their weight. Coal supplies were extremely limited, and most trains were fueled by wood, again limiting their efficiency.

Because the trains were complicated to use and expensive to build and run, their crews were highly trained by Red Army standards and would generally include a high proportion of party members (sometimes, as on Trotsky’s Train, almost 100 percent). Training courses began in Moscow, in April 1918, at the Armored Car Garage, which by early 1919 had become a formal Academy of Armor. Similar institutions were developed at Nizhnii Novgorod and Briansk.

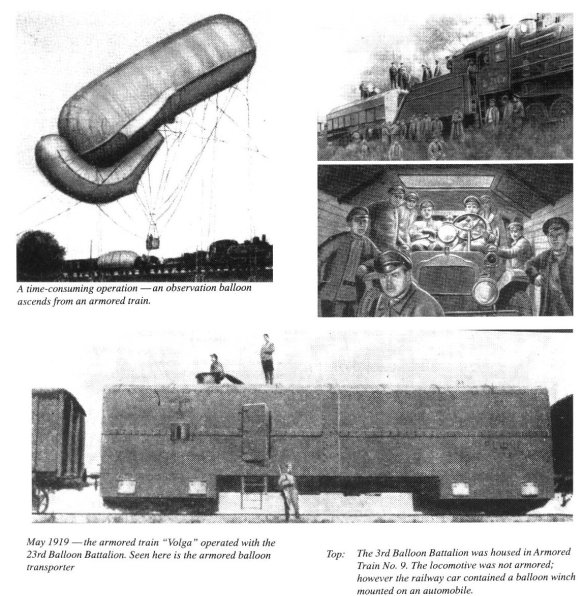

In the course of 1918, Red armored trains came to be designated as either “heavy” or “light,” depending on the scale of their armor and weaponry. Generally, in battle one of each class was expected to work in tandem, with the heavy train stationed in the rear and providing an artillery barrage, while the more mobile, light train made forays against the enemy (although this did not always happen). An attached supply train would also be stationed in the rear and could act as a base. Other combat configurations involved attaching cavalry or machine-gun detachments to the trains, or even aircraft and balloon units (as in the case of Armored Train No. 85, which patrolled the southern coastline in the spring of 1920). Such configurations, however, were generally found to be too unwieldy, necessitating lengthy echelons of supply and accommodation trains to accompany the armored echelons. In August 1920, new designations were given (in ascending order of caliber of weapons and weight of armor): Type A1–A2 (three-inch guns); Type B1–B6 (four-and-one-half- to five-inch guns), and Type V1–V5 (six- to eight-inch guns). A separate Type M (Morskoi, i.e., naval) train was also developed to guard ports and coastlines.

Armored trains were used by the Red Army in the earliest clashes of the civil wars in early 1918, against the forces of the Ukrainian Central Rada before Kiev and against the Don Cossack Host in the southeast. However, perhaps the most dramatic early use of an armored train by the Reds was on 12 September 1918, at Simbirsk, when Armored Train No. 1 (The Minsk Communist, in Honor of Comrade Lenin) was sent across the mile-long bridge across the Volga (behind a driverless locomotive to clear the tracks and followed by a brigade of infantry), forcing units of the Komuch’s People’s Army to abandon the city to the 1st Red Army. Thereafter, they were utilized on every front, but were especially prominent in actions in the south, west, and northwest, where the railway network was denser. In contrast, there were few lines in North Russia, while practical problems arose during the invasion of Poland in August 1920 because of the break-of-gauge between the five-foot Russian system and the narrower Polish network.

A problem encountered on all fronts was that enemy troops could sever the tracks in the rear of a train, thereby leaving it stranded. Sudden shortages of fuel, or natural disasters, such as floods and rock falls, or a fire on a wooden bridge (often caused by a spark from a passing engine) also made the echelons vulnerable to capture. The consequence was that a train might change sides on several occasions during the course of the war. For example, the Red Armored Train Comrade Voroshilov was captured by Ukrainian forces in early 1919, repainted, and renamed the Sichovyi, just in time for it to be captured by the invading Polish forces on 24 May 1919. They renamed it the General Dowbór. On 23 June 1920, it was captured again by forces of the 1st Cavalry Army and reclaimed for the Red Army.

White Armored Trains:

As all the armored trains of the Imperial Russian Army of the First World War fell into the hands of the Reds, the Central Powers, or the Ukrainian authorities in 1917–1918, the incipient White forces were left with nothing. Moreover, as railway stocks and factories and alternative construction opportunities were sparse in the peripheral regions they initially controlled, the Whites had to rely at first on trains captured from the Reds or on hastily improvised armored units. (The “armor” of one such train operating on the Kem–Kandalaksha line in Karelia in 1918, for example, is reported to have consisted predominantly of corrugated iron.)

Still, by the middle of 1919, the White forces across Russia had at least 79 armored trains in the field. These usually consisted of armored locomotives and flat wagons with armored walls and embrasures and turrets for cannons or machine guns—like those of the Reds, the White trains were usually protected at the front and rear by expendable wagons that would act as buffers against attacks by driverless trains, mines, or artillery firing down the line—but might also consist of heavy naval guns mounted onto wagons or even of armored cars and tanks that had been fixed to a train. Either Russian- or Allied-produced units might be utilized in the latter configurations. For example, in August 1918, two 12-pounders and one six-inch naval gun were taken from the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Suffolk at Vladivostok, mounted on flat wagons, and sent into action against Red partisans along the Ussurii line in the Maritime Province. The train was then sent to the Urals front and was deployed from November 1918 near Ufa, where the three guns were distributed among three separate echelons with considerable effect. In May 1919, gunners from the cruiser HMS Suffolk arrived with a replacement six-incher, and all the weapons were transferred onto vessels of the White’s Kama Flotilla before seeing action in the spring offensive of the Russian Army. In June 1919, they were transferred back to a single armored train echelon and joined the White retreat to Vladivostok.

In fact, however, there was a notable shortage of armored trains attached to the forces of Admiral A. V. Kolchak. According to some sources, only four quite primitive White armored trains were in operation west of the Urals during his Russian Army’s spring offensive of 1919. Meanwhile, in east the men of the Czechoslovak Legion jealously guarded their own powerful echelons, such the Orlik (not least because they served as the only available accommodation for the legionnaires), while Ataman G. M. Semenov was said to command at least 14 trains in his Transbaikal fiefdom, where they were used only to terrify the population and to hold up supply trains destined for the front. (The armor for some of Semenov’s trains—including his own personal mobile fortress, the Terrible—was apparently derived from breaking up and melting down the boilers of dozens of sorely needed locomotives, but this was a war in which no ataman worth the name could be without his own squad of armored trains.)

In North Russia, conditions did not suit the deployment of many trains (of the two major railways, the Murmansk–Petrograd line was narrow gauge, while the 425-mile line from Arkhangel′sk to Vologda traversed no fewer than 262 wooden bridges, rendering trains liable to sabotage or capture). Still, the considerable British naval presence in the region meant that some trains near Arkhangel′sk were equipped with naval guns, the Admiral Kolchak and General Denikin among them. Another Admiral Kolchak operated in northwest Russia, supporting the North-West Army, but it was in South Russia that White armored trains were most numerous. The Volunteer Army captured six trains during and immediately after the Second Kuban March of the summer of 1918, renaming them the General Alekseev, the General Kornilov, the Officer, the Forward for the Fatherland, the Battery of Distant Battle (later the United Russia), and the Naval Battery of Distant Battle, No. 2 (later Dmitrii Donskoi). During the spring of 1919, these and other echelons were used with tremendous skill by General V. Z. Mai-Maevskii to shuttle troops around the Don region and to launch numerous surprise attacks against the 8th Red Army and the 13th Red Army, before the Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR) set out on its Moscow offensive that summer. By October 1919, capturing and renaming Red trains as it moved north, the AFSR had increased its inventory to some 65 echelons of various sizes and capacities. By April 1920, however, as General P. N. Wrangel’s Russian Army was organized in Crimea, that number had shrunk to about 15, grouped into a railway battalion of five detachments commanded by Major General I. I. Kaliks. Most of those were captured by the Red Army as it advanced into Crimea in November, but the Reds were denied the echelons United Russia and St. George, Bringer of Victory, which were destroyed by means of a deliberate collision near Sevastopol′ on 14 November 1920, as the last White forces evacuated the city by ship.