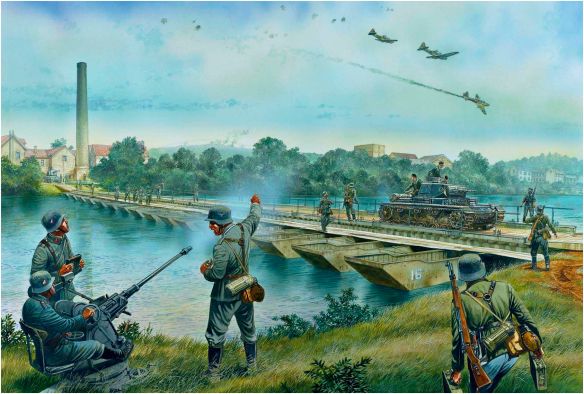

The German lightning strike was producing better results than even Hitler had expected. Guderian’s panzers had reached Abbeville and Amiens by 20 May and nearly one million Allied troops were isolated in the north by the Panzer units racing to the Channel coast. The best elements of the British and French armies, and all of the Belgian army, were cut off and could not be resupplied except through a few of the Channel ports.

In the last days of the blitzkrieg on France, she was also subjected to a short but noteworthy procession of staggeringly inept generals in top command roles. Elderly, exhausted, and essentially devoid of any practical ideas for turning back the evaders, this little parade contributed nothing but more confusion to the sad situation; all soon lost their will, the plot, and finally the fight.

The advance of the panzers continued unabated to the French coast. With the end of May came the end of the Battle of France and the most powerful and impressive armoured sweep the world had ever seen.

Trapped at the French seaside town of Dunkirk, 338,000 troops, mostly from the British Expeditionary Force, along with some French and Belgian units, now faced likely annihilation at the hands of the German invaders. Field Marshal Rundstedt sat behind the town with his five Army Group A armoured divisions, poised to destroy the massive Allied congregation which was gathered mainly on or near the beaches. He certainly had the firepower and the will to complete the task, but it was not to be. Rundstedt: “If I had had my way the English would not have got off so lightly at Dunkirk. But my hands were tied by direct orders from Hitler himself. While the English were clambering onto the ships off the beaches, I was kept uselessly outside the port unable to move. I recommended to the Supreme Command that my five Panzer divisions be immediately sent into the town and thereby completely destroy the retreating English. But I received definite orders from the Führer that under no circumstances was I to attack …”

It seemed that Hitler believed that his panzers had been severely strained in their race across France. He dared not risk them in a direct assault over the difficult terrain around Dunkirk when he needed to deploy them against the remaining French armies to the south. So he gave the job of wiping out the beach-bound BEF to Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe which he felt could easily destroy the enemy forces by bombing them. His misjudgement allowed most of the British troops to be evacuated from the beaches when the Royal Navy, together with an improvised fleet of vessels including coasters, paddle steamers, fishing boats, colliers, yachts and other craft, managed to rescue them. British losses during the evacuation amounted to 68,111 killled, wounded or taken prisoner.

In the wake of the offensive and the Dunkirk evacuation, lies the assumption which has persisted for many years since the war, that it was Hitler who ordered the German Army to stop its assault on the Allies there, as he preferred to allow Goering’s Luftwaffe to complete the operation with bombing.

However, according to the official War Diary of German Army Group A, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, Chief of the General Staff, had been concerned about the vulnerability of his flanks and the supply capability to his forward troops, and he ordered the halt. Hitler had simply rubberstamped the order. At the same time, Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering talked Hitler into letting the Luftwaffe destroy the trapped British and French forces, to the great displeasure of the High Command Chief of Staff, Franz Halder, who questioned the decision and was concerned about the Luftwaffe’s dependency on the weather conditions at Dunkirk. The German dithering and delay gave the British the time they needed to set up and carry out the bulk of the evacuation. Supposedly, Rundstedt’s order to halt of 23 May was confirmed by Hitler on the 24th, but on the afternoon of the 26th Hitler ordered the armoured forces to resume their advance, the delay having enabled the Allies sufficient time to establish the defences needed to support the evacuation.

In the opinions of various high-ranking German commanders, including Admiral Karl Dönitz, and Generals Erich von Manstein and Heinz Guderian, the failure of the German High Command to eliminate the BEF and French forces at Dunkirk was one of the greatest errors the Germans made on the Western Front.

The period of the Fall Gelb (Case Yellow) offensive and the Battle of France was a bitter, humiliating one for the French and British. When the cream of the French armies had been sent north, they, along with their best armoured formations and heavy weaponry, had been lost in the enemy encirclement. With a depleted army, Général d’armée Maxime Weygand had to defend a front line that ran from Sedan to the Channel, without much Allied support. The Allies had lost sixty-one divisions in Fall Gelb and Weygand had only sixty-five remaining, while the Germans still retained 142 divisions.

Almost incredibly, the French somehow managed to regroup and rejuvenate through the last three weeks of June, putting up strong resistance when the Germans restarted their offensive after 5 June. In the period, the French were able to replace much of the equipment lost earlier in the offensive, all of which contributed to a heightened overall morale among the French Army. It seemed to stem from the recent tactical experience gained by the French officers against the German armoured forces, and greatly increased confidence in the French weaponry and tanks after comparing them to the those of the enemy. They now knew that the French tanks of the day were better armed and armoured than their German counterparts.

Tactically, Weygand seemed to have taken hold of his forces and was now getting much more from them. The forty-seven divisions of German Army Group B, meanwhile, were making little progress in their attacks around Paris. The XVI Panzerkorps of Erich Heopner, now with more than 1,000 armoured fighting vehicles, was achieving even less at Aisne where, in its initial attack it lost eighty of the AFVs and the Germans struggled to cross the river there, frustrated by the deep defence that Weygand had established in the area. And the stiff artillery defences he had set up at Amiens were consistently driving the Germans back. It took fully three days of the renewed offensive before the German land forces, with considerable help from the Luftwaffe, were finally able to force some river crossings. A German comment on the action: “[it was] … hard and costly in lives, the enemy putting up severe resistance, particularly in the woods and tree lines, continuing the fight when our troops had pushed past the point of resistance.” Then the French forces began to weaken. To the south of Abbeville, the 10th French Army was forced to retreat to Rouen. It provided the opportunity for Erwin Rommel and his 7th Panzer Division to roll west across the River Seine through Normandy where they captured the port of Cherbourg on 18 June, accepting the surrender of the 51st British Highland Division on 12 June along the way to Cherbourg. The continuing attentions of the Luftwaffe were adding greatly to the problems of the French, dispersing their armoured forces and undermining their ability to function under the frequent air attacks.

By 10 June Paris was being seriously threatened by the 18th German Army and, finally, on the 14th, the French resistance gave way and the city fell to the German invaders. Throughout June the German armies were launching new offensives in the west. German Army Groups A and C were involved in a combined effort to encircle and capture the French forces on the Maginot Line and take the fortifications of the Metz region in order to stave off a possible French counter-offensive from the Alsace against the German front line on the Somme. The assignments had Guderian’s XIX Corps rolling to the French border with Switzerland to encircle the French forces in the Vosges Mountains. The XVI Corps was to attack the Maginot Line, approaching it from the west and its more vulnerable rear. They were to take the cities of Verdun, Metz and Toul. The French had recently repositioned their 2nd Army from Alsace to the Weygand Line along the Somme. They had left only a small force to guard the Maginot Line. Army Group B, meanwhile, was undertaking its offensive against Paris and from there on to Normandy. Army Group A began its advance on the rear of the Maginot Line, and Army Group C then began a frontal assault across the River Rhine into France.

Prior to these efforts, the Germans had had no success in trying to break into the Maginot fortifications, but now on 15 June, they greatly outnumbered the French. This time the determined Germans literally brought up their big guns, 88mm, 105mm and several railway batteries. Added to this was the air force’s V Fliegerkorps for air support.

Gradually, the Germans attacked and overcame the resistance offered by the French as each of the major Maginot fortresses was targetted. Progress was made on 17 June when the French 104th and 105th Divisions were pushed back into the Vosges Mountains elements of the VII Army Corps, and that same day Guderians XIX Corps arrived at the Swiss border. By then much of the Maginot defences had been cut off from the rest of France, most of the fortress units surrendering by 25 June. The Germans claimed to have taken some 500,000 prisoners of war in the actions.

By mid-June the Luftwaffe had achieved complete supremacy of French airspace. Goering’s Luftwaffe, still smarting after the failure to destroy the BEF and French forces in the Dunkirk rescue, was determined to prevent any further evacuation attempts by the Allies. In a mini-campaign to that end beginning 9 June, the Germans bombed Cherbourg, Le Havre and various Allied shipping including the liner RMS Lancastria out of Saint Nazaire, resulting in the loss of 4,000 Allied personnel. Still, despite the efforts of the Luftwaffe, nearly 200,000 additional Allied personnel were successfully evacuated from France.

On 16 June, French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned when he became convinced that he no longer had the support of his ministers, and his cabinet had reacted angrily to a British proposal that France and Britain unite to avoid surrender. Reynaud was succeeded by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Pétain promptly addressed the people of France to announce that he intended to ask the Germans for an armistice.

Germany’s humiliating defeat in the First World War had been consumated on a railway carriage in the Compiégne Forest in 1918. Hitler chose to have the signing of this new armistice in the same rail car. He would even sit in the same chair in which Marshal Ferdinand Foch had sat when watching the defeated German representative sign at the end of WWI. France capitulated on 25 June 1940.

With the German occupation, France became a divided nation. The Germans held the north and west of the country, and a so-called independent state, Vichy France, was located in the south. From his new London headquarters following the surrender of France, Charles de Gaulle, who had been made Undersecretary of National Defence by Paul Reynaud, declined to recognize the Vichy government of Marshal Pétain and set about organizing the Free French Forces.

The French Admiral Francois Darlan had promised the British government that he would not let the French fleet based in Toulon become part of the German fleet, but the British did not trust the promise, concerned that the Germans would simply seize the fleet, then docked at Toulon and at Mers-el-Kébir in what was then French Algeria, and use it in an invasion of Britain, which Hitler would soon call Operation Sea Lion. On 3 July, a British naval force bombarded the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir, sinking a battleship, damaging five other vessels, and killing nearly 1,300 French servicemen. The British needed military aid and financial assistance from the United States and the attack on the French fleet was also meant to show the U.S. that Britain intended to continue the war with Germany despite the French capitulation. In 1942, when the Germans tried to take control of the French fleet in Toulon, the French crews scuttled the warships—this, after Churchill had ordered that the French fleet either join forces with the Royal Navy or be neutralized somehow to prevent it from falling into German or Italian hands.

With Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of northwestern Africa in November 1942, the Germans moved to safeguard southern France by occupying the Vichy state. Among the most significant events of the war was the Allied invasion of the European continent on 6 June 1944, the D-Day landings at Normandy, leading to the liberation of France. By then, more than 580,000 French people had been killed, of whom 92,000 were military personnel. It is believed that upwards of 49,000 Germans were killed in the offensive for France and in the occupation period. British casualties have been estimated at about 68,100 killed, wounded or missing. By August 1940, more than 1.5 million Allied military personnel had become prisoners of war of the Germans.