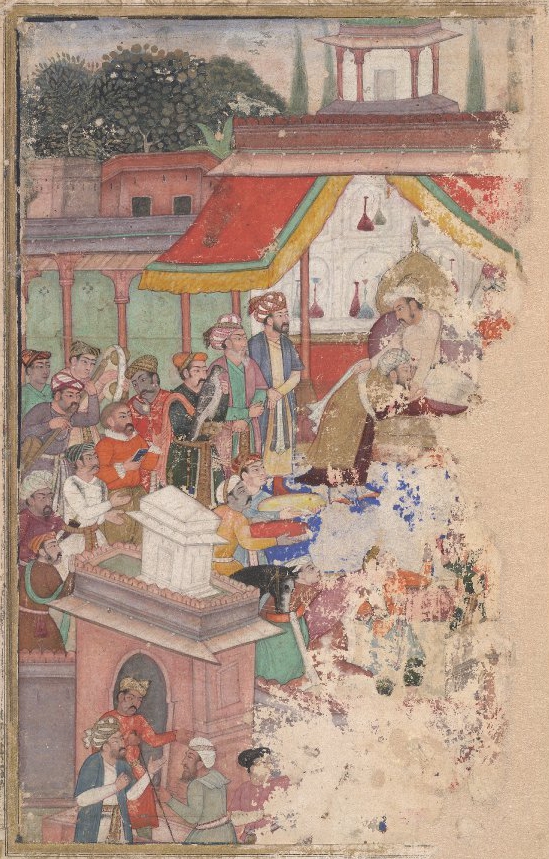

Jahangir investing a courtier with a robe of honour watched by Sir Thomas Roe, English ambassador to the court of Jahangir at Agra from 1615–18, and others.

The constitutional basis of a British military presence in India lay with the grant in 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I of a Charter to the Company of Merchants of London trading to the East Indies. This Company was granted the monopoly of all trade between England and all lands from the Cape of Good Hope as far east as Cape Horn, except for any place in the possession of a Christian prince, whose own subjects might trade with England as he wished. The monopoly was not, however, intended to be in restraint of trade, but to promote and regulate it and to provide for its protection by arms if necessary. The purpose of arrangements which placed trade in the hands of a particular group was to ensure the exclusion of individuals who, in search of a quick profit, might alienate local authorities on whose goodwill a regular prosperous trading system depended. A company which held the monopoly could be relied upon to govern the activities of its members and servants with a view to the long-term interests of itself and the nation of which it became, in its chartered area, the representative. It was hoped that a body of merchants, who generally speaking find peace more profitable than war, would be particularly anxious to avoid occasions of dispute. On the other hand, as the East Indies were a vast area, a year away from orders or help from home, the East India Company was empowered to arm its ships and servants for their own protection and to make laws, not repugnant to the laws of England, for their regulation.

The constitutional right to establish trading stations or ‘factories’, where their local factors would do any necessary business between the arrival of one annual voyage and the next, and to fortify or garrison them, was also dependent upon individual charters granted by the rulers in whose domains these lay. The first such station on the subcontinent of South Asia was established on the west coast, at Surat, by authority of a grant from the Mughal Governor of Gujerat. On the east coast a factory was set up at Masulipatam around 1620 and the Company’s first fortifications were built at Armagaon in 1625. The first grant of land with the right to construct defence works and collect revenue was made in August 1639, when the Company’s factor on the Coromandel coast obtained a grant from the local representative of the Raja of Chandragiri. This monarch, the vestigial successor of the Hindu empire of Vijayanagar (destroyed by the Sultanates of southern India after the battle of Talikota in 1565), thus played his part in the foundation of a new empire that would become paramount in India. The fort, named in honour of England’s patron saint, and built–despite the objections of the East India Company’s home authorities to the financial implications–was Fort St George, the official title of what subsequently became the Presidency of Madras.

In 1661 the Portuguese settlement at Bombay was ceded to the English Crown as part of the dowry of Charles II’s queen, Catherine of Braganza. A battalion of 400 troops, the first element of the British Army to serve in India, was sent to take possession but, as a result of opposition by the local Portuguese officials and a refusal by the Mughal authorities to allow it to disembark at Surat, it did not succeed in doing so until 1665, having lost seventy-five per cent of its numbers to tropical or other illnesses. Reinforcements were subsequently sent and the whole garrison, together with the rest of the Bombay establishment, was handed over by Charles II to the East India Company in 1669.

The charter granted to the Company by Charles II on his restoration in 1661 took account of the existence of permanent British possessions in India. It empowered the Company to maintain warships as well as the armed East Indiamen which it chartered and to recruit men as regular soldiers, with whom it could lawfully make war against any non-Christian prince. When the charter was renewed in 1683, the Company’s right to maintain local fleets and armies, subject to ultimate Royal authority over their employment, was further confirmed. It was with forces raised under the provisions of this charter that the Company began its first war against an Indian power, a campaign in 1688–90 against the government of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

The charter of 1661 established the London East India Company as a permanent joint stock corporation. Major stockholders could summon and vote in a General Court, which determined Company policy and appointed an executive body made up of twenty-four committee men, headed by an elected Governor and Deputy Governor. The same charter empowered the Company to appoint governors and councils to rule over its major settlements and execute the directions they received from their masters in London. Their right to exercise martial law was specified in the charter of 1669 handing over Bombay to the Company, and extended in that of 1683, which authorised the Company’s governors and factors to ‘execute and use within the said Plantations, Forts and Places, the Law called the Martial Law, for the defence of the said Forts, Places, and Plantations, against any foreign Invasion, or domestic Insurrection or Rebellion’. By granting this right to the Company, the Crown recognised that the Company’s holdings in India had become rich enough and large enough to attract military threat and merit military defence.

The East India Company’s first regular troops were those taken over, with Bombay itself, from the Crown in 1669. Most of the original contingent of royal troops which had landed four years previously had succumbed to the effects of the climate, drink and disease, but replacement drafts from England and locally recruited mercenaries of European descent (mostly Portuguese with a few Frenchmen) gave the East India Company a Bombay Regiment of two companies and a total strength of five officers, 139 European other ranks, and fifty-four Indian Christians or ‘topasses’ so-named from the Persian word ‘top’ or gun. An additional company under command of Captain Shaxton arrived in 1671 and Shaxton was appointed by Governor Aungier to be a member of the Bombay Council and Deputy Governor. It was to this company that three years later fell the unenviable distinction of committing the first of the numerous acts of mutiny that disfigure the record of British arms in India. As with so many mutinies, the grievance was a financial one, the troops objecting to the losses they suffered when their notional pay was exchanged into local currency, and to what they did receive being further diminished by stoppages to pay for their uniforms. One mutineer was hanged, Shaxton was sent back to England and Aungier was ordered that in future his Council should be drawn only from the Company’s factors, not its military servants. The Council of the Company’s settlement at Surat, to which Bombay was subordinate, recorded its view that soldiers were a ‘querulous ungrateful people, and never satisfied’.

After the Glorious Revolution of 1688 the East India Company, which had been patronised by James II, received little sympathy from William III or the Whig majority in Parliament and the latter resolved in 1691 that a new East India Company should be founded. Lavish bribes by its own directors secured a fresh charter for the original or London Company in 1693 but the new Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies was itself granted a charter in 1698. These disputes in England led to difficulties in India, where the Mughal authorities found it difficult to distinguish between two sets of English merchants, each traducing the other as thieves and pirates. In November 1701 Aurangzeb placed an embargo on trade with both of them and on all other European companies, pending the payment of compensation for losses inflicted by pirates and the provision of anti-piracy patrols. In a compromise effected in 1702 by Lord Godolphin, the two rival East India Companies were combined into a single body, known from 1709 until 1833 as The United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies. This company inherited the powers of both its predecessors in England and India. Its government was vested in a Court of twenty-four Directors, including a Chairman and Deputy Chairman, generally referred to as ‘The Chairs’, to be elected by the General Court composed of major holders or ‘proprietors’ of the Company’s stock. The Directors were also empowered, according to the English Company’s charter of 1698, to appoint and remove governors and officers and to ‘raise, train, and muster such military forces as shall or may be necessary’ for the defence of their forts and factories. In India, the Company legitimised its position by obtaining a charter or farman in 1716 from the Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar, a great-grandson of Aurangzeb, and the third emperor to come to the throne since the latter’s death nine years earlier.