The war on terror began to unravel the Strategic Defence Review of 1998, which besides the usual rationalization and economies was also motivated by achieving a reinvigorated joint expeditionary edge for Britain’s armed forces. Much of this was brought about by the long-term land commitments in the Middle East since 2001 and the subsequent return to Afghanistan in 2005, which although expeditionary in nature were not what were expected or anticipated in 1998. Certainly they cannot be held up as the joint (and hoped-for) naval-dominated operations espoused by the Strategic Defence Review and the Royal Navy at the end of the twentieth century; instead they have become increasingly land centric in orientation and perception, if not in reality. Worse still were the cuts imposed on the Navy in order to free up funds for the wars themselves, most notably in Afghanistan since 2001. These have seen surface ships, from hydrographic vessels such as HMS Roebuck to aircraft carriers such as HMS Ark Royal, being retired prematurely to pay for the deployments. Additionally, critical platforms such as the Sea Harrier in 2006 and the Harrier GR9/9A fleet in 2010 have retired, together with deep cuts in the numbers of escorts, mine-warfare vessels and fleet auxiliaries. Personnel levels have likewise continued to fall, declining to 30,000 by 2015. The final large-scale cuts to release money for the war in Afghanistan came with the Strategic Defence and Security Review of October 2010.

The shift in strategic posture began earlier with reviews in 2002 and 2004 attempting to keep the 1998 Strategic Defence Review on track but seeing the course for the rest of the decade laid down; Iraq and Afghanistan were paramount. Any medium- or long-term plans and procurement would have to wait, especially for funding. Politically the Royal Navy has also had to face constant internal political challenges from a series of British prime ministers. Tony Blair, a supporter and employer of naval power, was replaced by Gordon Brown who understood the industrial arguments but not the strategic employment benefits of navies. Labour was then replaced by the Conservative-dominated coalition government, with the resulting defence review of David Cameron’s administration appearing to sympathize with the arguments of the RAF rather than those of the Navy in 2010.

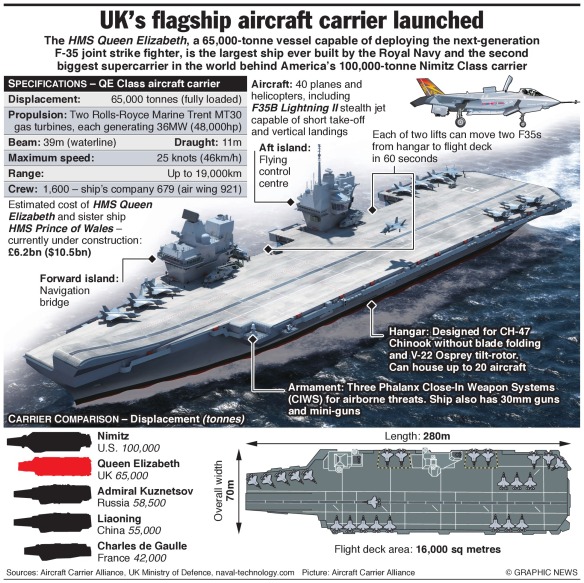

Procurement has also provided challenges. The 1998 review had laid out long-term procurement up to 2015 with the year-long review being properly funded for future expenditure. Unfortunately two major wars and a number of procurement cost overruns began to derail the 1998 plans. British involvement in Afghanistan had cost over £17 billion alone by the start of 2012. Naval procurement programmes also caused concerns. The Queen Elizabeth carriers doubled from the initial £2.3 billion to over £5 billion. Astute class submarines suffered serious delays and increases in cost, with American technical help eventually required to bring the programme back on track. while the Type 45 destroyer programme, although not going above its intended budget, resulted in only six ships being built as opposed to the 12 initially envisaged. However, these seem insignificant when compared with other procurement projects such as the RAF’s Eurofighter Typhoon, which became an ever widening abyss that had easily surpassed £20 billion in research, development and production costs by 2010 and is expected to cost over £37 billion for the lifetime of the programme and will only result in just over 100 aircraft entering British service. Delays and cost overruns also seriously affected the Nimrod update, with some £4 billion being expended for eventually nine aircraft (none of which entered service), and the Future Strategic Tanker programme which will see £13 billion being spent for just 14 aircraft.

The 2010 general election provided a platform to carry out a more far-reaching defence assessment and this came in the form of the Strategic Defence and Security Review of October 2010. Unlike the 1998 review, which had taken a year to formulate, the new review only took some three months, which naturally brought some criticism. Most critics, however, waited for the findings. At the time, the review detailed cuts for all three services but provided the least comfort to the Royal Navy, for although the RAF lost aircraft and squadrons they were mostly maritime in flavour and not what was regarded as their core role of land-based attack operations. This supported contentions that the RAF and the outgoing Chief of the Defence Staff sacrificed the inherently flexible Harrier community to safeguard their Tornado force. Cuts to the Royal Navy included the early retirement of the last four Type 22 frigates (with the escort force dropping to 19 vessels), the carrier HMS Ark Royal, the whole of the recently updated Joint Harrier fleet, three fleet auxiliaries (with the sale of another) and the end of the Nimrod programme. Britain was going to take another assessed risk that it did not need fixed-wing capability at sea until the future carriers and their Joint Strike Fighters entered service from the middle of the decade. The gap left by Nimrod would be filled by utilizing existing air assets such as the already stretched Navy Merlins.

Libya and the future

But as is often the case the findings of the 2010 review were not borne out by events, as the Arab Spring in North Africa showed. Less than six months later Britain found itself co-leading with France another coalition effort to initially protect Libyan refugees and then isolate and neutralize the Libyan government of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. This soon became a NATO-orchestrated mission known as Operation Unified Protector. Whilst French, American Marine Corps and Italian firepower predominantly came from the flightdecks of carriers – the two latter nations employing Harriers – Britain was forced to employ costly, time-consuming and slow-responding land-based aircraft on missions to support the coalition’s objectives. Over 3,000 sorties were flown by the RAF that resulted in 600 targets being attacked, whereas French naval aircraft from their carrier Charles de Gaulle flew over 1,500 sorties resulting in 785 ground-attack missions.

More successfully, and again demonstrating the flexibility of naval power, the Royal Navy carried out humanitarian and evacuation actions, mine clearance, embargo and blockade duties, key naval gunfire support work, further Tomahawk strikes, ground surveillance and target direction with ASaC 7 Sea Kings. The naval task force also employed five AAC Apaches from HMS Ocean, which in their 22 sorties managed to destroy 100 targets – one-sixth of the RAF’s total for a fraction of the effort.

The Royal Navy’s acquisition programme after Libya has remained mostly on track with the aim of seeing the first future carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, operational by the end of the decade. There will also be a totally rejuvenated Fleet Air Arm compared with that of 2010, new escort vessels of the Type 26 class with new land-attack missiles, smaller modular warships that should replace existing mine warfare, offshore patrol and hydrographic vessels as well as new RFA vessels such as the four Tide class 37,000-ton support tankers ordered in 2012. The Type 45 destroyers should also be on course for Britain’s first ballistic missile defence capability. And the submarine service will have received its seven Astute class submarines as well, finalizing the designs of the successor to the Vanguard class. Thus should the plans of the second decade of this century become reality; the Royal Navy of the third decade will be more powerful and capable of global deployments in a way not seen in anyone’s lifetime to date, being at the forefront of both Britain’s offensive and defensive weapons systems.

The Royal Navy started the twenty-first century in a very different shape to that at the start of the twentieth century – far, far smaller in terms of manpower and ships, with just a handful of overseas bases and a political and public profile probably smaller than for centuries. Yet the naval service in the intervening 100 years had grown to unbelievable sizes, reaching almost a million personnel before returning to a strength more akin to the age of sail. It had successfully implemented a myriad of roles and commitments, fought the greatest wars in history and time and again helped to create the conditions for victory in all of them. It had successfully fought under, on and over the world’s waters as well as on lands around the world, as well as being a key player in Britain’s global commitments, especially the Western alliance. Levels of technology had surpassed comprehension and the ability to influence the world’s land mass and the world’s populations had achieved new heights. In the twenty-first century the Royal Navy has the ability to reach with conventional weapons the bulk of the world and with nuclear weapons the whole of it in a way that it could not have envisaged in the age of the dreadnought.

More importantly a number of key roles for Britain’s security are performed purely by naval power – anti-piracy, countering maritime terrorism, fishery and economic resource protection and anti-drug interdiction being some, arguably below the threshold of war. In wartime, naval power has at times been either the dominant or the only military force able to be employed by Britain. This could well be a situation that continues into the future. In fact governments on both sides of the Atlantic have made clear in the second decade of this century that land-based wars will now be avoided. The flexibility that naval power brings will allow nations to have a global footprint without enduring physical land-based commitments. Neither should the economic drivers of the international system be overlooked. The process of globalization that began hundreds of years ago on the back of wooden sailing ships continues into the twenty-first century. Global trade is seaborne, British trade is seaborne, Britain’s trade is global. Therefore there will always be a requirement to keep the global highway stable, and today Britain’s only asset to accomplish this is, as it has been for centuries, the Royal Navy.