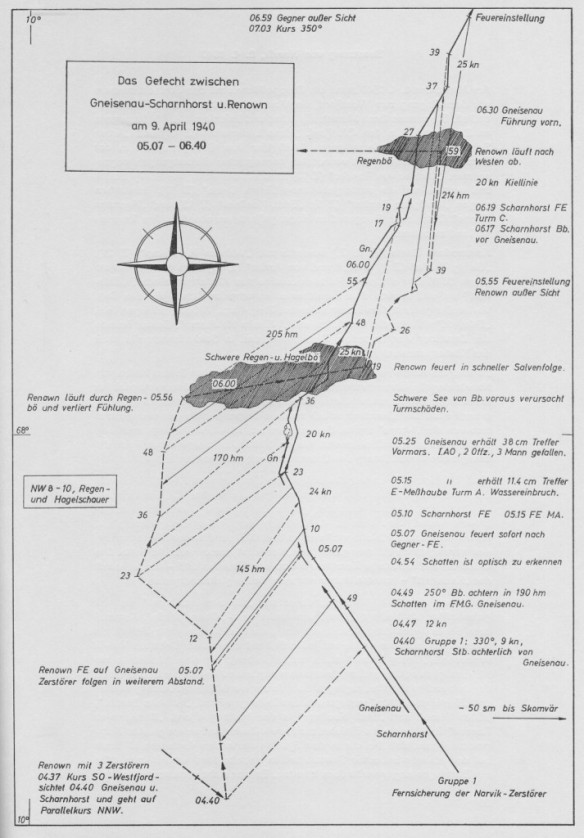

Renown maintained her course for ten minutes and then altered course to 080° and increased speed to 15 knots and, soon after, to twenty knots. At 03.59 she hauled right round to 305° so that she was roughly parallel to the enemy, with her A arcs just open. At 04.05 when she was just abaft the beam of the leading German ship, Renown opened fire at a range of 18,600 yards.

At 04.11 the Gneisenau returned the fire. She had not fired earlier having still failed positively to identify the British ships as enemy between 03.50 and 04.00. Scharnhorst in fact did not sight the Renown until she actually opened fire. Both the German ships concentrated their fire at Renown for the next ten minutes or so, while Renown for her part concentrated her main armament on Gneisenau and her 4.5-inch batteries on Scharnhorst, for all the good they could have done against her thickly armoured hide. The destroyers also opened fire with their 4.7-inch guns although at the sort of range at which the engagement was being conducted these weapons can hardly have been effective other than in impressing the enemy with their determination to fight.

On Renown’s bridge, young signal boy Herbert recalled that little could be seen of the enemy other than their gun flashes. ‘The visibility was very poor and everything was confusing at the offset; it was thought that we were engaging the Hipper in the beginning, and as we could only see the outline of the ships when they fired their salvos, this is understandable.’

Fighting the guns in such conditions was no sinecure either. John Shattock, RM, recalls his experiences during the battle thus:

I was in B turret shell room which was the lowest chamber of the turret; above are the magazines containing the cordite charges and above these the 15-inch Gunhouse. In the shell room the huge 15-inch shells were stowed in big bins and by the means of an overall hydraulic system and very large ‘grabs’ we had to hoist out the shells from these bins and transport them to the ‘trunk’ of the turret which contained the hoist lift up to the gun house.

As you can imagine in the terrible weather, the ship was rolling and pitching and we were being thrown about. It was hard work controlling the shells on the grab, which was suspended by wires from the track in the deck head. In the meantime during the chase the ship was ploughing into very high seas, and consequently the turret was shipping quite a lot every time the breeches of the guns were opened. I believe that A turret being lower, got more of this than we did.

In addition to this the stench of cordite blowing down the hoist was uncomfortable in the extreme.

In conventional ships X turret was the Marine turret but in the three-mounting Renown they usually manned B or Y.

Further down in the great ship as she raced through the gale in pursuit were Bill Kennelly and his ‘DB’ party. Of course they did not see anything but felt the guns roaring through the ship and the smashing effect of the great seas as Renown tore along.

We were closed up and nattering quietly when the Intercom crackled and – ‘This is the Captain speaking. Two unidentified warships have been sighted and we are closing’. Next came: ‘We are about to open fire and ship will increase to full speed.’ The weather of course was, as usual, lousy, very heavy seas and snow squalls. We left our destroyer escorts far behind as they couldn’t cope with the seas and in every sense it was all ours.

Renown was hit twice without serious damage. A.V. Herbert recalls:

The most vivid memory of that morning is as they fired the first few salvos one of the 11-inch shells went clean through our foremast around which of course the Renown’s flag deck and bridge were built. That mast remained standing through all the squally weather, and was eventually I think, cut and the piece containing the hole made by the shell placed in the museum at HMS Drake, barracks at Plymouth.

Henry Shannon remembers:

They had two remarkable hits on us, one 11-inch shell passed through Renown just above the water line aft and went out through the other side without bursting. One compartment was flooded through this hit and one engine room rating was trapped in the compartment underneath. Damage control was of a high standard and the compartment was watertight. He was rescued later after the action when the holes were blocked and the upper compartment pumped out.

The second hit went through our foremast right in line with the 15-inch and 4.5-inch spotting tops, they sure knew what they were aiming for. That shell carried away the main wireless aerial so we were out of touch with the Admiralty for a while, but it was repaired during the action by the wireless officer; he was decorated for this deed later, and well deserved it. We didn’t have a single casualty on Renown but our own fire from the forward 15-inch guns shook the rivets so much off our starboard bulge forward that 30 feet of it stuck out at the angle of 90° and this caused a terrible, second, bow wave. Our forward messdeck was flooded but the damage control party again pumped it out and erected a false bulkhead, which did the job for a time.

Bill Kennelly was busily employed as a result of this damage.

One shell drilled a hole in our mainmast, the second clipped the funnel, while the third penetrated close aft of Y magazine, into and out through the bottom of the Admiral’s wine store. Never have I seen so many volunteers to help the DB party pump out the compartment, all arriving with their suck-sacks, tool-bags and what have you and all subsequently gliding away forrard with their loot! I don’t know how the Admiral managed for wine but we all did very well thank you, our DB section looked more like an off-licence. We returned to Rosyth later amidst a lot of bull, all good for morale, but it would appear that the sea had damaged us more than the enemy, umpteen feet of our bulges had torn off on both sides, and resembled giant scoops.

Captain A.W. Gray was just about the oldest-established member of Renown’s crew at that time, having stood by her since September 1937 as commander in charge of the engineering department, and he was indeed her only officer during her first year of reconstruction, until July 1938 when other specialist officers were appointed. He had supervised the installation of her new machinery and tended it with care and affection ever since. Now those engines, his pride and joy, were working flat out driving the great ship through the heavy seas in full pursuit of the flying enemy. If any doubts were felt about the performance of the old veteran with her new heart, this action dispelled them. Indeed it was not her engines that caused her to ease up, but the effect of her speed on her firing – as Captain Gray later explained:

Renown had to maintain a maximum speed of 24 knots to avoid the two foremost turrets being submerged by the high seas; it was found that when she had worked up to steam at 28 knots it was impossible in those conditions for the turrets to fire.

The major hit Renown received aft passed through the gunroom bathroom starboard side and out of the port side above the waterline without bursting. This was fortunate as it was above the steering compartment and rudder head.

But if Renown took slight punishment, she was more than equally dishing it out as well. Despite the conditions the two forward turrets performed magnificently. At 04.17 the Gneisenau received a hit on her foretop at a range of 14,600 yards and this destroyed the main fire control equipment and temporarily disabled her main armament. At 04.18, with no means of usefully using her main armament, the German battle-cruiser, using her secondary armament, turned to a new course of 030° with the obvious intention of breaking off the action. To cover her consort, the Scharnhorst crossed the stern of the Gneisenau and made smoke.

Renown then turned northwards and concentrated all her fire on Scharnhorst. For an hour and a half until 06.00, there ensued a chase to windward. Weather conditions were deteriorating with a heavy swell and great seas due to the rising velocity of the wind, which shifted from north-north-west to north-north-east.

The destroyer screen soon found that conditions were so bad that they could not keep up with the Renown and gradually they fell back. The Renown continued to engage the Scharnhorst but no hits were observed or recorded. Both German ships continued to fire at the British battle-cruiser – the Gneisenau used her after turret and the Scharnhorst yawed from time to time to fire a full broadside.

At 04.34 the Gneisenau suffered a further hit being struck on A turret near to the left hood of the rangefinder. The watertight hood was wrecked and flooding of the turret put it out of action. She was hit for the third time shortly afterwards on the after anti-aircraft gun on the port side of the platform but suffered only minor damage as a result.

Just before 05.00 the two German ships vanished into a rain squall. Early on in the engagement, the Renown had increased to full speed but after the turn northwards, she had to reduce speed to 23 knots and then to 20 knots; at that speed Renown barely held the range. This, as we have seen, was in order to keep her guns firing forward; the Germans firing astern were not so affected of course and could hold their higher speed, thus gradually increasing the range.

When the German ships disappeared from sight, the Renown turned on to an easterly course and again increased speed to 25 knots; but at about 05.20 when the weather cleared and the German ships were again in sight, they had further increased the range. The Renown turned once again to bring the enemy fine on her bows and opened fire once again. No results were observed and both sides persistently altered course to avoid the fall of shot.

Further squalls of sleet and rain obscured the target and although Renown achieved a speed of 29 knots for a few minutes she could not gain on the German ships and they were last observed at about 06.15 at which time they were well out of range of Renown’s main armament.

Renown maintained her northerly course until about 08.00 and she then turned westward so that she would be in a position to intercept the German ships again should they alter course and attempt to break back to the south and home. No further contact resulted however, and we now know that Lutjens sped at top speed away to the north and then turned due west to the south of Jan Mayen island at noon next day, before making a hesitant foray south-east of the Faeroes on the 11th, awaiting bad weather in which to make his dash for safety. The Home Fleet cast north for him close in to the Norwegian coast but as they searched north-east Lutjens, concealed by poor visibility, slipped past to the west during the night of the 11th/12th and made good his escape.