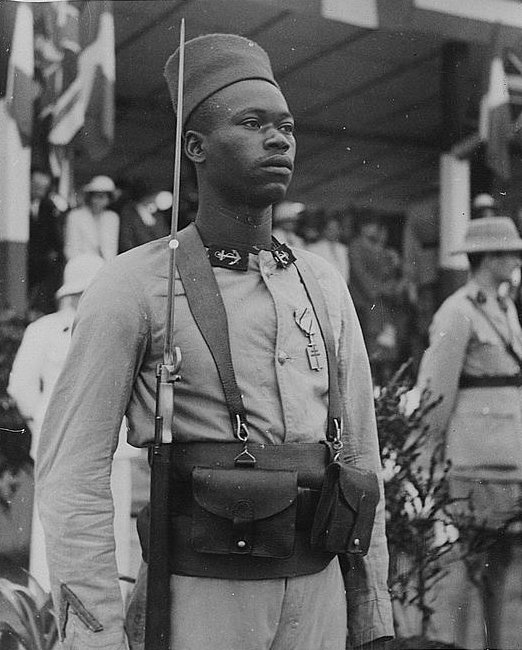

1942, Brazzaville, French Equatorial Africa. A tirailleur who has been awarded the Cross of Liberation by General Charles de Gaulle.

After a long and demoralizing wait during the so-called Phony War (September 3, 1939 to May 9, 1940), several North African divisions saw fierce combat with the German army during its initial breakthrough in the Ardennes region. In Southern Belgium and along the French border with Luxembourg, North African troops, including some Spahi cavalry, fought courageously but to no avail. The remainders of some of these units were evacuated from Dunkirk and later sent back to France for deployment in the final battles in Central France. Units of tirailleurs sénégalais also participated in some of the initial battles in May, but most of them experienced their hardest test during the second phase of the German offensive (Operation Red) starting with the attack on French positions along the Somme River on 5 June. In many cases, tirailleurs sénégalais put up desperate resistance in hopeless situations until the end of the fighting two and a half weeks later. German officers ordered executions of 1,500 to 3,000 captured black soldiers, and an unknown number of black soldiers were killed in battles in which the German forces had decided not to take any black prisoners or en route to prisoner of war camps. North Africans were generally spared, although in some cases German units considered them black soldiers and also massacred them.

A little appreciated fact of World War II history is that the Free French forces, under the command of General Charles de Gaulle, for a long time consisted predominantly of African soldiers. De Gaulle ’ s first territorial base was Chad in French Central Africa, which rallied to him officially in August 1940; henceforth, African soldiers from Central Africa complemented the nucleus of French forces that had fled to Britain in the wake of the defeat of 1940. Migrants from French West Africa, who crossed the border to the British colony Gold Coast (today Ghana), strengthened the Free French regiments in 1941–1942. When the British and Free French invaded the French Levant in June 1941, Africans under Vichy command fought against Africans under Gaullist command. After the success of the invasion, some of the former agreed to join the Free French forces, while others demanded to be sent back to France or French North Africa. The Allied landings in North Africa (Operation Torch) in November 1942 opened up new sources of recruitment. North African troops and tirailleurs sénégalais under Free French officers participated in the last battles with Axis troops in Tunisia and later in the Allied campaigns in Italy (including the battle of Monte Cassino), Southern France, and Germany. Even the Free French forces landing in Normandy several weeks after D-day included some African troops.

In early 1943, the French forces fighting on the side of the Allies still had a majority of Africans. They included approximately 100,000 tirailleurs sénégalais and 405,000 men in the North African units, of which 230,000 were “indigenous” North Africans (Clayton 1988 , p. 143). Once parts of France were liberated, more and more white French men, many of whom had belonged to the resistance, streamed into the French forces hamstrung by severe shortages of equipment ranging from uniforms to weapons and tanks. The shortage of American-supplied materiel imposed a cap on French troops and thus precluded a large-scale integration of white French recruits without the dismissal of other troops. In fall 1944, de Gaulle therefore decided to withdraw the Black African and some North African troops from the frontlines and to replace them with white French men. This decision, called blanchiment (whitening), was perceived by many Africans as a deliberate snub, as if they were not worthy of completing the imminent victory by advancing into Germany. The motives for the blanchiment were certainly complex. A careful case study of this question is Gilles Aubagnac, “Le retrait des troupes noires de la 1ère Armée” (1993), which argues that the official reason (the cold climate) was not the only motive and that political and psychological considerations also played a role. Whereas Aubagnac at least gives credit to the official reason, Echenberg and Mabon see it as a cynical pretext, and Lawler takes a slightly different position by showing that some West Africans did appreciate being allowed to leave the front in harsh climatic conditions. To be sure, it had been customary in both world wars to withdraw the troops from tropical Africa to the South of France during the winter months because they were believed to be more vulnerable to the diseases prevalent in the cold and wet conditions in northeastern France; this had happened for the last time in 1939–1940, and the new French army could argue that it was continuing this practice. Yet there were other motives as well. De Gaulle was worried about the strong communist orientation of many armed resistance groups and wanted to tie them into his military hierarchy to better control them. He may also have wanted to demonstrate to the other Allies that France could make a powerful contribution to the war through its own manpower, not through units recruited in Africa. It is also likely that fears of provoking hostility in the southwest German territories, which France wanted to control after the war, played a role: a new “black horror” campaign might arise in reaction to an invasion by black troops.

The mindset of many French politicians and military leaders at the time of the blanchiment suggests that all of these reasons played a role; French officers were greatly worried about the claims and aspirations of African soldiers who had tasted victory in Europe and who sometimes bolstered their claims by arguing that they had fought harder and longer than most white French troops. The French colonial administration, shaken by the economic and administrative consequences of the French defeat in 1940 and the rift between Vichy and de Gaulle, wanted to readapt African soldiers quickly to the colonial routine. Downplaying the contribution of Africans in the liberation of France was a central concern – and not only of the French authorities, as Olivier Wieviorka has shown in Normandy: The Landings to the Liberation of Paris (2008), where he mentions an Anglo- American intervention, supported by the Free French, to exclude black French troops from the liberation of Paris.

The French efforts to restore the colonial order without too many concessions clashed with the frustrations of African veterans. Short of funds and shipping, the provisional French government kept most former POWs – as well as African troops released through the blanchiment – in large repatriation camps. Some former POWs found themselves in the same camps as they had been under the Germans, but often under worse conditions. Frustrated by years of captivity, a long wait for repatriation, and withheld pay, former POWs met embittered soldiers affected by the blanchiment . The mood of the veterans was explosive, and explode it did on many occasions. The most fatal case was a mutiny by tirailleurs sénégalais , all former POWs, in the camp of Thiaroye near Dakar on December 1, 1944. Tired of broken promises regarding their pay, the veterans refused orders to board trains and demanded to be paid in the camp. French army and police units (many of them also consisting of tirailleurs sénégalais ) gathered to repress the mutiny, opened fire, and killed 35 veterans. Not much later, North and West African veterans in Versailles, demanding the release of arrested comrades, stormed the local police station and took policemen as hostages. After a firefight between the veterans and the police, the French authorities fulfilled the demands of the veterans and sent them to Africa on the next ship. More riots followed, as African soldiers returned from German captivity in the spring and summer of 1945. In Saint Raphaël on the Mediterranean coast, veterans disgruntled about the poor conditions in the camps took to the streets and confronted the police in August 1945; four people were killed and many more were wounded. French authorities habitually blamed these disturbances on German propaganda and the influence of American anticolonialism.

The returning African veterans often found their homelands profoundly trans- formed. In Algeria, unrest had been smoldering in several cities during the last years of the war, and it erupted in Sétif in an extremely violent confrontation on May 8, 1945. In Morocco and Tunisia, as well as in sub-Saharan Africa, movements for political emancipation and independence had grown despite repression by the Vichy governors and their successors. Veterans brought their own frustrations with the French administration (both Vichy and Free French) to the mix. Nazi Germany, with its racism and discrimination, had been defeated and discredited, and French African soldiers often looked up to the ideals of democracy and equality upheld by the United States, hoping that they would reform or overturn the colonial system. Nevertheless, not all veterans immediately supported independence. Not without some success, the French government adapted colonial legislation and built up a support system and social network for veterans, casting them as representatives of France and as mediators between the colonial administration and the local people. Members of the independence movements sometimes treated veterans with suspicion because they had fought for the “wrong” side. In the long run, however, French reforms and promises could not keep up with the grown aspirations of the locals, including the veterans. Veterans, hoping for privileged access to jobs and services, saw their pensions frozen by the French state at the time of national independence, and the struggle to “de-crystallize” pensions has succeeded only in the period 2006–2010.