When war broke out in 1939 no one was ready – not the British, not the French, not even the Germans. The Nazis, indeed, were still trying audaciously to build a continental empire on which to base an industrial and military structure that would ensure their world dominance. It was an exercise in deadly brinkmanship they hoped would carry them through at least to the mid-1940s before they would have to meet enemies of substance. But like a piece of scorched paper on a smouldering fire, the world was suddenly ablaze.

The guns of France had been silent for only 21 years when the fighting began. Quartermasters’ stores throughout the world had the left-overs prudently stacked away in grease and naptha, and many of those who fought in 1914–18 were on hand to provide the leadership and tactical thinking for the new generation of soldiers, most of whom had been born either during or after the last struggle. It wasn’t quite just a matter of unpacking, reissuing and starting all over again, but Britain and Germany entered the new war with predominantly infantry armies whose pudding basin helmets on the one side and coal scuttle helmets on the other created a sense of déjà vu.

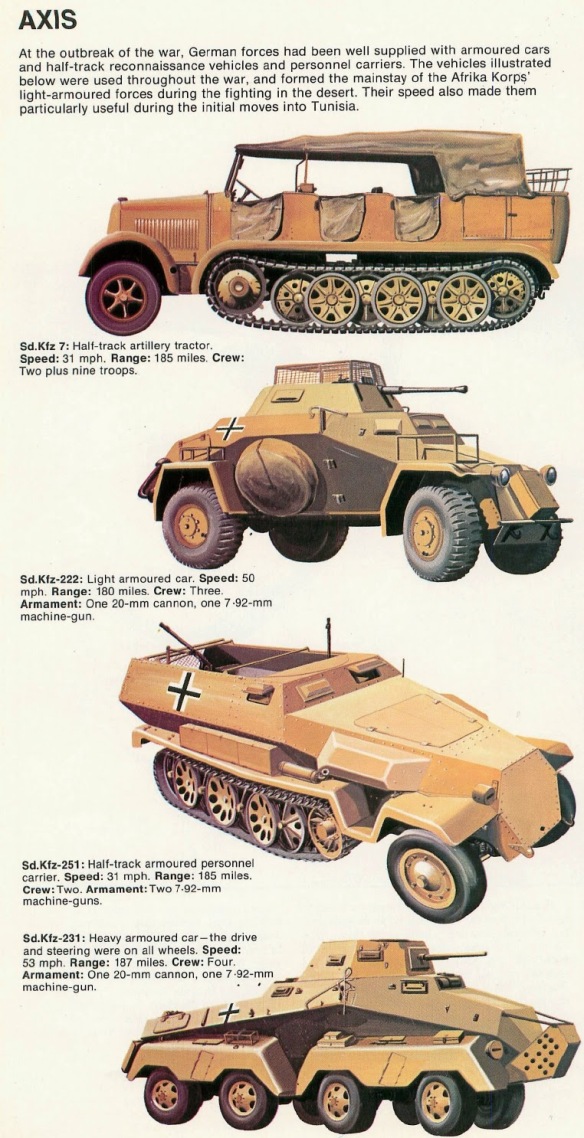

Surface appearances, however, were illusory. The harvest of the machine-gun, scything stumbling infantry in Flanders, had led to a resolve to combine fire power with mobility, and the new armies used wheels, tracks and wings. The Germans had the lead, at least until July 1942. Their panzer divisions gave a cutting edge to attack, and their dive bombers, vaulting over land barriers, were overhead artillery, combining pinpoint accuracy with intimidating sound. For their part the British fumbled with innovation, at least until El Alamein in July 1942, after which American tanks and bigger and better anti-tank guns began to swing the balance.

The base line for these novelties remained the infantryman, the soldier with a rifle. And despite all the technological innovations that, in the Desert especially, changed the face of warfare, the primitive gleaming steel of the bayonet retained its place, a symbol, in a way, of the dehumanizing brutality of war. Though the shell and bomb might wreak greater havoc and inflict more horrendous injuries, the bayonet required one man to confront another, face to face, and thrust a blade into his body, and to prepare him for this the army indulged in bayonet practice in which inoffensive straw dummies were attacked with great ferocity and manic shouts.

The whole range of infantry equipment, with rifles, machine-guns, mortars and artillery, tended to perpetuate an infantry structure similar to that of the First World War, despite a number of changes, and it was this rigidity that both sides sought to reshape in the Desert, where marching columns of old fashioned infantry were as anachronistic as the Mary Rose would have been at the Coral Sea. Of course motor transport for troops was now supplied in greater numbers, and in the Desert the effectiveness of the infantry depended on there being capacity for everyone to be carried on wheels, and when motor trucks were lacking, commanders sought to trim down their infantry forces to the number that could be carried. This was yet another factor to impact on what happened at Alamein in July. Essentially, on a battlefield where mobility was critical, the soldier on foot was a helpless pedestrian in a stampede of bulk.

Barbed wire was of little consequence in the Desert, but the minefields it surrounded were. Mines became significant from Gazala on, and at El Alamein in particular were a factor in determining success or failure in attack. As the main emphasis in sewing minefields was to put up a barrier to vehicles, infantry could usually pass through on foot like fluid through a membrane, but tanks, guns and lorry-borne support weapons were filtered out unless a way through could be made for them. A critical element in attack therefore became the ability to clear and mark adequate lanes, and for follow-up forces to be shown where they were. And simple as this operation might sound, it was the inability of Eighth Army formations to accomplish this that led to disaster. At Alamein, this passive device, lying dormant in the sand, affected the course of history and played its part in the destruction of military careers.

The aircraft and the tank brought new, or rather more efficient, weapons on to the scene to counter them. Both sides had their light, medium and heavy anti-aircraft guns. The tank also brought forth a family of infantry and artillery weapons to oppose it, and it was here that the Germans were dominant, at least until mid-1942.

The Germans had two anti-tank guns that slaughtered British tanks -the 50mm PAK (PAK is an abbreviation for the German word for anti-tank gun, as FLAK is for anti-aircraft gun, and distinguishes it from the KWK gun fitted to tanks), and the monstrous 88mm dual-purpose gun, sometimes referred to as triple purpose. The 88 is almost a beast of mythology. It was designed as an anti-aircraft gun, and proved itself to be a fearsome weapon also against tanks and infantry. It had tremendous range, something like 15 kilometres, and it has been said could kill whatever it could see. Even the Matilda, the most heavily armoured British tank, was vulnerable as far away as 3,000 metres. And because its effective range was so enormous, one or two 88s could wipe out a tank attack before the unfortunate British could bring them to within range of their puny two-pounders.

There was a British gun available that could have transformed the Desert scene and put the panzers to flight. The British had at their disposal a 3.7 inch anti-aircraft gun that could have done the same job as the German 88. It was a better gun than the 88, and it was on hand in good numbers, spending most of its time in Egypt searching an empty sky.

One embittered officer of the 57th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Major D.F. Parry, in an unpublished book written after the war called Eighth Army -Defeat and Disgrace, claimed that more than a thousand 3.7’s ‘stood silent’ in the Middle East, many never firing a shot in anger, when they could have reversed the fortunes of our armies in the field. In fact the 3.7 was used at least twice but only temporarily. In the first few days of July 1942 a battery of 3.7s, intercepted on their way to Persia, wiped off the map everything they could find, and showed how they could have redressed the balance in tank warfare. Alas, they were never used on a permanent basis, and British armoured forces suffered as a result.

The tank was the queen of the Desert battlefield. In the wide-open space of North Africa, armoured formations, with their triple qualities of mobility, protection and fire power, could overwhelm unprotected infantry, and the foot soldier could survive only if he was in partnership with his own tanks or anti-tank guns, and preferably with access to his own wheels. Rommel’s view was that North Africa ‘was the only theatre where the principles of motorised and tank warfare as they were taught theoretically before the war could be applied to the full and developed further. It was the only theatre where the pure tank battle between formations was fought … based on the principles of complete mobility.’

In the battle of the tanks the Germans were clearly the masters, at least until American Shermans were delivered as Montgomery assumed command of the Eighth Army in August 1942.

Despite his references to tank battles, Rommel saw the destruction of enemy armour primarily as a task for the anti-tank guns. His panzers were a mailed first directed at the enemy army. In full desert formation a panzer division formed a mobile box, with tanks around the outside and support and command vehicles inside. As enemy were encountered, the whole formation could, deploy for instant action, with panzers, artillery and anti-tank guns working in unison. A favourite device against British armour was the ‘sword and shield’ tactic in which the panzers flaunted themselves before the British attackers – the sword – and then retired behind a shield of anti-tank guns. They re-emerged later to clean up what was left after the anti-tank guns had done their work.

All this imposed immense strains on the command structure, and, making a virtue out of necessity, the Germans evolved a tight organisation that permitted an agile response to the changing demands of battle. And after the Gazala battles, the British press was to remark on the speed with which the Germans could make decisions, contrasting this with the sluggish reactions of British command.

The German objective was speed – to strike quickly before the enemy could gather his wits – and to this end they would sometimes ignore radio codes, permit bunching of troops and even drive at night with lights. They were not incautious, but they responded to circumstances with what seemed appropriate action rather than be bound by the book. Of course, this sometimes led to mistakes, and eventually to the stand-off at Alamein.