On 22 October, while Forrest rode north toward Johnsonville, Hood left Gadsden, heading west to find a safe place to cross the Tennessee River. The march was a miserable one. “We were cut off from our rations,” recalled one Confederate, “ragged, shoeless, hatless, and many even without blankets; the pangs of hunger and physical exhaustion were now added to our sufferings.” Hood passed up the crossing of the Tennessee at Guntersville because he claimed to lack the cavalry needed to protect his wagon train in Tennessee. He reached the Federal depot at Decatur, Alabama, on 26 October, but the garrison refused to surrender. After making a reconnaissance, he deemed the facility not worth the losses he would likely incur in a frontal assault. Hood pushed on to Tuscumbia, Alabama, where the shallows would prevent Union gunboats from contesting his crossing of the Tennessee. His weary army arrived there on the last day of October. Hood directed the army’s commissary and quartermaster officers to amass twenty days’ worth of supplies at Tuscumbia, but their efforts were hampered by a break in the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, which required a fifteen-mile trek by wagon. Worse yet, torrential rains made the roads almost impassable.

Beauregard, meanwhile, directed Hood to send Wheeler’s cavalry into Georgia to harass Sherman’s army group, and he summoned Forrest’s cavalry to join Hood’s army. But Forrest was in the middle of his Johnsonville raid when Beauregard’s message reached him on 30 October. While waiting for Forrest at Tuscumbia, Hood collected supplies for the coming campaign, and Beauregard attempted to rebuild the railroad to facilitate the effort. By the time Forrest reached the Army of Tennessee on 14 November, Hood had only seven days’ provisions on hand, far less than the twenty days’ supply he deemed essential. But he realized that time was growing short and ordered the army to cross the Tennessee River on 14–15 November. When word arrived that Sherman had begun his March to the Sea, Hood discussed the situ- ation with Beauregard and decided that an offensive into middle Tennessee was his only viable option. On 21 November, the Army of Tennessee set out from Florence, Alabama, for Nashville. Winter had come early to middle Tennessee, and the Confederate soldiers, many of them barefoot and clad in little more than rags, suffered keenly as they marched over frozen roads amid harsh winds mixed with sleet and snow.

At Nashville, meanwhile, General Thomas attempted to concentrate his forces before Hood could strike. He had about sixty thousand troops scattered throughout Kentucky and Tennessee. Seventy miles to the south, the Union IV and XXIII Corps under General Schofield, twenty-six thousand strong, awaited Hood’s advance at Pulaski, Tennessee. Thomas’ cavalry commander, Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, had about four thousand troopers with Schofield, but his command was in desperate need of horses and equipment. Another ten thousand soldiers of the XVI Corps under General A. J. Smith were en route from Missouri. To buy time for their arrival, Thomas instructed Schofield to delay the Army of Tennessee’s advance, and he ordered Wilson to keep Forrest away from the railroads. He also called in his garrisons and outposts to prevent them from being gobbled up by the Confederates.

As Hood’s army approached from the southwest, Schofield withdrew from Pulaski on 24 November and marched toward Columbia thirty miles to the north. Forrest, meanwhile, sent his six thousand cavalry on a wide sweep to cut off Schofield’s retreat. But the Federal infantry had arrived well ahead of the Confederate cavalry and were already dug in along the Duck River.

Borrowing a page from Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign tactics, Hood launched a flanking maneuver around the Union left with the bulk of his army, while two infantry divisions kept the Federals occupied at Columbia. On the morning of 29 November, Forrest briefly clashed with Wilson’s Union cavalry, drawing it away from Schofield’s column, and then made a dash for the village of Spring Hill, Tennessee, about ten miles to the north. In the meantime, Schofield ordered his wagon train to withdraw toward Spring Hill on the Columbia Pike. The IV Corps under Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley was escorting the Federals’ eight hundred wagons and forty pieces of artillery when Stanley learned that the Union garrison at Spring Hill was under attack. He passed the word to the commander of his lead brigade, Col. Emerson Opdycke, who gave the order to advance up the turnpike at a run. The race to Spring Hill was on. When Forrest’s troopers reached Spring Hill, two IV Corps brigades were waiting for them, and a third was on the way. The Confederate cavalry, fighting dismounted, lacked the numbers to drive the Federal infantry. They could only watch as the Union wagon train rumbled through Spring Hill and went into park just north of town. At 1500, as the Confederate infantry approached to within a few miles of Spring Hill, Hood directed that Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham deploy his corps east of Spring Hill on Forrest’s left. Cheatham was to advance west toward the Columbia Pike and the Union column, and then wheel north, driving the enemy through Spring Hill, while Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart’s corps waited in reserve to support Cheatham’s attack if needed.

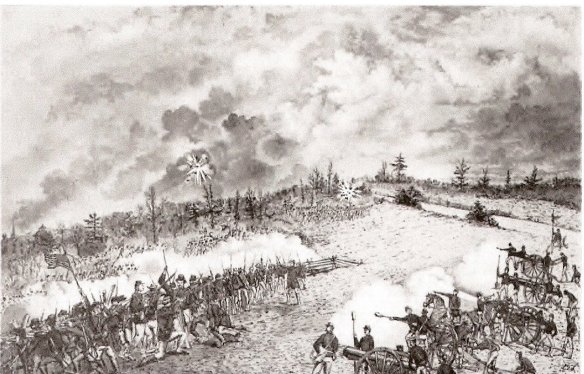

By the time Cheatham’s lead division under Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne arrived at Spring Hill one hour later, Hood had modified his orders. He directed Cleburne to head west toward the Columbia Pike and then swing south to drive the Union column back toward Columbia. Hood’s intent was to prevent Schofield’s XXIII Corps at Columbia from reaching Stanley’s IV Corps at Spring Hill. Hood issued the same order to Maj. Gen. William B. Bate, whose division formed on Cleburne’s left. Cheatham was unaware of the change in orders, however, and just before Cleburne launched his assault, he reiterated his order to “take” Spring Hill. He also directed Bate to conform to Cleburne’s movements, in effect countermanding Hood’s order. The conflicting orders created much confusion among the two division commanders and their staff officers, but after some discus- sion, they decided to heed Cheatham’s order to attack toward Spring Hill. Overrunning a Union infantry brigade, Cleburne’s three brigades came face-to-face with eighteen Federal cannons that General Stanley had deployed south of town. The guns blazed forth in the fading light, sending the Confederates scurrying for cover. Nightfall brought an end to Cleburne’s assault. The action had cost the Federals about 400 casualties and the Confederates roughly 250 losses.

Instead of deploying across the Columbia Pike to block Schofield’s approach route to Spring Hill, the Confederates went into camp along the roadside, confident that they had trapped the Federals south of town and could dispose of them in the morning. Complacency and miscommunication among the Confederate high command enabled Schofield’s column to march past in the darkness without being challenged. Historian Wiley Sword describes the Union escape at Spring Hill “as one of the greatest missed opportunities of the entire war.”

Hood awoke to learn that the Federals had slipped past his army during the night. He was furious. That morning he summoned his senior subordinates to a conference and lashed out at them for allowing the enemy to escape. Forrest’s cavalry, meanwhile, pursued the Union rear guard—namely Opdycke’s brigade—toward the village of Franklin, Tennessee, about a dozen miles north of Spring Hill. The Army of Tennessee’s infantry followed a few miles behind the cavalry.