At the conclusion of the fifteenth century, Italy remained divided. There were four kingdoms: Sardinia, Sicily, Corsica, and Naples; many republics such as Venice, Genoa, Florence, Lucca, Siena, San Marino, Ragusa (in Dalmatia); small principalities, Piombino, Monaco; and the duchies of Savoy, Modena, Mantua, Milan, Ferrara, Massa, Carrara, and Urbino. Parts of Italy were under foreign rule. The Habsburgs controlled the Trentino, Upper Adige, Gorizia, and Trieste. Sardinia belonged to the kingdom of Aragon. Many Italian states, however, held territories outside of the peninsula. The duke of Savoy possessed the Italian region of Piedmont and the French-speaking Duchy of Savoy along with the counties of Geneva and Nice. Venice owned Crete, Cyprus, Dalmatia, and many Greek islands. The Banco di San Giorgio, the privately owned bank of the republic of Genoa, possessed the kingdom of Corsica. Italian princes also held titles and fiefdoms in neighboring states. Indeed, the duke of Savoy could also claim that he was heir and a descendant of the crusader kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem. All of this confusion often remained a source of contention in Italian politics.

The Muslims became the greatest threat to security when the Arabs occupied Sicily in the ninth century. Later Muslim attempts to conquer central Italy failed as a result of papal resistance. Although the Norman conquest of southern Italy and Sicily removed the immediate threat. Muslim ships raided the Italian coast until the 1820s.

This conflict with Islam resulted in substantial Italian participation in the Cru- sades. The Crusader military orders such as the Templars and the Order of Saint John were populated by a great number of Italian knights. Italian merchants, too, established their own warehouses and agencies in the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. Thanks to the Crusades, Venice and Genoa increased their influence as well. They expanded their colonies, their revenues, and their importance to the Crusader kingdoms. Their wealth exceeded that of many European kingdoms.

The fall of the Crusader kingdoms, the Turkish conquests, and the fall of Constantinople by 1453 led to two significant consequences: the increasing influence of Byzantine and Greek culture in Italian society, and the growing Turkish threat to Italian territorial possessions in the Mediterranean. The conflict between Italians and Muslims was complex. For centuries Italians and Muslims were trading partners. So the wars between the Turks and Venetians therefore consisted of a combination of bloody campaigns, privateering, commerce, and maritime war lasting more than 350 years.

Despite a common enemy, common commercial and financial interests, a common language, and a common culture, Italian politics remained disparate and divisive. For much of the fifteenth century the states spent their time fighting each other over disputed territorial rights. Although they referred to themselves as Florentines, Lombards, Venetians, Genoese, or Neapolitans, when relating themselves to outsiders, such as Muslims, French, Germans, and other Europeans, they self- identified as “Italians.”

The Organization of Renaissance Armies

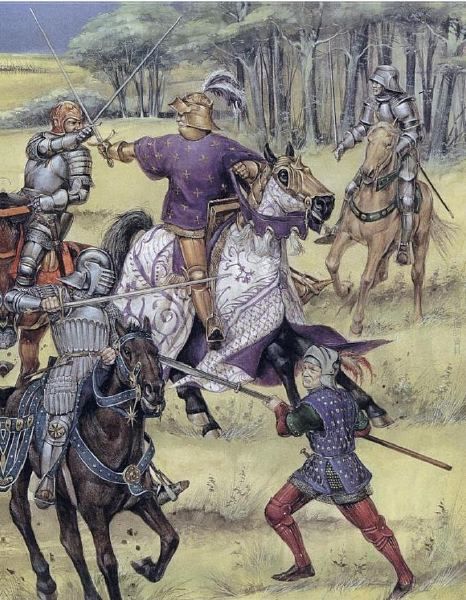

The lack of significant external threats led to the reduction in size of Italian armies. The cost of maintaining standing armies or employing their citizenry in permanent militias was too expensive and reduced the productivity of the population. Italian city-states, duchies, and principalities preferred to employ professional armies when needed, as they were extremely costly to hire. Larger states, such as the Republic of Venice, the Kingdom of Naples and the Papal States possessed a limited permanent force, but the remainder of the Italian states had little more than city guards, or small garrisons. Nevertheless, Italian Renaissance armies, when organized, were divided into infantry and cavalry. Artillery was in its infancy and remained a severely limited in application. Cavalry was composed of heavy or armored cavalry, genti d’arme (men at arms), and light cavalry. Since the Middle Ages, genti d’arme were divided into “lances” composed of a “lance chief”—or corporal—a rider, and a boy. They were mounted on a warhorse, a charger, and a jade respectively. The single knight with his squire was known as lancia spezzata— literally “brokenspear,” or anspessade.

Infantry was divided into banners. Every banner was composed of a captain, two corporals, two boys, ten crossbowmen, nine palvesai, soldiers carrying the great medieval Italian shields called palvesi, and a servant for the captain. Generally the ratio of cavalry to infantry was one to ten. There was no organized artillery by the end of the fifteenth century, as it was relatively new to European armies.

An Evolution in Military Affairs, or the So-Called “Military Revolution”

Artillery was in its infancy during the fifteenth century, but in the early days of the sixteenth century, a quick and impressive development began. The Battle of Ravenna in 1512 marked the first decisive employment of cannons as field artillery. Soon infantry and cavalry realized the power of artillery and proceeded to alter their tactics to avoid or at least to reduce the damage. Moreover, the increasing power of artillery demonstrated the weakness of medieval castles and led to a trans- formation of military architecture. The traditional castle wall was vertical and tall and could be smashed by cannon-fired balls. In response, the new Italian-styled fortress appeared. Its walls were lower and oblique instead of perpendicular to the ground. The walls resisted cannonballs better, as their energy could also be diverted by the obliquity of the wall itself. Then, the pentagonal design was determined as best for a fortress, and each angle of the pentagon was reinforced by another smaller pentagon, called a bastion. It appeared as the main defensive work and was protected by many external defensive works, intended to break and scatter the enemy’s attack. The fifteenth-century Florentine walls in Volterra have many bastion elements, but the first Italian-styled fortress was at Civitavecchia, the harbor for the papal fleet, forty miles north of Rome. It was erected by Giuliano da Sangallo in 1519, but recent studies suggest that Sangallo exploited an older draft by Michelangelo.

The classical scheme of the Italian-styled fortress often referred to as the trace italienne was established in the second half of the sixteenth century. Its elegant efficiency was recognized by all powers. European sovereigns called upon Italian military architects to build these new fortresses in their countries. Antwerp, Parma, Vienna, Györ, Karlovac, Ersekujvar, Breda, Ostend, S’Hertogenbosch, Lyon, Char- leville, La Valletta, and Amiens all exhibited the style and ability of Giuliano da Sangallo, Francesco Paciotti, Pompeo Targone, Gerolamo Martini, and many other military architects, who disseminated a style and a culture to the entire Continent. The pentagonal style was further developed by Vauban and soon reached America, too, where many fortresses and military buildings were built on a pentagonal scheme.

This evolution in military architecture—generally known as “the Military Revolution”—meant order and uniformity. A revolution also occurred in uniforms and weapons. Venetian infantrymen shipping on galleys for the 1571 naval campaign were all dressed in the same way; and papal troops shown in two 1583 frescoes are dressed in yellow and red, or in white and red, depending on the company to which they belonged. Likewise, papal admiral Marcantonio Colonna, in 1571, ordered his captains to provide all their soldiers with “merion in the modern style, great velveted flasks for the powder, as fine as possible, and all with well ammunitioned match arquebuses . . . ” Of course, uniformity remained a dream, especially when compared with eighteenth- or nineteenth-century styles, but it was a first step.

Although a revolution in artillery and fortifications remained a significant aspect of the military revolution, captains faced the problem of increasing firepower. The Swiss went to battle in squared formations, but it proved to be unsatisfactory against artillery. Similarly, portable weapons could not fire and be reloaded fast enough, and it soon became apparent that armies needed a mixture of pike and firearms. The increasing range and effectiveness of firearms made speed on the field more important. It was clear that the more a captain could have a fast fire–armed maneuvering mass, the better the result in battle. Machiavelli examined this issue; he was as bad a military theorist as he was a formidable political theorist. He suggested the use of two men on horseback: a rider and a scoppiettiere—a “hand- gunner”—on the same horse. It was the first kind of mounted infantry in the modern era. Giovanni de’Medici, the brave Florentine captain known as Giovanni of the Black Band, adopted this system. Another contemporary Florentine captain, Pietro Strozzi, who reduced the men on horseback to only one, developed the same system. He fought against Florence and Spain, then he passed to the French flag at the end of the Italian Wars. When in France, he organized a unit based upon his previous experience. It was composed of firearmed riders, considered mounted infantrymen, referred to as dragoons.