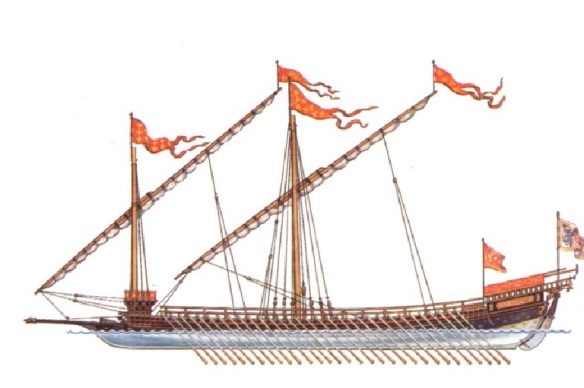

GALIOT (GALLIOT) Mediterranean

In the 16th century, a galiot was a type of ship with oars, also known as a half-galley. The Galiot was long, and sleek with a flush deck. Then, from the 17th century forward, a ship with sails and oars. As used by the Barbary pirates against the Republic of Venice, a galiot had two masts and about 16 ranks of oars. Warships of the type typically carried between two and ten cannons of small caliber, and between 50 and 150 men. She was used by the Barbary corsairs in the Mediterranean.

The greatest threat to Italy was piracy. Mediterranean pirates and privateers were both Christian and Muslim, and there was little difference between them in violence and cruelty; but Italians generally considered the Muslim pirates their major enemy. Barbarian regencies of Tripoli—in Libya—Tunis, and Algiers in North Africa were centers of piracy. In theory, they were dependencies of the Ottoman Empire, but the Sultan’s authority was weak and Istanbul far away. The Uscocks, Croatian pirates, preyed upon Adriatic shipping, as their ports lay on the Dalmatian coast under Habsburg protection. Venetian and Turkish vessels were their primary targets.

There was a difference between pirates and privateers. Privateers were formally permitted by a sovereign to fight against that sovereign’s enemies. They could only attack vessels under an enemy flag. Pirates attacked everything, independently of flag. When captured, privateers were considered as prisoners of war; pirates could be killed or hanged. Death, however, was not enough to stop them. Northern African regencies needed piracy because it was their primary source of revenue. Their domestic economy was largely agricultural and few goods produced were exported.

In fact, pillaging a vessel or a coastal town gave them money and goods to be sold for money, and, above all, slaves. Before steam power, the easiest and cheapest available manpower was the slave. Captured seamen and passengers, or peasants, fishermen, and citizens were carried to northern African and Ottoman ports to be sold. Wealthier captives were often ransomed. Many of the strongest slaves were not sold but used on galleys as oarsmen. Slavery substantially disappeared in Italy in the Middle Ages, but Muslim prisoners were used largely as oarsmen, or galley slaves. As the need for oarsmen became greater, Italian coastal states condemned their criminals to serve on the galleys as oarsmen, hence the word “galley” became synonymous with “prison” as well the term “bath”—the place where the slaves normally stayed—for “penal bath.”

Pirates had vessels set for their tasks. Their targets had to be taken by surprise. A coastal town had to be reached in spite of low waters, and the vessel had to be able to move as quickly as possible to escape as well as to reach an enemy. This meant small and light ships were generally employed for purposes of raiding. Moreover, light ships could move by oars no matter the weather, and the Mediterranean had less wind than the Atlantic. Sometimes the ships had an opposite wind or no wind at all. That’s why the ancient galleys, for two thousand years, were propelled by sails and oars. A galley could be as fast as a sailing ship—as the Venetians tested—and it moved also without wind. Of course, it needed a lot of men—slaves, voluntary oarsmen, seamen, marine infantrymen, gunners—and this meant a high consumption of food and water, so that the ship had only a four-to-seven-day sea range. The Mediterranean, however, is relatively compact; its shores can be quickly reached to find water and fresh foods, thus galleys were the best choice. And galleys were integral parts of Italian navies until the French Revolution and Napoleonic era. They disappeared only after 1814, when the Royal Sardinian Navy abandoned them. As piracy was a persistent menace and the galley the only good weapon to fight it, all the Italian navies were primarily composed of galleys. Of course, many possessed sailing ships, too, but they were not as relevant as galleys in quantity and importance. Naval officers serving on galleys held a higher rank than those serving on vessels.

Since the seventeenth century, Italian fleets were divided into Squadra delle Galere—literally being the Italian the word squadrone used only for cavalry, the “squad of galleys”—and the Squadra dei Vascelli—the “squad of vessels”—or, as the Venetians referred to them: the Light Squadron and the Heavy, or the Big, Squadron, also called “the Big Army,” and the “the Light Army.” The Heavy Squadron included all the square-sailed vessels; the Light one included rowing ships—galleys, galleasses, half galleys, and galliots—as well as the lateen-sailed vessels like schooners, tartans, and ketches. In all the Italian states, except Venice, the Light Squadron comprised the entire fleet and usually had no more than six galleys.

If we consider Italy’s long coasts, it was impossible to patrol blue waters to protect merchant traffic and the coast with so few ships. The Adriatic was generally safe. The Republic of Venice protected the northern Adriatic, her fleet was strong and, moreover, the Most Serene Republic had an agreement with Istanbul: No man-of-war under sultan’s formal authority—which included Barbary pirates—was allowed to sail in the Adriatic. This agreement remained in effect until the fall of the republic in 1797. Venice maintained permanent naval squadrons protecting her commercial routes. The “Guardia in Candia,” based in the capital of Crete, controlled eastern Mediterranean waters. The “Guardia in Golfo”—guard in the Gulf—at Corfù, protected the entrance to the Adriatic Sea, at that time proudly called “the Gulf of Venice.”

Beyond the protection of Venice, the southern—Ionian and western Tyrrhenian—seas were open to piracy. Maltese, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Tuscan, Genoese, and papal fleets hardly totaled more than forty-five galleys. They had no centralized command, no coordination, and they had to protect 2,600 miles of coastline. This meant that in the best possible situation, using all the galleys at the same time, there could be no more than one galley every fifty-seven miles. In fact, when considering that normally a six-galley fleet had two galleys on patrol, two galleys just back or coming back to the port, and two galleys preparing to go out, every galley had to patrol 173 miles coastline, and none in blue waters. It was clearly impossible to stop pirates. The only way to reduce the threat consisted of land-based standing forces. That’s why the Italian coast, from Nice in the northern Tyrrhenian Sea to the Gargano promontory in the southern Adriatic Sea—just out of Venetian waters—was filled with watchtowers. Every tower had cannons to fire against pirates and wood for a signal fire, to warn the towns and the villages of the approaching menace and to call infantry and cavalry from the castles in the interior. All of this, however, remained insufficient to stem the threat, and Italian coastal populations concentrated in the well-fortified port cities or escaped to the interior. Towns were built on the top of hills or mountains. Coastal routes were abandoned as well as the country near the sea. Marshes became larger and larger, especially from south of Pisa down to north of Naples, because no one drained the country as the Etruscans and Romans had. Mosquitoes increased and carried malaria—literally “naughty air” or “evil air”—and this disease, which was supposed to come from the country air, forced the people to concentrate in the cities, were malaria was not so terrible or did not exist at all.

The Ottoman Threat

In the latter half of the sixteenth century, the Sublime Porte continued to export its power into the Balkans and Mediterranean. Strategically, the Mediterranean world was divided into two spheres of influence, with Italy as its geographic bound- ary. The Muslim sphere under Turkish rule, included the eastern Mediterranean, North Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans. The Christian sphere under essentially Spanish control included the western Mediterranean from Gibraltar to Italy. The sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, pursued a horizontal expansion, from east to west with Italy at the epicenter. Muslim efforts to conquer Italy had failed in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Neapolitan troops repeatedly repelled Turkish landing forces in Apulia, at the heel of the Italian boot. The last time, in 1537, an enormous Turkish fleet approached Apulia along the Adriatic coast, confident of Venetian neutrality. The entire operation failed because of the sudden appearance of a Venetian squadron. Venice later explained to the Porte that the squadron commander had misunderstood his orders, but Istanbul suspected Venetian duplicity and decided not to attempt a second invasion.

Suleiman considered an alternative strategy, not wanting to add Venice to his list of enemies. If he could not conquer Italy, or at the very least Naples, Suleiman decided to bypass the peninsula, sending his fleet into the western Mediterranean through the Channel of Sicily, between Tunisia and Sicily. This operation, how- ever, would only succeed if the Turks could seize the strategically critical island of Malta. The Knights Hospitalars of Saint John, better known as the Knights of Malta, defended the island. Malta possessed a valuable harbor and would be a critical base for the conquest of the western Mediterranean.

In the spring of 1565, 188 Turkish vessels sailed to Malta along with 48 additional war galleys from Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers. They escorted an enormous invasion fleet, which carried 38,000 soldiers, 25,000 pioneers, and powerful siege artillery. News of the Turkish assault spread rapidly throughout Europe. Venice reinforced its Mediterranean garrisons, and the duke of Tuscany, the Republic of Genoa, and the papacy sent reinforcements to the island. The duke of Savoy provided supplies and dispatched his galleys. King Philip II of Spain ordered the Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, and Spanish galley squadrons to assemble at the Sicilian city of Messina to aid Malta. The king of France, Francis II, did nothing, as he maintained a secret agreement with the Turks.

On May 20, 1565, the Turkish fleet under Piali` Pasha reached Malta. Grand Master Jean de La Valette had only 541 knights—169 of them Italians—6,000 Maltese, and 2,600 Spanish soldiers garrisoning the three forts, Saint Elmo, San Michele, and Saint Angelo. The Turks failed to take Sant’Elmo by storm for a price of 3,000 dead compared to only 120 knights. In the following days the Turks isolated and repeatedly attacked the fort, finally prevailing on June 17. No quarter was given, and the few prisoners were flayed alive. They were then fixed on planks, and the planks were launched into the sea under the horrified eyes of the knights in the two other forts. The Turks subsequently attacked San Michele. Their first assault cost 2,000 dead and failed. Piali` Pasha then employed alternate bombardment and infantry attacks. The fort held and, on September 7, a Christian fleet reached Malta. Composed of sixty galleys from Tuscany, Naples, Sicily, Savoy, Genoa, Sardinia, and Rome, they landed an expeditionary force of infantry and cavalry. Divided into three columns, 8,000 Italian and Spanish soldiers attacked the Turks. Their attempt to deploy their army for battle failed due to a charge by Tuscan cavalry, which threw the Turks into disarray, cutting them in pieces. Piali` Pasha’s army was destroyed, only 3,000 remained on the field. The routed army fled to the ships and abandoned the invasion. After a 110-day siege, Turkish casual- ties amounted to 20,000 men. The Christians lost 214 knights and some 5,000 soldiers. Malta was saved, and Suleiman’s plans for the invasion of the western Mediterranean failed.