French Army

Turkish Troops

British Army

By this time the British and the French were assembling their armies in the Varna area. They had begun to land their forces at Gallipoli at the beginning of April, their intention being to protect Constantinople from possible attack by the Russians. But it soon became apparent that the area was unable to support such a large army, so after a few weeks of foraging for scarce supplies, the allied troops moved on to set up other camps in the vicinity of the Turkish capital, before relocating well to the north at the port of Varna, where they could be supplied by the French and British fleets.

The two armies set up adjacent camps on the plains above the old fortified port – and eyed each other warily. They were uneasy allies. There was so much in their recent history to make them suspicious. Famously, Lord Raglan, the near-geriatric commander-in-chief of the British army, who had served as the Duke of Wellington’s military secretary during the Peninsular War of 1808–14 and had lost an arm at Waterloo,s would on occasion refer to the French rather than the Russians as the enemy.

From the start there had been disputes over strategy – the British favouring the landing at Gallipoli followed by a cautious advance into the interior, whereas the French had wanted a landing at Varna to forestall the Russian advance towards Constantinople. The French had also sensibly suggested that the British should control the sea campaign, where they were superior, while they should take command of the land campaign, where they could apply the lessons of their war of conquest in Algeria. But the British had shuddered at the thought of taking orders from the French. They mistrusted Marshal Saint-Arnaud, the Bonapartist commander of the French forces, whose notorious speculations on the Bourse had led many in Britain’s ruling circles to suppose that he would put his own selfish interests before the allied cause (Prince Albert thought that he was even capable of accepting bribes from the Russians). Such ideas filtered down to the officers and men. ‘I hate the French,’ wrote Captain Nigel Kingscote, who like most of Raglan’s aides-de-camp was also one of his nephews. ‘All Saint-Arnaud’s staff, with one or two exceptions, are just like monkeys, girthed up as tight as they can be and sticking out above and below like balloons.’

The French took a dim view of their British allies. ‘Visiting the English camp makes me proud to be a Frenchman,’ wrote Captain Jean-Jules Herbé to his parents from Varna.

The British soldiers are enthusiastic, strong and well-built men. I admire their elegant uniforms, which are all new, their fine comportment, the precision and regularity of their manoeuvres, and the beauty of their horses, but their great weakness is that they are used to comfort far too much; it will be difficult to satisfy their numerous demands when we get on the march.

Louis Noir, a soldier in the first battalion of Zouaves, the élite infantry established during the Algerian War, recalled his miserable impression of the British troops at Varna. He was particularly shocked by the floggings that were often given by their officers for indiscipline and drunkenness – both common problems among the British troops – which reminded him of the old feudal system that had disappeared in France:

The English recruiters seemed to have brought out the dregs of their society, the lower classes being more susceptible to their offers of money. If the sons of the better-off had been conscripted, the beatings given to the English soldiers by their officers would have been outlawed by the military penal code. The sight of these corporal punishments disgusted us, reminding us that the Revolution of [17]89 abolished flogging in the army when it established universal conscription … . The French army is made up of a special class of citizens subject to the military laws, which are severe but applied equally to all the ranks. In England, the soldier is really just a serf – he is no more than the property of the government. It drives him on by two contradictory impulses. The first is the stick. The second is material well-being. The English have a developed instinct for comfort; to live well in a comfortable tent with a nice big side of roast-beef, a flagon of red wine and a plentiful supply of rum – that is the desideratum of the English trooper; that is the essential precondition of his bravery … . But if these supplies do not arrive on time, if he has to sleep out in the mud, find his firewood, and go without his beef and grog, the English become battle-shy, and demoralization spreads through the ranks.

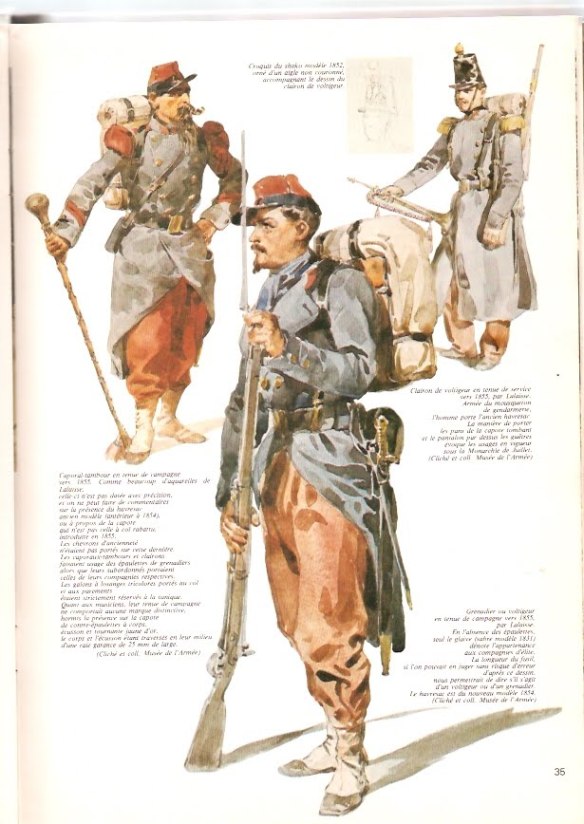

The French army was superior to the British in many ways. Its schools for officers had produced a whole new class of military professionals, who were technically more advanced, tactically superior and socially far closer to their men than the aristocratic officers of the British army. Armed with the advanced Minié rifle, which could fire rapidly with lethal accuracy up to 1,600 metres, the French infantry was celebrated for its attacking élan. The Zouaves, in particular, were masters of the fast attack and tactical retreat, a type of fighting they had developed in Algeria, and their courage was an inspiration to the rest of the French infantry, who invariably followed them into battle. The Zouaves were seasoned campaigners, experienced in fighting in the most difficult and mountainous terrain, and united by strong bonds of comradeship, formed through years of fighting together in Algeria (and in many cases on the revolutionary barricades of Paris in 1848). Paul de Molènes, an officer in one of the Spahi cavalry regiments recruited by Saint-Arnaud in Algeria, thought the Zouaves exerted a ‘special power of seduction’ over the young men of Paris, who flocked to join their ranks in 1854. ‘The Zouaves’ poetic uniforms, their free and daring appearance, their legendary fame – all this gave them an image of popular chivalry unseen since the days of Napoleon.’

The experience of fighting in Algeria was a decisive advantage for the French over the British army, which had not fought in a major battle since Waterloo, and in many ways remained half a century behind the times. At one point a third of the French army’s 350,000 men had been deployed in Algeria. From that experience, the French had learned the crucial importance of the small collective unit for maintaining discipline and order on the battlefield – a commonplace of twentieth-century military theorists that was first advanced by Ardant du Picq, a graduate of the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr, the élite army school at Fontainebleau near Paris, who served as a captain in the Varna expedition and developed his ideas from observations of the French soldiers during the Crimean War. The French had also learned how to supply an army on the march efficiently – an area of expertise where their superiority over the British became apparent from the moment the two armies landed at Gallipoli. For two and a half days, the British troops were not allowed to disembark, ‘because nothing was ready for them’, reported William Russell of The Times, the pioneering correspondent who had joined the expedition to the East, whereas the French were admirably prepared with a huge flotilla of supply ships: ‘Hospitals for the sick, bread and biscuit bakeries, wagon trains for carrying stores and baggage – every necessary and every comfort, indeed, at hand, the moment their ship came in. On our side not a British pendant was afloat in the harbour! Our great naval state was represented by a single steamer belonging to a private company.’

The outbreak of the Crimean War had caught the British army by surprise. The military budget had been in decline for many years, and it was only in the early weeks of 1852, following Napoleon’s coup d’état and the eruption of the French war scare in Britain, that the Russell government was able to obtain parliamentary approval for a modest increase in expenditure. Of the 153,000 enlisted men, two-thirds were serving overseas in various distant quarters of the Empire in the spring of 1854, so troops for the Black Sea expedition had to be recruited in a rush. Without the conscription system of the French, the British army relied entirely on the recruitment of volunteers with the inducement of a bounty. During the 1840s the pool of able-bodied men had been severely drained by great industrial building projects and by emigration to the United States and Canada, leaving the army to draw upon the unemployed and poorest sections of society, like the victims of the Irish famine, who took the bounty in a desperate attempt to clear their debts and save their families from the poorhouse. The main recruiting grounds for the British army were pubs and fairs and races, where the poor got drunk and fell into debt.

If the British trooper came from the poorest classes of society, the officer corps was drawn mostly from the aristocracy – a condition almost guaranteed by the purchasing of commissions. The senior command was dominated by old gentlemen with good connections to the court but little military experience or expertise; it was a world apart from the professionalism of the French army. Lord Raglan was 65; Sir John Burgoyne, the army’s chief engineer, 72. Five of the senior commanders at Raglan’s headquarters were relatives. The youngest, the Duke of Cambridge, was a cousin to the Queen. This was an army, rather like the Russian, whose military thinking and culture remained rooted in the eighteenth century.

Raglan insisted on sending British soldiers into battle in tight-fitting tunics and tall shakos that might have made them look spectacular when marched in strict formation on the parade ground but which in a battle were quite impractical. When Sidney Herbert, the Secretary at War, wrote to him in May suggesting that the dress code ought to be relaxed and that perhaps the men might be excused from shaving every day, Raglan replied:

I view your proposition for the introduction of beards in somewhat a different light, and it cannot be necessary to adopt it at present. I am somewhat old-fashioned in my ideas, and I cling to the desire that an Englishman should look like an Englishman, notwithstanding that the French are endeavouring to make themselves appear as Africans, Turks, and Infidels. I have always remarked in the lower orders in England, that their first notion of cleanliness is shaving, and I dare say this feeling prevails in a great deal in our ranks, though some of our officers may envy the hairy men amongst our Allies. However, if when we come to march and are exposed to great heat and dirt, I remark that the sun makes inroads on the faces of the men, I will consider whether it be desirable to relax or not, but let us appear as Englishmen.

The sanction against beards did not last beyond the July heat, but the British soldier was still ridiculously overdressed compared to the light and simple uniforms of the Russians and the French, as Lieutenant Colonel George Bell of the 1st (Royal) Regiment complained:

A suit on his back & a change in his pack is all the men require but still he is loaded like a donkey – Great coat & blanket, tight … belts that cling to his lungs like death, his arms and accoutrements, 60 rounds of Minié ammunition, pack & contents. The stiff leather choker we have abolished thanks to ‘Punch’ and the ‘Times’. The reasoning of 40 years experience would not move the military authorities to let the soldier go into the field until he was half strangled & unable to move under his load until public opinion and the Newspapers came in to relieve him. The next thing I want to pitch aside is the abominable Albert,u as it is called, whereon a man may fry his ration beef at mid-day in this climate, the top being patent leather to attract a 10 fold more portion of the sun’s rays to madden his brain.

Encamped on the plains around Varna, with nothing much to do but wait for news from the fighting at Silistria, the British and French troops sought out entertainments in the drinking-places and brothels of the town. The hot weather and warnings not to drink the local water resulted in a monstrous drinking binge, especially of the local raki, which was very cheap and strong. ‘Thousands of Englishmen and Frenchmen thronged together in the improvised taverns,’ wrote Paul de Molènes, ‘where all the wines and liquors of our countries poured out into noisy drunkenness … The Turks stood outside their doors and watched without emotion or surprise these strange defenders that Providence had sent to them.’ Drunken fighting between the men was a daily problem in the town. Hugh Fitzhardinge Drummond, an adjutant of the Scots Fusilier Guards, wrote to his father from Varna:

Our friends, the Highlanders, drink like fishes, and our men … drink more than they did at Scutari. The Zouaves are the most ill-behaved and lawless miscreants you can imagine; they commit every crime. They executed another man the day before yesterday. Last week a Chasseur de Vincennes was nearly cut in half by one of these ruffians, with a short sword, in a fit of mad drunkenness. The French drink a great deal – I think as much as our men – and when drunk are more insubordinate.

Complaints from the residents of Varna multiplied. The town was populated mainly by Bulgarians, but there was a sizeable Turkish minority. They were irritated by soldiers demanding alcohol from Muslim-owned cafés and becoming violent when they were told that it was not sold. They might have been excused for wondering whether their defenders were a greater danger to them than the menace of Russia, as British naval officer Adolphus Slade observed from his vantage point in Constantinople:

French soldiers lounged in the mosques during prayers, ogled licentiously the veiled ladies, poisoned the street dogs … shot the gulls in the harbour and the pigeons in the streets, mocked the muezzins chanting ezzan from the minarets, and jocosely broke up carved tombstones for pavement … The Turks had heard of civilization: they now saw it, as they thought, with amazement. Robbery, drunkenness, gambling, and prostitution revelled under the glare of an eastern sun.

The British quickly formed an ill opinion of the Turkish soldiers, who set up camp beside them on the plains around Varna. ‘The little I have seen of the Turks makes me think they are very poor allies,’ Raglan’s aide-de-camp Kingscote wrote to his father. ‘I am certain they are the greatest liars on the face of the earth. If they say they have 150,000 men you will find that on enquiry there are only 30,000. Everything in the same proportion, and from all I hear, I cannot make out why the Russians have not walked over them.’ The French also did not think much of the Turkish troops, although the Zouaves, who contained a large contingent of Algerians, established good relations with the Turks. Louis Noir thought the British soldiers had a racist and imperial attitude towards the Turks that made them widely hated by the Sultan’s troops.

The English soldiers believed they had come to Turkey, not to save it, but to conquer it. At Gallipoli they would often have their fun by accosting a Turkish gentleman along the beach; they would draw a circle around him and tell him that this circle was Turkey; then they would make him leave the circle and cut it into two, naming one half ‘England’ and the other ‘France’, before pushing the Turk away into something which they called ‘Asia’.

Colonial prejudice limited the use the Western powers were prepared to make of the Turkish troops. Napoleon III thought the Turks were lazy and corrupt while Lord Cowley, the British ambassador in Paris, advised Raglan that ‘no Turk was to be trusted’ with any military responsibility essential to national security. The Anglo-French commanders thought the Turks were only good at fighting behind fortifications. They were ready to use them for auxiliary tasks such as digging trenches, but assumed they lacked the discipline or courage to fight alongside European troops on the open battlefield. The success of the Turks in holding off the Russians at Silistria (which was largely put down to the British officers) did not change these racist attitudes, which would become even more pronounced when the campaign shifted to the Crimea.

As it was, the Turks were doing more than hold their own against the Russians, who launched one last assault against Silistria on 22 June. On the morning of the 21st, Gorchakov went with his staff to inspect the trenches before the Arab Tabia, where the attack would begin. Tolstoy was impressed by Gorchakov (he would later draw on him for his portrait of General Kutuzov in War and Peace). ‘I saw him under fire for the first time that morning,’ he wrote to his brother Nikolai. ‘You can see he’s so engrossed in the general course of events that he simply doesn’t notice the bullets and cannon-balls.’ Throughout that day, to weaken the resistance of the Turks, 500 Russian guns bombarded their fortifications; the firing continued late into the night. The assault was set for three in the morning. ‘There we all were,’ Tolstoy wrote, and, ‘as always on the eve of a battle, we were all pretending not to think of the following day as anything more than an ordinary day, while all of us, I’m quite sure, at the bottom of our hearts felt a slight pang (and not even slight, but pronounced) at the thought of the assault’.

As you know, Nikolai, the period that precedes an engagement is the most unpleasant – it’s the only period when you have the time to be afraid, and fear is one of the most unpleasant feelings. Towards morning, the nearer the moment came, the more this feeling diminished, and towards 3 o’clock, when we were all waiting to see the shower of rockets let off as the signal for the attack, I was in such a good humour that I would have been very upset if someone had come to tell me that the assault wouldn’t take place.

What he feared most happened. At two o’clock in the morning, an aide-de-camp brought Gorchakov a message, ordering him to raise the siege. ‘I can say without fear of error’, Tolstoy told his brother,

that this news was received by all – soldiers, officers and generals – as a real misfortune, all the more so since we knew through spies who came to us very often from Silistria, and with whom I very often had occasion to talk myself, that once this fort was taken – something of which nobody had any doubt – Silistria couldn’t hold out for more than two or three days.

What Tolstoy did not know, or refused to take into account, was that by this stage there were 30,000 French, 20,000 British and 20,000 Turkish troops ready to reinforce the defence of Silistria, and that Austria, which had massed 100,000 troops along the Serbian frontier, had served an ultimatum to the Tsar to withdraw from the Danubian principalities. Austria had effectively adopted a policy of armed neutrality in favour of the allies, mobilizing Habsburg troops to force the Russians to withdraw from the Danube. Fearful of uprisings among their own Slavs, the Austrians were worried by the Russian presence in the principalities, which looked more like annexation every day. If the Austrians attacked the Russians from the west, there was a real possibility that they would cut them off from their lines of supply on the Danube and block their main path of retreat, leaving them exposed to the allied armies attacking from the south. The Tsar had no choice but to retreat before his army was destroyed.

Nicholas felt a deep sense of betrayal by the Austrians, whose empire he had saved from the Hungarians in 1849. He had developed a paternal affection for the Emperor Franz Joseph, more than thirty years his junior, and felt that he deserved his gratitude. Visibly saddened and shaken by the news of the ultimatum, he turned Franz Joseph’s portrait to the wall and wrote on the back of it in his own hand: ‘Du Undankbarer!’ (You ungrateful man!) He told the Austrian envoy Count Esterhazy in July that Franz Joseph had completely forgotten what he had done for him and that ‘because the confidence which had existed until now between the two sovereigns for the happiness of their empires was destroyed, the same intimate relations could not exist between them any more’.

The Tsar wrote to Gorchakov to explain his reasons for calling off the siege. It was an unusually personal letter that revealed a lot about his thinking:

How sad and painful it is for me, my dear Gorchakov, to be forced into agreement with the persistent arguments of Prince Ivan Fedorovich [Paskevich] … and to retreat from the Danube after having made so many efforts and having lost so many brave souls without gain – I do not need to tell you what that means to me. Judge that for yourself!!! But how can I disagree with him when I look at the map. Now the danger is not so much, for you are in a position to exact a severe punishment on the impudent Austrians. I am fearful only that the retreat may damage the morale of our troops. You must raise their spirits, make it clear to every one of them that it is better to retreat in time so that we can attack later on, as it was in 1812.

The Russians retreated from the Danube, fighting off the Turks, who pursued them, smelling blood. The Russian troops were tired and demoralized, many of the soldiers had not eaten for days, and there were so many sick and wounded that they could not all be taken back by cart. Thousands were abandoned to the Turks. At the fortress town of Giurgevo, on 7 July, the Russians lost 3,000 men in a battle with the Turkish forces (some of them commanded by British officers) who crossed the river from Rusçuk and attacked the Russians with the support of a British gunboat. Gorchakov arrived with reinforcements from the abandoned siege of Silistria, but was soon forced to order a retreat. The Union Jack was planted on the fortress of Giurgevo, where the Turks then took savage revenge on the Russians, killing more than 1,400 wounded men, cutting off their heads and mutilating their bodies, while Omer Pasha and the British officers looked on.