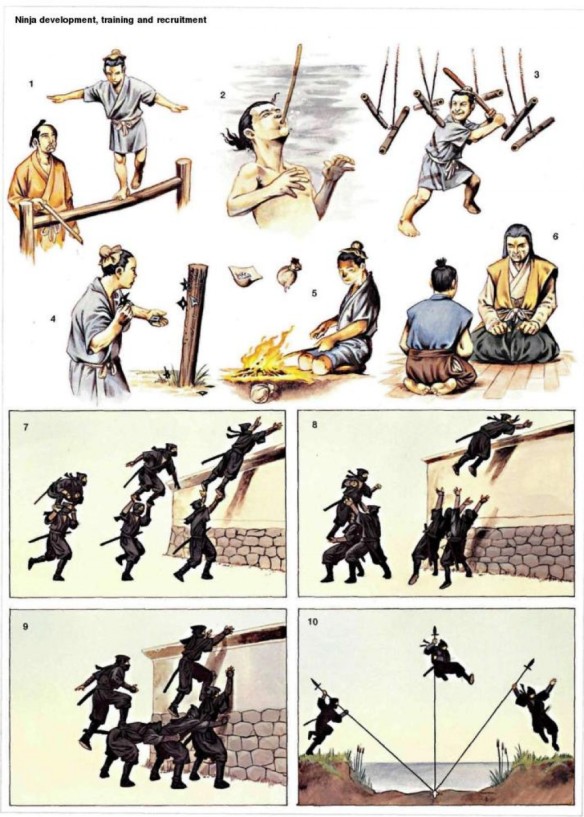

By the beginning of their teenage years, young ninja boys in the ninja villages of Iga and Koga will have internalized the the basics of ninjutsu.

- Ninja kid learning the principles of balance, supervised by his dad, his primary instructor throughout his life.

- Young ninja learning underwater breathing techniques utilizing a bamboo tube. Later in life he might have to hide for hours under the surface of a lake or river to avoid detection by enemies.

- Vital swordsmanship training. Ninja kid taking his first lesson in how to deal with a ring of attackers. He has to anticipate how each bamboo rods will swing back and forth in order to avoid contact with them.

- Ninja boy in extensive missile practice, learning how to spin the shuriken and hit the target accurately.

- Young ninja learning survival skills traveling into the mountains and catering for himself. He is cooking a bag of rice buried under a campfire, with the rice wrapped in a cloth and soaked in water.

- Ninja child interviewed by the shonin, or head of the ninja settlement. He is assessing the child’s progress.

2-, 3- and 4-man techniques for jumping over tall obstacles like walls:

- Ninja teamwork with excellent acrobatic skills. On the other side of the wall the vigilant observer might conclude that the ninja has the ability of flying. In this technique one ninja runs forward carrying his mate on his shoulders, who then leaps from this lifted position.

- Two ninja assisting a third to maneuver over a wall by giving him a powerful ‘leg up’.

- Four men forming a human pyramid.

- Ninja utilizing an ashigaru’s yari, or long spear, to pole-vault over a ditch.

Reconnaissance became a primary concern during the Warring States period (Sengoku jidai, 1467– 1568) and centered on the famed spies known as ninja, whose activities were called ninjutsu (ninja arts and training). The widespread internecine warfare of the mid- to late-Muromachi period made infiltration and information-gathering a focus of military operations. Training in ninja techniques like those described below in “Dagger Throwing” and “Needle Spitting” have relatively recent origins in Japan, despite having developed out of espionage tactics that were fairly common in the medieval era. As with legends praising brave and virtuous samurai, modern (and medieval) misconceptions about ninja traditions have enhanced the ninja mystique. Clothed in notorious secrecy and black garments, and endowed with famed accuracy, acrobatic skills, and awe-inspiring weapons, these figures have played prominent roles in film and literature concerning the martial arts. Most ninja missions supplied little such drama, although concealing the identity of successful ninja was considered paramount.

Famed ninja bands, such as the Iga school (originating in present-day Mie Prefecture) and the Koga school (part of Shiga Prefecture today), were identified with the regions in which they began. Villages in these areas were entirely devoted to instruction and mastery of ninja techniques. Ninja who trained in such regional bands served as scouts, penetrating enemy territory to gather information, conduct assassinations, or simply to distract and confuse the enemy at nighttime. Daimyo relied upon legions of these figures beginning in the 15th century as domains competed for dwindling land and other resources.

Ninja techniques, known as shinobu in Japanese, included strategies of artifice, camouflage, and deception, as well as an array of weapons and tools designed especially for espionage and covert use. In the Warring States period, clandestine missions were critical to military tactics, and thus ninja practices were transmitted orally to maintain secrecy. While medieval samurai enjoyed a somewhat undeserved reputation for noble intentions and valor, ninja temperament was compared to that of a trickster who eschewed the forthright bravery of military retainers, preferring the advantages offered by ambush and sleight of hand. Opportunistic ninja offered themselves as assassins for hire and pirates during the nearly continuous unrest of the 15th to 16th centuries. They became a significant threat in the 16th century. For example, Oda Nobunaga sent 46,000 troops to Iga province in 1581, although tales recount that 4,000 were killed by the Iga ninja.

In the Edo period, threatened with extinction under the enforced Tokugawa peace, ninjutsu became a formal martial art which may have attracted followers simply because of the general fascination with these mysterious, elusive, seemingly magical figures. As ninjutsu became one of the most alluring of the standard 18 military arts (bugeijuhappan), samurai enthusiasts organized ninja teachers, classes, skill requirements, tools, weapons, and techniques systematically in manuals designed for instruction. One of the primary ninja manuals, the Mansen shukai, was compiled in 1676 by Fujibayashi Samuji. This important text detailed the traditions and techniques of the Iga and Koga schools of ninjutsu.