The world’s first successful seaplane flight had taken place on 28 March 1910, when inventor Henri Fabre piloted his floatplane on the Étang de Berre, immediately provoking interest from the French navy. Seven officers were despatched to earn their wings with the Aéro-Club de France and two aircraft were purchased: a Voisin floatplane and a Maurice Farman biplane. Trials based around La Foudre, a converted torpedo-boat tender, were deemed a success, and on 20 March 1912 the Service de l’Aviation Maritime was formed under the command of Capitaine de Frégate Louis Fatou.

Three more bases were planned – at Brest, Cherbourg and Montpellier (soon changed to Saint-Raphaël) – and three aircraft types were recommended for purchase: a coastal seaplane, a land-based reconnaissance aircraft and a light machine for shipboard use. All were initially envisaged in an observation role: ‘While the virtual impregnability and tremendous speed of aeroplanes make them eminently suitable for spotting and reconnaissance, they have little to offer offensively,’ observed the chief of the naval staff on 15 May 1912. The naval manoeuvres of 1914 began to prove, to staff officers at least, that the machines might have some attacking potential, but sea officers remained sceptical. ‘[I was part of] a class of fanatical gunners,’ recalled Aspirant Edmond Benoit, then training at the naval academy. ‘In those days the gun was still the sailor’s weapon of choice.’

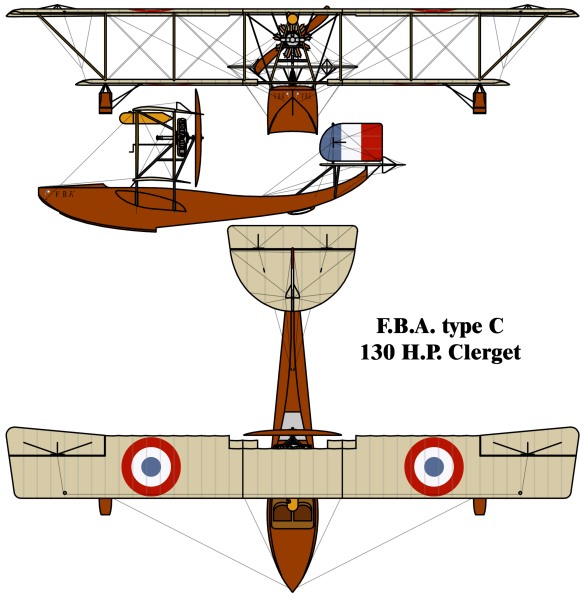

In July 1914 the fledgling service was absorbed into the new Service Central de l’Aéronautique Maritime under the command of Capitaine de Vaisseau Jean Noël. With just twenty-six qualified pilots, La Foudre, the Saint-Raphaël base, and fourteen aircraft – six Nieuport 6H/M, six Voisins, a Caudron and a Breguet – it was a tiny affair, but the outbreak of war provoked its immediate expansion. Ten new seaplanes were purchased, two squadrons formed at Bonifacio and Nice, and two merchantmen requisitioned for conversion as seaplane carriers (plus two more in 1915). In December 1914 bases were established at Dunkerque and Saint-Pol-sur-Mer to control the southern North Sea and conduct anti-submarine warfare, and two months later FBA machines from Dunkerque began raiding the German submarine bases along the coast at Ostend and Zeebrugge.

The Nieuports were sent first to Bizerta (Tunisia), then to Malta and finally to Antivari (Bar) in Montenegro, but their performance did not impress and Vice-Admiral Boué de Lapeyrère, commander of the French Mediterranean fleet, thought them a complete waste of time. They were also dispatched to Port Said where, operating from the seaplane carriers Anne Rickmers and Rabenfels II, they helped repulse a Turkish attack on the Suez Canal in early 1915. Following Italy’s entry into the war that May, a squadron of FBA Type B seaplanes was dispatched to Venice and a flight of Nieuport floatplanes to Brindisi, the latter aiming to bottle up the enemy U-boats in the northern Adriatic by blocking the straits of Otranto. But the Nieuports continued to underperform: ‘These monoplanes have a top speed of 120km/h [and] take 55 minutes to reach their operational height of 2,000 metres,’ reported Capitano di Fregata Ludovico de Filippi, of the Italian seaplane carrier Elba. ‘Patrols normally last three hours … [and] each plane is equipped to carry small bombs…. They are rather fragile, temperamental machines and need perfect weather conditions to take off and land. I therefore consider them unsuitable for long-range missions at sea. And their only [other] weapon is an automatic pistol…. I believe the best use for these planes would be in one-off coastal patrols immediately preceding the arrival or departure of a friendly vessel … or liaising with our destroyers in anti-submarine work.’

By now enemy submarines had become the main focus of the naval aeronautical service. ‘The growth of naval aviation was largely unplanned,’ stated Edmond Benoit. ‘It came in response to the urgent need to protect sea traffic.’ A total of 1,000 flying boats – 500 Donnet-Denhauts and 500 FBA Type Hs – were ordered in 1916, to be distributed between twenty new aviation centres and a further fifteen satellite postes de combat, and by the end of that year 966 planes of all types were operational. Three separate geographical commands were created – [Eastern] English Channel and North Sea, Atlantic and [Western] English Channel, and Mediterranean – each composed of a number of smaller divisions, while a parallel administrative reorganization recognized the growing importance of the service, establishing it as a separate department within the navy ministry and ushering in substantial improvements in operational and logistical efficiency. At the same time research and development became the responsibility of a new technical section, created initially within the naval construction department but transferred in June 1917 to a new directorate of submarine warfare.

The FBA Type H soon proved ineffective in air-to-air combat, as Enseigne de Vaisseau Robert Guyot de Salins and Sergeant Jérôme Médeville discovered during a routine reconnaissance mission along the Belgian coast on 23 October 1916. Their outward journey from Dunkerque was uneventful, but a plane from SFS II climbed to meet them on their return. Two of the three-strong French patrol made off, leaving de Salins and his observer Médeville alone to face the enemy. De Salins dived in a steep spiral. ‘I discharged one magazine, two, then a third,’ recalled Médeville. ‘We closed with him and kept right on his tail. Suddenly some rounds from above alerted us to the presence of a second adversary. I quickly swung the gun in this new direction and, through bracing wires, stays, floats and wings, peppered first one opponent, then the other. Bullets were raining down on all sides. One of my rounds partially severed a bracing wire. My pilot and I checked on each other from time to time…. In mid-action I was hit on the head and slumped down [momentarily] while I gathered my senses. I loaded a fourth magazine while the pilot carried on manoeuvring. The enemy machines made some fantastic turns and all three of us had a number of close calls…. A collision seemed the most likely outcome of this duel…. [But] then the machine gun jammed … and the engine stalled…. Mechanical failure, our worst fear … We landed in enemy waters with the bullets raining down non-stop. We raised our arms in surrender but still they hunted us down … I think [the enemy pilots] had spotted us and were trying to kill us in cold blood.’

Fifteen minutes later the Germans finally broke off, leaving the two Frenchmen to the mercy of a boat coming out of Zeebrugge. Before the pair were captured, they jettisoned everything of use, camera included, and also managed to write a message to their unit, attaching it to the leg of one of their two carrier pigeons – their only means of communication – and releasing the bird. Médeville eventually escaped from captivity in January 1917; Guyot’s fate is unknown.

In an attempt to compensate for the FBA’s poor performance, the French devised new tactics: ‘If you’re attacked in the air, the odds are stacked against you. Touch down at sea straight away and fight from the water.’ But this was equally ineffective. ‘You Frenchmen call it heroic,’ commented a bemused Oberleutnant Friedrich Christiansen, the German CO at Zeebrugge, after three of his Rumplers downed a patrol of four FBA machines from Dunkerque on 26 May 1917. ‘I call it crazy.’

French bombing raids over the Flanders coast – small in number and payload even when reinforced with army Voisins – continued into 1917 against targets in Ostend, Zeebrugge, Gistel and Middelkerke. Their most significant success came in January 1917 with the blocking of the Bruges–Zeebrugge canal, yet they could never deliver a telling blow – unlike the enemy counter-raids. Dunkerque and Calais were targeted throughout the conflict by air, sea and land. A German raid on 23 December 1916 temporarily disabled the Dunkerque base, destroying three hangars and twelve FBA flying boats, while a further action on 2 October 1917 wiped out all the bombers in their hangar. The bomber squadron housed there was disbanded shortly afterwards, although the base continued to operate seaplanes until the end of the war.

Local civilians felt themselves defenceless. ‘The situation is growing worse by the day,’ wrote Félix Coquelle on 23 October. ‘Yesterday evening brought more unwelcome visitors who caused serious damage. We must retaliate, whatever the cost.’ Calais too was suffering: ‘It’s extremely distressing to see … a port so important to the allies – home to representatives from nearly all the belligerent powers and so many people working to defend our nation – so inadequately defended against Boche air raids…. These bandits can operate at night and return calmly the following morning to enjoy their work of destruction and plan their next outing…. Life … is a real nightmare at the moment and I’m not sure if we’ll emerge safe and sound.’ The ordeal would continue deep into 1918: Calais did not hear its final air-raid warning until 25 September; Dunkerque, 4 November. Both towns suffered considerable damage and a significant number of casualties: in Calais, 278 were killed (including 108 civilians) and 528 injured (206 civilians); in Dunkerque, the toll was higher still, with 575 killed (262 civilians) and 1,101 injured (345 civilians).

Dirigibles entered the order of battle in December 1915 for antisubmarine patrols, mine location and convoy escort work, while captive balloons first appeared in April 1917 for use in coastal observation and mine-watching. The first five dirigibles were obtained from Britain – three S.S. and a ‘Coastal’ by purchase, plus a Zodiac by gift – and were soon supplemented by home-produced Vedette and Escorteur types. Then in March 1917 the navy acquired the seven dirigibles released by the army: the Lorraine, Capitaine-Caussin, Tunisie, Champagne and d’Arlandes went to the naval bases in Paimboeuf, Bizerta and Corfu, while the older Fleurus I and Montgolfier became training machines at Saint-Cyr.

Anti-submarine tactics changed during 1917, favouring convoy escort work over attempts to destroy U-boat bases. Balloons and aircraft operated in partnership: a pair of flying boats preceded the convoy by some 25 kilometres, searching for mines or submarines, while a balloon guarded the ships from the rear. ‘The submarines cruised at shallow depths,’ explained Edmond Benoit, who in May 1918 was piloting Donnet-Denhaut flying boats on anti-submarine patrols out of Dunkerque, ‘so the seaplanes could detect them easily enough, even in the foggy, rough waters of the North Sea. When we spotted a submarine, we attacked it with our bombs. It’s very difficult to judge how effective this was. I don’t think I ever managed to sink any. Naval planes in general sank a dozen confirmed. We acted more as a deterrent.’

On 6 September 1917 a British-built VA5 dirigible, based at Montebourg and commanded by Enseigne de Vaisseau Yves Angot, spotted a submarine stalking a schooner: ‘At 10.30 am, exiting cloud, height 300 metres, my wireless and my mechanic both indicated a suspicious object ahead of us and to our right…. Parts of its superstructure were clearly visible, particularly its periscope and another vertical object, no doubt the [wireless] mast.’ Angot dived into the attack but he was uncertain of the outcome. ‘The pilot of this scout thinks it highly unlikely he sank the submarine,’ reported his CO, Lieutenant de Vaisseau Dieudonné, ‘but it performed its mission to perfection and almost certainly prevented the loss of a large coaster. The attack probably failed because [the balloon’s] type-D bombs didn’t work … It is scheduled to carry two British 75-pound bombs, but we only have British 100-pounders at the base and the bomb racks aren’t strong enough to take them. Three men are needed to operate these 2,200m3 balloons, so you can’t carry two 100-pounders even if you reduce all other weight to the absolute minimum. That’s why I decided to try two type-Ds instead. With further modifications, I hope I can make this balloon even more useful.’

The new bases included one in Guernsey, opened in August 1917 – an obvious choice given the island’s location. However, the harbour at St Peter Port was too small for the FBA H flying boats to take off, driving them out to the open sea. ‘With the winds blowing from the South-East to West or North,’ declared a local newspaper, ‘the air is, under the lee of the islands, full of holes and waves just like the sea when it is rough. The machine tries its best to fly but it is buffeted about in all directions, and seems to be always on the verge of a side-slip, which is likely to be fatal when it does occur at a low altitude.’

On 31 January 1918 two Guernsey-based planes – a Tellier and an FBA – were patrolling south of the Les Hanois lighthouse when they spotted what they thought was a submarine. Aware that a French boat was operating in the vicinity, they approached the target carefully, but the submarine had already begun to dive by the time they had definitively identified it. Still they turned their guns on it and watched it struggle back to the surface before heeling over at 45 degrees and disappearing again amid patches of oil. The Guernsey base launched several more attacks on suspicious targets during the final summer of the war, including ‘one greyish object, elongated in form, with spray at the front’, but all were inconclusive.

Over the course of the war the navy trained some 1,500 pilots and observers. Candidates attended the military flying schools for basic pilot training, but in 1917 specialist wings were introduced for seaplane pilots, and schools were opened at Hourtin and Saint-Raphaël to provide additional training for naval pilots and observers. Schools were also established at Brest and later Corfu for captive balloon crews, and at Saint-Cyr (transferred to Rochefort in 1918) for dirigibles. Flying qualifications were open to all: unlike the army, however, officers were few. At the La Penzé base in 1918, for example, only three of the twelve pilots and two of the twenty observers were officers, with the remainder all petty officers or leading seamen. Naval aircrew also tended to be older than their army counterparts: naval promotion was slow even in wartime and any volunteer was required to have some years’ prior sea service. ‘The crews? They were almost all navy men, with relatively few officers and petty officers,’ confirmed Edmond Benoit. ‘They were experienced types who could be relied upon.’

Aspirant Benoit had first volunteered in 1914 while serving on the protected cruiser d’Entrecasteaux, based at Port Said: ‘What made me do it? Novelty was the main attraction … I was mad about flying and applied straight away. I requested a transfer on several occasions, but I had to wait until 1917 before I was accepted.’ After basic training at Ambérieu, Benoit moved on to the naval school at Hourtin for specialist seaplane work: ‘The lake was 17 kilometres long and, with an instructor and a seaplane to myself, I could practise taking off and landing non-stop. After forty-eight hours they decided I deserved my wings.’ From Hourtin, Benoit proceeded to the bombing and air gunnery school at Saint-Raphaël and within a fortnight was a squadron commander at Bizerta.

Flying-boat crews faced a particular risk: if forced down, they landed at sea. With no wireless, their only option was to release their carrier pigeons or hope to catch the attention of a passing vessel. On 3 October 1918 Maître Guillaume Kerambrun had just returned to La Penzé after a four-hour patrol in poor weather when he was scrambled again: a German submarine had just been spotted off the north coast of Brittany. ‘The conditions are lousy,’ he was told. ‘You’re the senior pilot. It’s your job to get out there.’ He and observer Lieutenant de Vaisseau Latard de Pierrefeu took off in their Tellier, only for the engine to fail in mid-air. They managed to touch down safely but spent a further twenty-four hours in rough seas before a warship arrived to take them off.

Yet their ordeal was nothing compared to that endured by Enseigne de Vaisseau Jacques Langlet and Second Maître Maurice Dien, pilot and observer of FBA flying boat H.4. With their comrades in H.48, they left Toulon-Saint-Mandrier at 10.00 am on 2 July 1918 to escort a convoy inbound for Marseille, but ninety minutes later, some 30 nautical miles south of the Île de Planier, their engine began playing up. ‘[It] kept missing, then restarting,’ recalled Langlet. ‘We tried using the hand pump to repressurize the tanks but eventually it stalled.’

All they could do was touch down in the heavy seas, release one of their two pairs of carrier pigeons, each bearing a note of their position, and watch H.48 fly off to seek help. But the north-westerly mistral was growing stronger, driving them further from land and carrying off their sea anchor in the swell. They jettisoned as much as possible – bombs, radiator, magnetos – used rudder and ailerons to keep the nose facing into the wind and took it in turns to steer. Finally they opened their emergency rations. What a disappointment, recalled Langlet: ‘two mouldy ship’s biscuits (in pieces), a tin of pâté (spoiled, as we later discovered), two 20oz tins of corned beef (in good nick), two bars of chocolate (mouldy) and a bottle of rum. I was seasick until that night and Dien until the following day.’

By then the wind had strengthened further. ‘A dreadful sea with troughs at least 8 metres deep,’ reported Dien. ‘We’d taken on some water, but the lieutenant used the first-aid box as a baler…. We’d been drifting very rapidly south-east since 2 [July]. We hoped towards Corsica or Sardinia.’

Day three was just as bad: ‘Sea still rough. We took it in turns to sleep…. The bottle of rum slowly emptied. Very thirsty. No more biscuit. Just a few crumbs. All we had left were the two tins of “monkey”.’

Day four brought a change in the weather: ‘The wind eased and seemed to be backing west-southwesterly. But it was a variable breeze that drove us back over seas we’d already covered that morning…. I unscrewed the compass but the liquid inside was undrinkable. The lieutenant rinsed his mouth out with salt water. We each sucked a button, which produced a drop or two of liquid. By noon we were dying of thirst. The wind had dropped. The blazing sun burned the arms of my shirt, and a violent bout of sunstroke made me feverish. The compass [liquid] didn’t look too bad. I tried a drop. It was ghastly, but it did quench your thirst a little. We couldn’t be too far from land. There were butterflies round the plane.’

Throughout days five and six the calm and the heat continued unabated: ‘No wind. Light breakfast. Nothing to drink. Smoked a cigarette which made us thirstier still. An awful day. Made drowsy by the sun, I dozed on one of the wings and burned my arms. Always the same impossible dreams: a boat, land, water!

Langlet takes up the tale: ‘That night we thought we could see fires twinkling. Thinking we’d spotted a lighthouse, we launched several rockets, hoping that torpedo-boats would come for us. It was all a mirage! They were stars! We finished off the last of the rum. We could no longer moisten our lips or swallow. But on the morning of 7 July we managed to rig up something to distil seawater…. The results weren’t great, but gradually we increased the yield of each operation from a thimbleful to the size of a Madeira glass. That was how we survived, and it was all down to Dien’s skill and ingenuity. He’s a wonderful mechanic.’

With a breeze now picking up from the south, they rigged up sails using canvas torn from the upper wings. Day eight … day nine … steady progress northwards. Insects everywhere. Surely they must be nearing land? Hearing an aircraft engine, they lit a small fire and fired a Véry light – but no response. Then at 2.00 pm on day ten they finally sighted land. ‘The lieutenant pointed out a brown mass among the clouds that didn’t change shape as you looked at it,’ recounted Dien. ‘Definitely land. I piled on the sails. The wind was pushing us towards it, though not flat out, but things were definitely looking up. We’d fashioned a rudder out of an aluminium panel from the fuel-tank housing and we were almost sailing landward…. A fire, three bangs, no question this time. But then the wind veered and started pushing us parallel to the coast. I was too restless to sleep and watched the fires recede from view. At daybreak we could see a headland [Capu Rossu on the west coast of Corsica].’

Day eleven – and rescue at last. ‘Activity on the mountainside, then a small boat pulled out and drew alongside us. “Are you French?” was the lieutenant’s first question. We’d hauled down the flag from the upper wing just in case. They dragged us on board and ferried us ashore [where] intrepid Corsicans immediately surrounded us, lavishing upon us their island’s famous hospitality…. It was over! My strength failed me. I collapsed on the sand and woke to find myself surrounded by weeping women … fussing over me to an almost embarrassing degree. Then we were loaded on to donkeys and taken to Piana and a good bed where we slowly regained our strength…. The plane was dragged on to the beach. Poor old thing. We owed it a real debt of gratitude. It had carried us for 267 hours, the first three days in a terrible sea. I still wondered if it had all been a dream. If I wasn’t being cared for in Ajaccio and my burned arms weren’t hurting so much, I’d have thought it was just a nightmare.’

Back at the base the mood was sombre. At Toulon cathedral that morning their comrades had attended a memorial mass, and by evening the CO, Lieutenant de Vaisseau Samy Fournié, was busy drafting letters of condolence. Then an urgent telegram arrived: ‘Seaplane reported drifting 2 July reached land Gulf of Porto 13 July. [Pilot] and observer both safe and well.’ Champagne was poured and toasts drunk. ‘Should they have been getting the off-base subsistence allowance?’ asked the paymaster dryly. ‘Half-rate only,’ joked Fournié. ‘They already had accommodation!’ After the war Langlet went on to captain the merchant vessel Peiho; Dien pursued a distinguished career in civil aviation.

By November 1918 the naval aeronautical service contained 11,000 officers, petty officers and men – around a tenth of all navy effectives – operating some 700 seaplanes, 200 captive balloons and 37 dirigibles from thirty-six centres and satellite posts, with several hundred more in reserve. The balloons were eventually credited with locating sixty U-boats and destroying over a hundred mines, while the service as a whole was delivering bomb and torpedo attacks, attaining local air superiority in some sectors, and impressing many officers with its offensive potential, particularly in anti-submarine warfare. ‘A squadron without aviation’, concluded Capitaine de Frégate Henry de l’Escaille, later a leading figure in the aircraft manufacturing industry, ‘is a squadron lost.’ But the costs were high, with 195 deaths recorded among the 1,500 pilots and observers trained during the course of the war.