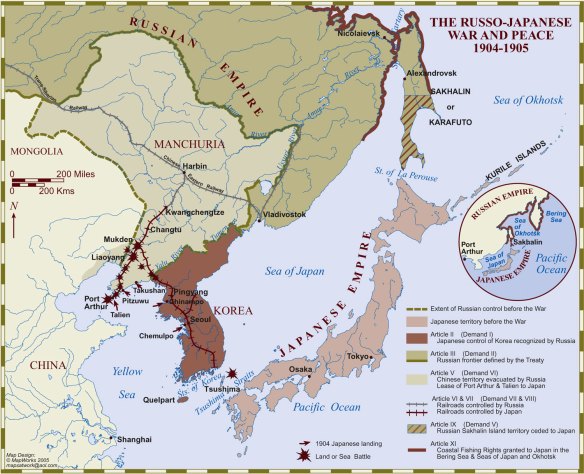

The end to Korea’s effective independence came as a result of the Russo- Japanese War. A major imperialist power in the age of imperialism, Russia took advantage of the retreat of Japan in 1895 to advance in northeast Asia. It concluded a secret treaty with China to build part of the Trans- Siberian Railway it was constructing across Manchuria. The Russians also acquired twenty-five-year leases on Port Arthur and Dalian, and began a program to build a rail line linking these warm-water ports to the Trans-Siberian. In 1900, Russian forces entered Manchuria during the Boxer Rebellion. These forces were supposed to be withdrawn after the rebellion ended, but in fact they remained there, alarming Britain as well as Japan. In 1902, to counter Russian expansion in the East, Britain abandoned its long-held policy of avoiding formal alliances by concluding the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Britain agreed to acknowledge Japan’s interest in Korea in exchange for Japan’s recognition of British rights and interests in China. With its position strengthened, Tokyo demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops from Manchuria. Russia, however, reneged on promises to do so. Instead, in July 1903, a small group of Russian soldiers entered Korea at Yongnamp’o, a trading port at the mouth of the Yalu, and started constructing a fort. At Japanese insistence, they withdrew. Many Japanese had hoped to work out an agreement with Russia—a free hand in Manchuria for Russia in exchange for a Japanese free hand in Korea—but nothing came of this. Instead Russia’s provocations were such that Japan decided to take military action to prevent Korea from falling into Russian hands. In February 1904, the Japanese carried out a surprise attack on the Russian naval facilities at Port Arthur.

Korea declared its neutrality in January 1904 in the wake of rising tensions between the two imperialist powers. When hostilities broke out, Japanese troops entered Seoul, as they had done at the start of the Sino-Japanese War, and compelled the Korean government to bow to its wishes. The Korean foreign minister signed a protocol in February that in effect made Korea a protectorate of Japan. It gave the Japanese government the right to take any necessary action to protect the Korean imperial house or the territorial integrity of Korea if threatened by a foreign power and gave the Japanese the right to occupy certain parts of the country. In another agreement signed in August 1904, Korea agreed to appoint a Japanese advisor to the Ministry of Finance and a non-Japanese foreigner recommended by the Japanese government to advise the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It also required Korea to consult with Japan before signing any treaties or agreements with other countries, or any contracts or concessions to foreigners. A Japanese, Megata Tanetaro, became financial advisor, and an American, Durham White Stevens, became the foreign affairs advisor. In effect, the Korean government had conceded control of its financial and foreign affairs to Japan. Meanwhile, a pro-Japanese association called the Ilchinhoe (Society for Advancement), under the leadership of Song Pyong-jun, was actively advocating the union of Korea and Japan. This group received support from nationalist, pro-expansionist groups in Japan. The purpose was to give an impression that the Japanese takeover of Korea had popular support among Koreans. Many Japanese nationalists became involved in the project to bring Korea under Japanese rule, sometimes working in tandem with their government, sometimes running ahead of it.

To the surprise of many observers and largely to the delight of the British and Americans, Japan emerged victorious in the war. Facing overly extended supply lines and revolt at home, Russia concluded the Treaty of Portsmouth with Japan in September 1905, with President Theodore Roosevelt acting as mediator. Russia withdrew from Manchuria, and Japan acquired Port Arthur and was now unchallenged in its efforts to achieve domination over Korea. The United States tacitly accepted the transfer of Korea to Japan in the Taft-Katsura Memorandum of July 1905. In this exchange of views between American secretary of war William Howard Taft and the Japanese prime minister Katsura Taro, the United States recognized Japan’s right to take appropriate measures for the “guidance, control, and protection” of Korea; in exchange, Japan recognized America’s position in the Philippines. Britain, renewing its alliance with Japan in 1905, also tacitly accepted Korea as being in Japan’s sphere. The way was diplomatically prepared for Japan to take a free hand in Korea.

In November 1905, Ito Hirobumi, one of the principal architects of Meiji Japan came to Seoul to conclude a treaty establishing a protectorate. On November 17, 1905, with Japanese troops displaying a show of strength on the streets of the capital, the Korean foreign minister, Pak Che-sun, signed what has been called the Protectorate Treaty of 1905. The acting prime minister, Han Kyu-sol, refused to sign it. This agreement transferred all foreign relations to Japan. A Japanese resident-general (tokan) was to be stationed in Seoul with direct access to the Korean emperor. According to the treaty, his role was to manage diplomatic affairs, but his authority soon expanded to include most aspects of the country’s administration. Beginning with the Americans, the international community closed its legations in Seoul, and the country was now only nominally independent. Most Korean officials such as Pak Che-sun, who became prime minister, simply accommodated themselves to the new reality. A few were despondent. Diplomat and official Min Yong-hwan committed suicide in protest; others went into exile. In reality, Korea was under Japanese control since the start of the Russo-Japanese War in early 1904, so the formal protectorate was not a sudden change or traumatic event but simply one in a series of steps by which Japan consolidated its rule over Korea. The process, however, did not end with the protectorate; rather, it was another step in Japan’s absorption of Korea.