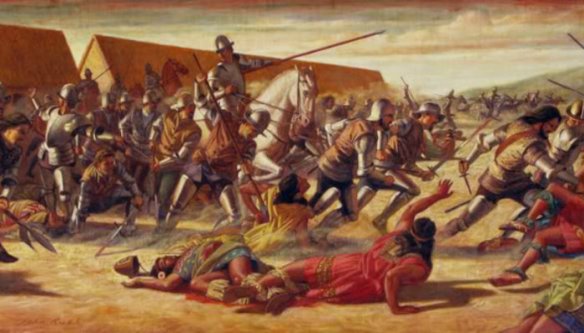

Spanish Conquest of Peru, 1532

Francisco Pizarro conquered the largest amount of territory ever taken in a single battle when he defeated the Incan Empire at Cajamarca in 1532. Pizarro’s victory opened the way for Spain to claim most of South America and its tremendous riches, as well as imprint the continent with its language, culture, and religion.

Christopher Columbus’s voyages to the New World offered a preview of the vast wealth and resources to be found in the Americas, and Hernán Cortés’s victory over the Aztecs had proven that great riches were there for the taking. It is not surprising that other Spanish explorers flocked to the area—some to advance the cause of their country, most to gain their own personal fortunes.

Francisco Pizarro was one of the latter. The illegitimate son of a professional sol- dier, Pizarro joined the Spanish army as a teenager and then sailed for Hispaniola, from where he participated in Vasco de Balboa’s expedition that crossed Panama and “discovered” the Pacific Ocean in 1513. Along the way, he heard stories of the great wealth belonging to native tribes to the south.

After learning of Cortés’s success in Mexico, Pizarro received permission to lead expeditions down the Pacific Coast of what is now Colombia, first in 1524–25 and then again in 1526–28. The second expedition experienced such hardships that his men wanted to return home. According to legend, Pizarro drew a line in the sand with his sword and invited anyone who desired “wealth and glory” to step across and continue with him in his quest.

Thirteen men crossed the line and endured a difficult journey into what is now Peru, where they made contact with the Incas. After peaceful negotiations with the Incan leaders, the Spaniards returned to Panama and sailed to Spain with a small amount of gold and even a few llamas. Emperor Charles V was so impressed that he promoted Pizarro to captain general, appointed him the governor of all lands six hundred miles south of Panama, and financed an expedition to return to the land of the Incas.

Pizarro set sail for South America in January 1531 with 265 soldiers and 65 horses. Most of the soldiers carried spears or swords. At least three had primitive muskets called arquebuses, and twenty more carried crossbows. Among the members of the expedition were four of Pizarro’s brothers and all of the original thirteen adven- turers who had crossed their commander’s sword line to pursue “wealth and glory.”

Between wealth and glory stood an army of 30,000 Incas representing a century- old empire that extended 2,700 miles from modern Ecuador to Santiago, Chile. The Incas had assembled their Empire by expanding outward from their home territory in the Cuzco Valley. They had forced defeated tribes to assimilate Incan traditions, speak their language, and provide soldiers for their army. By the time the Spaniards arrived, the Incas had built more than 10,000 miles of roads, complete with suspension bridges, to develop trade throughout the empire. They also had become master stonemasons with finely crafted temples and homes.

About the time Pizarro landed on the Pacific Coast, the Incan leader, considered a deity, died, leaving his sons to fight over leadership. One of these sons, Atahualpa, killed most of his siblings and assumed the throne shortly before he learned that the white men had returned to his Incan lands.

Pizarro and his “army” reached the southern edge of the Andes in present-day Peru in June 1532. Undaunted by the report that the Incan army numbered 30,000, Pizarro pushed inland and crossed the mountains, no small feat itself. Upon arrival at the village of Cajamarca on a plateau on the eastern slope of the Andes, the Spanish officer invited the Incan king to a meeting. Atahualpa, believing himself a deity and unimpressed with the small Spanish force, arrived with a defensive force of only three or four thousand.

Despite the odds, Pizarro decided to act rather than talk. With his arquebuses and cavalry in the lead, he attacked on November 16, 1532. Surprised by the assault and awed by the firearms and horses, the Incan army disintegrated, leaving Atahualpa a prisoner. The only Spanish casualty was Pizarro, who sustained a slight wound while personally capturing the Incan leader.

Pizarro demanded a ransom of gold from the Incas for their king, the amount of which legend says would fill a room to as high as a man could reach—more than 2,500 cubic feet. Another two rooms were to be filled with silver. Pizarro and his men had their wealth assured but not their safety, as they remained an extremely small group of men surrounded by a huge army. To enhance his odds, the Spanish leader pitted Inca against Inca until most of the viable leaders had killed each other. Pizarro then marched into the former Incan capital at Cuzco and placed his handpicked king on the throne. Atahualpa, no longer needed, was sentenced to be burned at the stake as a heathen, but was strangled instead after he professed to accept Spanish Christianity.

Pizarro returned to the coast and established the port city of Lima, where additional Spanish soldiers and civilian leaders arrived to govern and exploit the region’s riches. Some minor Incan uprisings occurred in 1536, but native warriors were no match for the Spaniards. Pizarro lived in splendor until he was assassinated in 1541 by a follower who believed he was not receiving his fair share of the booty.

In a single battle, with only himself wounded, Pizarro conquered more than half of South America and its population of more than six million people. The jungle reclaimed the Inca palaces and roads as their wealth departed in Spanish ships. The Inca culture and religion ceased to exist. For the next three centuries, Spain ruled most of the north and Pacific coast of South America. Its language, culture, and religion still dominate there today.