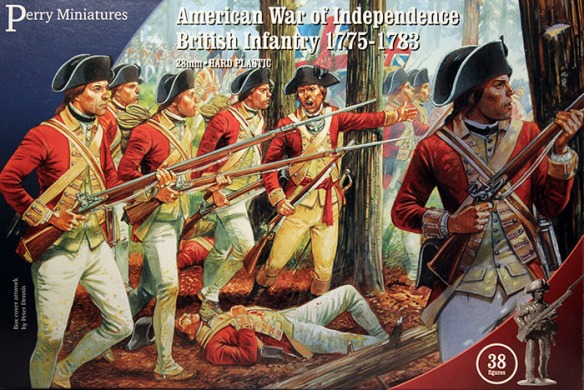

AW 200 American War of Independence British Infantry 1775-1783

AW 250 American War of Independence Continental Infantry 1776-1783

One of the questions that perpetually exercises historians is whether the Americans won the War of Independence or the British simply lost it. Certainly, especially at the war’s outset, the British possessed considerable advantages. London was the seat of the world’s richest, most powerful empire. Although she had jealous rivals in Europe, England was at peace and had been unchallenged since a series of victorious wars—including much North American combat—in the first half of the eighteenth century. Her ability to project power with a potent army and a magnificent navy was unmatched, and she had the 13 colonies strategically surrounded with outposts on the western frontier, as well as in Canada to the north and her Caribbean colonies to the south. England had suppressed rebellions before (admittedly closer to home, in Ireland) and successfully made war in North America. A considerable percentage of the American population—estimated at about 20 percent—remained loyal to the crown and at least a similar number were neutral.

Stacked against these favorable conditions were disadvantages. The British had to contend with a 3,000-mile lifeline across the stormy north Atlantic, upon which imperial forces depended for reinforcements, some logistical sustainment, and strategic direction. Internal lines of communication in America were no less fraught. While there were a handful of excellent ports, a paucity of good roads into the interior made the countryside poorly suited for maneuver and worse for logistics. As the war progressed, the British faced an increasingly aroused American populace, as well as the patriots’ European allies in what became a global struggle. In part, these last two developments reflected inept British political and diplomatic efforts, as well as the Americans’ more effective work in these spheres. Yet what hindered British more than any of these was the lack of a coherent strategy.

The objective was clear enough—end the colonial uprising and restore im- perial rule throughout the 13 colonies. Yet British leaders were divided to some degree as to whether the best method to achieve this was through conciliation or coercion. In London, policymaking responsibility lay in the hands of three individ- uals: King George III; his prime minister, Sir Frederick North; and the secretary of state for colonies, Lord George Germain, a former Army officer cashiered for misconduct. Historians have given all three exceedingly low marks for leadership ability and strategic insight. While a number of eloquent and influential British politicians—the best known being Edmund Burke and William Pitt—argued for a conciliatory policy and against the folly of violent repression, the three men at the top resolved on the latter.

While that would seem to have settled the matter, senior British officers in America had their own views. Both General Sir William Howe, who became the British commander in chief in America in October 1775, and his brother Lord Richard Howe, who assumed command of the British fleet in American waters in 1776, strongly favored conciliation. They remained at their respective posts until the middle of 1778 and their joint conduct of military operations reflected their ambivalence about prosecuting the war.

British command problems extended beyond the mixed feelings of the broth- ers Howe; indeed the entire chain of command was highly dysfunctional. The British violated the principle of unity of command in the American theater for much of the war by retaining a separate commander in chief for Canada, Sir Guy Carleton. General Howe’s deputy and eventual successor, General Sir Henry Clin- ton, while displaying flashes of professional talent, was congenitally incapable of taking risk or cooperating with either superiors or peers. Significant shortcom- ings in temperament and skill afflicted the other two senior British generals in America, John Burgoyne and Charles Lord Cornwallis, as well. Compounding the friction created by the collision of these bumptious egos, Germain back in London frequently bypassed the commander in chief to correspond directly with generals in the field. This fractured system led to considerable confusion and disastrously poor coordination, most significantly in the Saratoga and Yorktown campaigns.

Essentially, the British had two broad military schemas open to them. One was to be force oriented, that is to focus on the destruction of the main American armies, especially the one personally led by Washington. The other was to be terrain oriented—to seek to snuff out the rebellion through the control of key geographical points.

The first of these, in theory, offered the best hope to the British. In practice, destroying the enemy proved difficult to bring about for a number of reasons. For one thing, the Napoleonic battle of annihilation was alien to the Age of Reason and the eighteenth century way of war, which tended to be limited in scope and purpose. Then, during the war’s first half, General Howe was reluctant to essay a strategy of destruction due to his hopes for Anglo-American conciliation. For instance, in the fall of 1776 he routed Washington out of New York, but eschewed the opportunities afforded by his greater, seaborne mobility to cut the Americans off. Howe subsequently pushed the reeling patriots out of New Jersey, but again neglected to strike a death blow. But only part of this failure can be attributed to Howe’s personal disposition. Washington deserves at least as much credit for his skillful withdrawals.

As a result, the British ended up attempting, or at least considering, a variety of terrain-oriented schemes. The most basic was a naval blockade of American ports. Though seconded by a number of British strategists, it never got much purchase for a couple of reasons. First, despite its status as the world’s premier fleet, even the Royal Navy lacked the assets to close off completely America’s lengthy Atlantic seaboard. Further, strangling America would take time and could prove as costly to British merchants as to colonial traders, especially unpalatable for a war that was far from universally popular at home in England. Finally, in this preindustrial age, there really was not any necessary commodity that the Americans could not produce—or smuggle—in sufficient quantities to sustain the struggle.

Another tack, which the British pursued for the first part of the war, can be called the northern strategy. Here the British used the operational mobility afforded by their fleet to capture New York City as a base of operations. From there they rapidly conquered New Jersey and also Rhode Island, securing another naval bastion at Newport. A year later, they seized the rebel capital in Philadelphia, forcing the Congress into headlong and undignified flight. Almost simultaneously, though in totally uncoordinated fashion, they mounted a drive down from Canada with the goal of controlling the Hudson River valley and effectively severing the cradle of rebellion, New England, from the rest of the colonies. Successful in taking large cities, thwarted at Saratoga in the effort to command the line of the Hudson, this northern strategy ultimately failed to achieve the strategic goal of ending the rebellion. Indeed there is good reason to believe that even had the British achieved their aims in the Hudson Valley, they would have had insufficient resources to control all the key terrain necessary to cut off the colonies completely from each other.

The final terrain-centered strategy tried by the British came in the war’s concluding act, an invasion of the American south. In essence, the south always seemed like low-hanging fruit to some British strategists. Loyalist sentiment ap- peared stronger in the south, farther from the New England cockpit, and addition- ally the British could perhaps hope that southerners’ fear of hostile Indians and slave uprisings might keep them in check. Again British naval supremacy brought them swift control of coastal cities such as Savannah and Charleston. But though they won a string of tactical victories in the Carolinas and Virginia, none were strategically decisive. Meanwhile, rebellion thrived in the north and the British army in the south wore itself down chasing rebels until it became trapped itself at Yorktown.

The preceding catalog of British shortcomings and miscalculations might seem to indicate, in answer to the question posed at the beginning of this section, that the British lost the war more than the Americans won it. They certainly failed to break either the patriots’ army or their will. And they found it much easier to conquer territory than to control it. Such a conclusion, however, overlooks how American leaders and soldiers capitalized on the opportunities presented to them, and overcame their own deficiencies and errors in judgment. War is a dynamic contest of wills. The Americans proved eminently worthy of the victory they won.