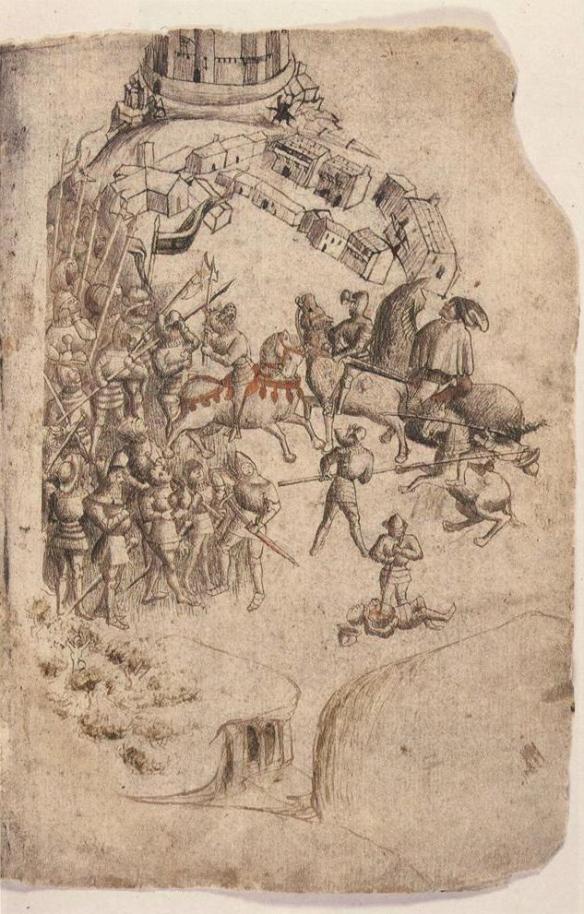

This depiction from the Scotichronicon (c.1440) is the earliest known image of the battle. King Robert wielding an axe and Edward II fleeing toward Stirling feature prominently, conflating incidents from the two days of battle.

One of Edward’s first acts as king was to set up a commission to enquire into the very abuses that had precipitated civil war in his father’s time, and he was assiduous in exposing and punishing corruption and misuse of office, provided that it was not his own. As many of the magnates claimed rights and privileges on the grounds that they had held them ‘since time immemorial’, Edward defined this as prior to the accession of Richard I in 1189. Thus, any claim less than eighty-five years old had to be proved by hard evidence, including the relevant documents, and even then was unlikely to be accepted. The administration of the realm was overhauled and an unprecedented flurry of legislation dealt with such matters as land tenure, debt collection, feudal overlordship, ecclesiastical jurisdiction, landlord and tenant relations, grants to the church and family settlements. The criminal law too was brought up to date and the statute of Winchester of 1285 insisted upon the community’s responsibility to lodge accusations of criminal conduct, ordered the roads to be improved and the undergrowth cut back to prevent ambushes by robbers, laid down what weapons were to be held by which classes to ensure the security of the kingdom, and made rape an offence for the king’s justice rather than a local matter.

It is as a soldier and a castle builder that Edward is best remembered, and the early years of his reign saw the subjection of Wales and the virtual destruction of the Welsh nobility. While contemporary English propaganda may have exaggerated, accusing the Welsh of sexual licence, robbery, brigandage, murder, every crime on the statute book and many not yet thought of, the Welsh princes had neither the administrative machinery nor the legal system to govern the country, and Edward’s campaigns of 1276 to 1284 brought the rule of (English) law and good (or at least better) government to a backward people. Edward’s announcement that the Welsh wanted a prince and that he would give them one in his eldest son displayed to the people on a shield is, of course, pure myth, although he did bestow the title of Prince of Wales on his heir. However brutal and legally dubious Edward’s subjugation of Wales may have been, modern Welsh nationalism has fed on a spurious legend of great warriors and an incorruptible native aristocracy that never existed. Then, in 1294, Edward’s fifty-fourth year and the twenty-second of his reign, came war with France resulting from Philip IV’s attempt to confiscate Aquitaine, simultaneous with a rising in Wales, and then a revolt in Scotland in 1297.

The preparations for the French war exposed the cracks in the feudal system of military service, which would linger on until the time of Edward III and briefly resurface under Richard II. Under it, the king had the right to summon those who held lands from him to give him military service for a specific period, usually forty days, although it could be extended, and these nobles with their retainers were supported by a militia of the common people, who again could only be compelled to serve for a specific period. Wars were expensive: the troops had to be fed, housed, transported and in some cases paid and armed. There was no permanent commissariat, and carts and horses and the supplies that they carried had to be bought or hired. It was generally accepted that the king could not finance a campaign of any length from his own income, and taxes and customs dues were usually agreed by an assembly of the great men of the realm, now increasingly being referred to as the parliament. Initially, such taxes were freely voted, but then, as Edward needed more and more money and more and more men to reinforce his garrison in Aquitaine, he began to take short cuts. Taxes were announced without consulting the parliament; the dean of St Paul’s is said to have died of apoplexy on hearing that the levy on the clergy was to be half of their assessed incomes; merchants took grave exception to the compulsory purchase of wool at less than market price, which the king then intended to sell abroad at a large profit. Royal agents who collected taxes and scoured the country for supplies and grain were said to be accepting bribes for exempting some men and to be keeping a portion of what they collected for themselves. Many magnates summoned for military service refused to go: when Edward told the earl of Norfolk that he had better go to Aquitaine or hang, he replied, correctly as it happened, that he would neither go nor hang. By the time that Edward decided to take the field himself and sailed for Flanders in August 1297, the country was on the brink of civil war and there were those who feared a repetition of the barons’ wars of Edward’s father and grandfather. What saved him was a rising in Scotland.

The Scottish problem was not new, but, up to the death of the Scots’ king Alexander III in a riding accident in 1286, relations had been reasonably cordial. William the Lion of Scotland had done homage to Henry II, and it was generally accepted that the English king was the overlord of Scotland, albeit that he was not expected to interfere in its administration. Alexander left no male heirs and his nearest relative was his six-year-old granddaughter, whose father was King Eric of Norway. Edward of England’s plan, which might have saved much subsequent Anglo-Scottish enmity, was to marry the ‘Maid of Norway’ to his eldest son, Edward of Caernarvon, later Edward II, but, when the maid died in the Orkneys on her way to Scotland in 1290, the inevitable rival claimants appeared from all corners of the country. Civil war was avoided by the bishop of St Andrews asking Edward I to mediate between the starters, soon reduced to two: Robert Bruce (originally de Brus) and John Balliol, both descendants of Normans and owning lands on both sides of the border – Balliol rather more than Bruce. By a process that came to be known as the ‘Great Cause’, which appears at this distance to have been reasonably fair and legally correct, Edward found in favour of Balliol, who was duly crowned in 1292.

At this point, Edward attempted to extend his influence into Scotland as he had in Wales, and his overturning of decisions of the Scottish courts and attempts to enforce feudal military service from Scottish nobles, which Balliol did little to resist, led to a council of Scottish lords taking over the government from Balliol in 1295 and making a treaty of friendship with Philip IV of France. This could never be acceptable to England, with the threat of war on two fronts, and in a lightning and exceedingly brutal campaign in 1296 Edward destroyed the Scottish armies and accepted the unconditional surrender of the Scottish leaders including Balliol. Had Edward reinstalled Balliol and backed off from insisting on what he saw as his feudal rights, all might have been well, but, by imposing English rule under a viceroy, Earl Warenne, with English governors in each district and English prelates being appointed to vacant Scottish livings, and by adding insult to defeat by removing the Stone of Scone, on which Scottish kings were crowned, to England, he ensured revolt was inevitable. It duly broke out in 1297 as Edward arrived in Flanders to intervene personally in the war against the French.

Almost immediately, all the resentment that had been building up against Edward for his unjust methods of financing the French campaign dissipated. War abroad against the French was one thing but revolt by what most English lords saw as English subjects was quite another. Robert Bruce, previously a loyal subject of Edward but dismayed by the failure to grant the throne to him, was easily dealt with by Warenne, but then a massacre of an overconfident English army at Stirling Bridge in an ambush skilfully conducted by William Wallace in September 1297 outraged and frightened the English government. Edward came to terms with Philip IV, returned from Flanders, and at the Battle of Falkirk in July 1298 slaughtered Wallace’s Scottish army. It was the bloodiest battle on British soil until Towton in 1461 but it was not decisive. Although the Scots would not for a long time risk meeting an English army in open field, their hit-and-run tactics would drag the conflict on until 1304, when the majority of the Scottish leaders came to terms with Edward. Wallace himself was tried as a traitor and suffered the prescribed punishment: hanged until nearly dead, then disembowelled and castrated, and his intestines and genitalia burned in front of him before he was decapitated and his body divided into four parts, a quarter to be exhibited in different cities while the head was placed on a pike above Tower Bridge.

The respite only proved temporary, however. Robert Bruce, who had initially revolted in 1297 but then changed sides and supported Edward’s subsequent campaigning, led another rising in 1306 and, having eliminated another claimant to the throne by murdering him, had himself crowned as king. More battles followed, and when Edward I died on his way to Scotland in 1307, exhorting his son on his deathbed to continue his conquest of the northern kingdom, the horrendous costs of warfare were revealed in the crown’s debts of £200,000, or £124 million at today’s prices.

If Edward I has been subject to historical revisionism, then none is necessary for his son. Edward II was every bit as unpleasant and incompetent as the chroniclers claim. Although he inherited his father’s commanding height and good looks and was a competent horseman, he had little interest in the other knightly virtues and corrupted the system of royal patronage. This latter depended for its success on the wide and reasonably fair distribution of land, offices and titles, thus retaining the loyalty of those who mattered, but Edward neglected the magnates who expected to be preferred and instead lavished favours and lands on his successive catamites.

Homosexuality was then a sin in the eyes of the church – it was equated with heresy – and generally regarded with horror by the laity. Still, Edward’s proclivities might have been tolerated if he had kept them as private as it was possible to be in a medieval court, but this he was unable to do. Some modern scholarship has suggested that Edward’s relationships were not sexual but actually a form of blood brotherhood, and it points to the fact that accusations of homosexuality against Edward were only hinted at during his lifetime and not made openly until after his death. Edward and both his favourites were married and produced children, but all three had to produce heirs and anyway it is not uncommon for homosexuals to engage in occasional heterosexual relationships. While at the time it was not unusual for men to share a bed without any impropriety (indeed, soldiers in British army barrack rooms were required to sleep two or three to a bed until well into the nineteenth century), it was certainly unusual that Edward chose to sleep with a man rather than his wife on the night of his coronation. That the magnates had their doubts about Edward from a very early stage is evidenced by their insertion of a new clause in the coronation oath, whereby he swore to uphold ‘the laws and customs of the realm’.

Edward’s first favourite, who had been part of his household since he was Prince of Wales, was Piers Gaveston, a Gascon knight and son of a loyal servant and soldier of Edward I. Knighted by Edward I and then advanced by Edward II to the earldom of Cornwall (a title normally reserved for princes of the blood royal), Gaveston was intelligent, good-looking, a competent administrator and excelled at the knightly pastimes of hunting and jousting. All might have been well if he could only have restrained his wit and avoided poking fun at the great men of the kingdom. Had he deferred to the nobility and worked at showing them that he was no threat (and he appears to have had no political ambitions), he might well occupy no more than a brief footnote in history, but, as it was, he could not resist teasing the magnates, to whom he gave offensive and often apt nicknames of which he made no secret. Thus, the amply proportioned earl of Lincoln was ‘burst belly’; the earl of Pembroke ‘Joseph the Jew’; the earl of Lancaster, the king’s cousin, the richest man in the kingdom and the proprietor of a large private army, ‘the fiddler’; and the earl of Warwick, who would ultimately be responsible for Gaveston’s premature demise, ‘the black dog of Arden’.

Not only did Gaveston make no secret of his deriding the great men, but he also publicly humiliated them by beating them in jousts and took a prominent role in the coronation that should have been filled by men of far higher status. Gaveston married the king’s niece, a union to which his birth did not entitle him, and, when Edward went to France to collect his own bride, he left Gaveston as regent. By his behaviour and by his position as the king’s principal adviser, Gaveston was bound to make dangerous enemies: he was exiled once by Edward I and twice by Edward II under pressure from the magnates, who threatened civil war if the favourite did not go. Then, in 1312, Gaveston’s return from exile for the third time did spark baronial revolt. He eventually fell into the hands of his enemies, principally the earl of Warwick, and, after a trial which was probably illegal, he was condemned to death and beheaded near Kennilworth on land belonging to the earl of Lancaster. As was the norm at the time, no one actually blamed the king for all the injustices and inefficiencies of his reign, but rather his evil counsellor – Gaveston – and Edward was then in no position to do anything about what he saw as the murder of his beloved Pierrot. Revenge was to come later.

Despite the removal of Gaveston, by 1314, baronial opposition to Edward’s rule, or misrule, was growing. Having ignored his father’s dying wish that he should complete the conquest of Scotland, Edward II had abandoned that nation to civil war and returned south. Now, hoping to restore the political situation at home by a successful war in Scotland, Edward summoned the earls to report for military service. The earl of Lancaster and a number of his supporters refused, on the grounds that Parliament had not approved the finance for the expedition, which was therefore illegal. Edward went ahead anyway and the result was a disaster when, at Bannockburn in June 1314, his army of around 10,000 was decisively defeated by a much smaller Scottish army commanded by Robert Bruce. Edward fled the field (to be fair, he wanted to stand and fight but his minders would not have it) and his army collapsed with perhaps a third becoming casualties. Disaster though it undoubtedly was for Edward, the battle was the trigger for a root-and-branch reform of the English military system which, as we shall see, would contribute much to the superiority of English arms in the Hundred Years War.

As the Scottish war dragged on without any prospect of a successful end, Edward’s position weakened further. Scottish raids into northern England were increasingly ambitious, Berwick-upon-Tweed was under siege yet again, and there was revolt in Wales. To make matters worse, new favourites began increasingly to engage Edward’s attention and to receive favours from him. The Despensers, father and son, both named Hugh, were rather better bred than Gaveston had been, but were actually more of a threat, being even more avaricious than the previous royal pet and, in the case of Hugh the Younger, possessing both political ambitions and the ability to pursue them. There is less evidence for a homosexual relationship between Edward and Hugh the Younger than for one with Gaveston, but there can be little doubt that the friendship was rather more than just the comradeship of men both in their thirties.

As it was, the Despensers’ methods of increasing their holdings of land varied from blackmail and intimidation of the courts to the threat and sometimes use of force and outright theft. In this, they particularly upset the Marcher Lords, who found estates in Wales and on the border that should have gone to them being acquired by the Despensers, while early on Hugh the Younger upset the earl of Lancaster when he was granted a potentially lucrative wardship which Lancaster had attempted to obtain for himself. Antagonism towards the Despensers exploded in 1321 when the Marcher Lords, aided by Lancaster and including one Roger Mortimer, attacked Despenser lands and properties. In Parliament in London, the lords laid the usual charges: removal of competent officials by the Despensers and their replacement by corrupt ones; refusing access to the king unless one of them was present; misappropriating properties; and generally giving the king bad advice. Edward, backed into a corner and faced with the united opposition of so many, had little choice but to agree to Parliament’s demands and the Despensers were duly exiled.

Now began Edward’s only successful military campaign of his entire reign. Lancaster, for all his titles and riches, was not a natural leader, a competent general or politically astute; he was indecisive and he too had his enemies. Once away from the London parliament, Edward recalled the Despensers, besieged and took Leeds Castle in Kent, executed the commander and his garrison, and marched north. Lancaster too moved north, possibly to seek sanctuary with the Scots, and on 16 March 1322 found his way barred by a royalist army at Boroughbridge, which held the only bridge over the River Ure. Unable to force the bridge, the earl of Hereford being killed in the attempt, and prevented by royalist archers from crossing at a nearby ford – lessons that would also be relevant to the great war that was to come – Lancaster’s army melted away and the earl himself surrendered the next day. Tried as a traitor at Pontefract, Lancaster could have expected to have been pardoned with a fine or exiled at worst in deference to his royal blood (he was a grandson of Henry III), but now it was payback time for Gaveston, and the only concession to Lancaster was that he was beheaded rather than hanged, drawn and quartered. Despite Lancaster’s unpleasant traits, such was the unpopularity of the king and the Despensers that a cult rapidly grew up and royal guards had to be posted over Lancaster’s tomb to prevent miracle-seekers approaching it. Now that he had dealt with Lancaster, Edward’s revenge on the other rebels was bloody: eleven barons and fifteen knights were indeed drawn, hanged and quartered, four Kentish knights were drawn and hanged but not quartered, in Canterbury, and another in London, while seventy-two knights were imprisoned. From now until 1326, the Despensers’ power, wealth and influence increased: their mistake, and the cause of their ultimate downfall, was in attracting the opposition of the queen.