In Yorkshire a neutrality pact was the product of deep divisions rather than of local unity. Early in October prominent Yorkshire gentlemen concluded a treaty of neutrality. Ferdinando, Lord Fairfax, who had raised forces on behalf of Parliament, and the Earl of Cumberland, the King’s commander in Yorkshire, were both signatories. Ferdinando’s father had fought in the continental wars and was a committed supporter of the military defence of international Protestantism. He had been disappointed in Ferdinando’s martial qualities after he sent him to the Netherlands in the 1630s, but Ferdinando was to prove a successful parliamentary general. His son, Sir Thomas, had been schooled in the virtues of armed Protestantism by his grandfather more than by Ferdinando, and was to rise to the very top of the parliamentarian armies in 1645. The desire to exclude the war from Yorkshire was thought by some to be improper. Fairfax had insisted that it be approved by Parliament and Sir John Hotham, an old rival of Fairfax, denounced it in print as an affront to the judgement of Parliament. His son went further, taking armed men to the walls of royalist-held York, and capturing the Archbishop’s seat at Cawood Castle on 4 October. The following spring both Hothams deserted the parliamentary cause, and their attitude to this neutrality deal may have reflected hostility to Fairfax as much as it did commitment to parliamentary authority. It also reflected how exposed the Hothams would have been by a neutrality pact – they had ventured far more than the Fairfax family at this point, not least in refusing the King entry to Hull.

Whatever the local politics of neutrality in Yorkshire, it did not work. Parliament condemned the treaty, and a military contest for control of the county ensued. The Earl of Newcastle, a regional magnate of considerable influence, was able to bring men south, while the Fairfaxes were able to draw on considerable support in the clothing towns of the West Riding. Hull, perhaps the best-fortified town in England, was securely in parliamentary hands. The East Riding was in the control of the Hothams, on behalf of Parliament, but their relationship with the Fairfaxes was not easy. It seems equally true that neutrality reflected deep divisions in Lancashire and Cornwall.

The varieties of neutralism – genuine refusal to join either side, or more prudential calculations about how to limit the impending war – were also visible in the towns. Towns were very obvious military targets, and faced the possibilities of long-term garrisoning and sieges. Although some towns were well-fortified most were not, and there was a clear incentive to submit to the nearest strong military force. Bristol, for example, seems to have been largely non-aligned prior to 1642, pursuing primarily economic grievances and allowing, rather than seeking, parliamentary occupation. Worcester’s royalism was similarly passive, York was not clearly committed and even Oxford, soon to become the royalist capital, owed that position to the University more than to the citizens. Nonetheless, it does seem that on balance Parliament enjoyed more support from the towns: in October 1642 all the major towns were in parliamentary hands with the exception of Chester, Shrewsbury and Newcastle. In Coventry an attempted royalist occupation led by the King himself was defeated by citizens in August, an event crucial to the course of the war in Warwickshire. This citizen activism tipped the balance between rival groups in the governing elite, a balance which had until then pointed towards neutralism.

One particular special case was the English colonies abroad. Their legal existence depended on the prerogative and, unlike most other areas of English jurisdiction, there was a close relationship between their legal powers and their actual existence: robbed of the protection of a charter they might disintegrate, or disappear altogether. All strands of opinion were represented, but perhaps a poll of settlers in the New World might have revealed a stronger backing for further reformation than was evident in the Old World. Nonetheless, as corporate entities the colonies were not free to take sides. Thus, although New Englanders fought as individuals, either in the armies or in the pamphlet exchanges, their colonial governments tried to remain uncommitted as corporate entities. Virginia, under the governorship of Sir William Berkeley, kept the royalism of its nascent elite undeclared until after the regicide in 1649. Even after that, a formula was found for an accommodation with the King’s killers.

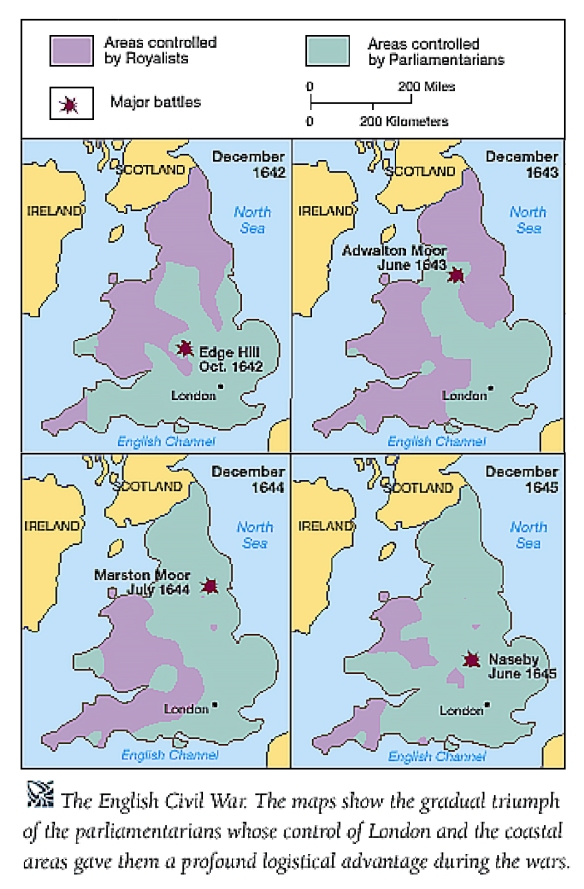

By the autumn, in England, the military geography was fairly clear. Waller had taken Portsmouth on 7 September and the south of England had been secured for Parliament, with the exception of Sherborne Castle, which was in the hands of Hertford. East Anglia, subsequently notoriously parliamentarian, in fact had a more complex history in 1642. A group of gentry tried to get the support of the Grand Jury at the Suffolk assizes for a neutralist petition and both the Commission of Array and Militia Ordinance were left unenforced for much of the summer. There it may have been fear of social disorder which created this attitude among the gentry, and once parliamentarians had taken the initiative support for them posed less of a threat to local social order than contesting control. Essex, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Norfolk also saw attempts to prevent political dislocation. The royalists had control of Cornwall, Wales and the north. Lancashire was disputed territory, thanks to the resistance to the royalists of districts around Manchester. Yorkshire was in parliamentary hands but the Earl of Newcastle had secure control further north. Parliament had Portsmouth, Hull, London, Bristol and many more minor, and less defensible, towns.

Military and political control of a territory might conceal divisions in local opinion, and such control was rarely treated as unquestioned by either side. The Marches of Wales became renowned as heartlands of royalism, but there is little sign of royalism prior to the mobilizations of 1642, except perhaps in Herefordshire – it seems to have been a product of mobilization rather than a cause of it. In Cornwall and Kent, as we have seen, it was decisive action by Hopton and Sandys not uniform local support that underpinned military command. Even in London there were divisions of opinion. Given these histories, it is no surprise that maintaining control over territory was an important part of the military history of the war, as much so as the grand marches which form the meat of most military accounts of the war.

Finally, in the late summer, the field armies gathered. When Charles raised the royal standard on Castle Hill in Nottingham on 22 August, summoning his loyal subjects to his side, few people came. The small crowd flung their caps loyally in the air and cheered ‘God save King Charles and hang up the Roundheads’, but the standard blew down in the night and, according to Hyde, ‘a general sadness covered the whole town’. It was the culmination of a disappointing peregrination of the Midlands. At Lincoln, Charles had been met by 30,000 people anxious to get a glimpse of their king and to listen to the loyal addresses, but there were few troops from Lincolnshire to see the standard on 22 August. The gentry of Yorkshire and the burgesses of Coventry seem to have been equally lacking in fighting spirit. At Nottingham Charles may have had 2,000 horse, but he had very few foot and by early September he may have had only a quarter as many troops as Parliament had managed to move to Northampton.

Disappointed, the King set off for Shrewsbury, disarming the Trained Bands as he went. He had already taken the weapons of the Lincolnshire Trained Bands on 16 August. Here too war was raising the stakes in mendacity, since he had promised that he was fighting to defend property. Equally, or even more alarmingly, local communities were being stripped of their defensive arms after fifteen months of very public anxiety about popish plots. West of the Pennines, however, his fortunes improved and an army gathered. The Earl of Derby successfully recruited in south Lancashire, perhaps coercively. Troops began to arrive from north Wales and the Marches in the last week of September and into mid-October. On 23 September he was given a heartwarming welcome at Chester and, if Strange’s recruiting methods were coercive, it seems that Sir Edward Stradling and Thomas Salusbury were able to draw on deep wells of support in Wales. The troops were also paid, of course, and this may have helped – at Myddle Hill, in Shropshire, Sir Paul Harris was offering a very generous 4s 4d per week, and he found twenty volunteers at that price. In Monmouthshire it was the prestige and power of the Earl of Worcester that delivered troops to the King. Despite these more hopeful signs Charles still felt he needed to relax the policy on Catholics. He had officially declared that ‘No papist of what degree or quality so ever shall be admitted to serve in our army’, but in a letter of 19 September to the Earl of Newcastle he took a more pragmatic line:

this rebellion is grown to such a height that I must not look of what opinion men are who at this time are willing and able to serve me. Therefore I do not only permit but command you to make use of all my loving subjects” services, without examining their consciences – more than their loyalty to us – as you shall find most to conduce to the upholding of my just legal power.

Newcastle’s army was renowned as papistical through the rest of the war.

Parliament’s success was much more immediate. In May the earls of Essex, Holland and Northumberland had attended a muster of 8-10,000 men in London. Subsequent attempts to enforce the Militia Ordinance were largely successful, particularly in the south-east. A committee for printing had been re-established in June 1642 which seems to have been energetic in publicizing the cause – there were 9,000 copies of a declaration of 4 July against the Commission of Array for example. The House of Commons itself failed the test of raising money on the Propositions, but it was successful in Hertfordshire and elsewhere, funding a productive drive to recruit volunteers in London and the south-east. On 8 August six bands of foot (4,800 men) set out for Warwick, accompanied by eleven bands of horse. When the Earl of Essex left London to join the army on 9 September he was watched by the full City militia, in arms. When he got to Northampton he was at the head of 20,000 men. This might have threatened a quick resolution given the unimpressive response to royalist recruiting at that stage. Sir Jacob Astley, the King’s infantry commander, was said to have been worried that the King was so poorly supported that he might be ‘taken out of his bed if the rebels should make a brisk attempt to that purpose’.

It is difficult not to think that Charles had the worst of all this. Petitions for accommodation between King and Parliament, and of loyalty to bishops, had come in from all around the country, but the King struggled to find men willing to fight for him in the Midlands. West of the Pennines he had more success, although it is difficult to see this as building on a long-term commitment to the cause, at least in most of the Marches. Elsewhere royalists manoeuvred, with mixed success, for local control. The success of individuals established the roots of regional royalist armies in the north and west but the King’s own field army was slow to build in the Midland counties. It created a federation of regiments under particular commanders as much as an integrated army. A map of military outcomes – strongpoints and towns held, musters achieved, armies assembled – is probably not a map of enthusiastic royalism. For both sides mobilization through print, preaching and the use of local institutions as a platform for partisan politics had been crucial. There were more musters by the authority of the ordinance than the Commission of Array, and petitions in support of Parliament were offset more by petitions for accommodation than by positive support for the King against Parliament. There were plenty of signs of reluctance to go to war, but far fewer than many people thought Parliament should concede.