By now war in the air had moved from duels between single aircraft to large formations contesting air superiority over segments of the front in swirling combat. On 30 April the Germans put up two large groups of twenty aircraft from four different squadrons and shot down six British aircraft flying in smaller formations. Out of these large groups of Albatros, most of the planes painted in bright, colorful designs, emerged what the British later called the ‘Richthofen Flying Circus’. But German superiority did not last. Two factors began to turn the situation around in May 1917 for the Royal Flying Corps. British aircraft production was finally reaching significant levels. In January and February the Corps had received 250 new aircraft. In the period March-April the number increased to 612; and in May-June to 757. But it was more than a matter of numbers. The aircraft delivered in late spring represented a new generation of aircraft, the ‘fourth generation’, as one historian designated them. Aircraft like the Bristol F. 2B, the SE 5a and the Sopwith Camel soon put the German Albatros, even with their better trained aircrews, at a disadvantage.

The decline In British casualties reflected these trends: in April the British suffered 316 casualties among their air crews in approximately 30,000 flying hours of operations over the Western Front. In May the British increased their flying hours by 25 percent, but saw a drop in casualties to 187; and in June the casualties dropped to 165. With better aircraft and greater numbers the British pressed hard on the German fighter forces, which also had to contend with the French. While the Germans held their own in a defensive sense, they could not match what the British put into the air until early 1918. The creation of the ‘Richthofen Flying Circus’ – originally based at Courtrai – allowed the Germans to concentrate greater numbers on small sectors of the front than their British opponents did and thus mitigate their growing technological inferiority. In The Great War in the Air, John Morrow records that Richthofen himself wrote to a friend in early July: ‘You would not believe how low morale is among the fighter pilots presently at the front because of their sorry machines. No one wants to be a fighter pilot any more.’ The greatest difficulty the Germans confronted in 1917 was the fact that they were steadily losing the quantitative race to Allied air forces. German industry had done wonders in the quantity and quality of weapons it turned out, and mobilization of German industry had proceeded more quickly than it had with the British. In 1914, the German aviation industry had delivered 1,348 aircraft to the army; in 1915 the number rose to 4,532. But the Germans were confronting a world-wide coalition that, in economic terms, by mid-1915 included the Americans as well.

The difficulties under which the German air units were operating showed clearly in summer 1917. In reply to Richthofen’s gaggles of aircraft, the British were putting formations of sixty fighters up over Flanders. As the French were in no position to conduct major military operations after the mutinies of May, the Americans remained in general disarray and the Russians were obviously on their way out of the war, the British carried the weight of the Allied effort in summer 1917. Unfortunately, Haig botched things. After the successes of Arras and Messines, there was some reason for optimism. But neither Haig nor his staff had developed a clear understanding of the major changes that were occurring in the tactics of the war. Moreover, with the help of a sycophantic and dysfunctional staff, Haig had lost touch with the sharp end of war. Thus, as his diary underlines, he had little understanding of the catastrophe that enveloped British forces engaged in the battle of Passchendaele. By 1917 the BEF had not yet reached a level of tactical sophistication which would bring great operational success. But Haig exacerbated the BEF’s weaknesses by picking a location (Flanders) and a time of year when weather and geography made prospects hopeless.

On 1 August 1917 – after two weeks’ preliminary bombardment that thoroughly alerted the Germans – the British threw their forces (as well as those of the Dominions) into a meat-grinder battle, the conditions of which were unimaginable except to those who were engaged in it. Haig’s chief of staff, Lancelot Kiggell, exclaimed in November after visiting the front lines for the first time, ‘My God, did we send men to fight in that?’ The conditions of the battle minimized the changes in artillery that emphasized indirect controlled fire, as well as the potential of the Royal Flying Corps, despite its improvements in both its quantity and its quality.

When weather conditions in Flanders were suitable, British aircraft carried out attacks on targets in the German rear areas – airfields, railroad stations and trains. They also attacked German front-line positions directly. British ground-attack aircrews were not as well trained or prepared as their German counterparts. Given a flying speed of approximately 100 mph, the casualties from German ground fire were high. Arthur Lee was the only one of three flight commanders left within a week after his squadron began such attacks. He himself was shot down on three out of his first seven sorties, but in each case crash-landed his shot-up aircraft, within British lines.

With the dismal failure at Passchendaele Haig was in serious political trouble at home. Perhaps for this reason, perhaps because he had been a great supporter of tank development throughout the war, in late November 1917 Haig authorized an attack at Cambrai that relied heavily on the tank. There would be no preliminary bombardment; rather, the planners relied on the tanks and a heavy bombardment just prior to zero-hour to get the infantry across the killing zone and into the enemy’s defensive system. The attack succeeded beyond Haig’s wildest expectations. In one day it gained as much territory as the Passchendaele offensive had captured in three-and-a-half months. DH 5s directly supported the tanks, attacking German artillery positions which threatened the advancing tanks, while attack aircraft severely impeded German defensive efforts even when the tanks had broken down or been destroyed.

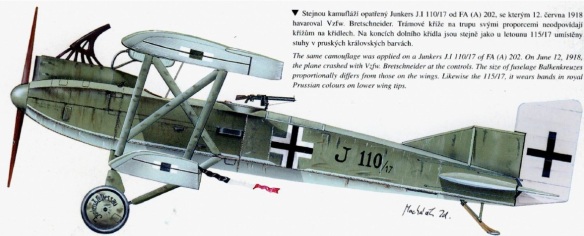

One week later a German counter-attack drove the British back from their gains with a well-executed, combined-arms, infantry-artillery attack based on exploitation, initiative and speed. Here again, close air-support aircraft substantially aided the Germans. In this case, some of the German aircraft were the new Junkers J.I, an all-metal, armored attack aircraft the Junkers firm had designed especially for the ground-support mission. The German counter-offensive, based on tactical rather than technological innovation, underlined how the pace of innovation on the Western Front had picked up since the war’s early years. In effect the Germans were on the way to inventing modern warfare.