The Albatros German fighter, supreme over the Western Front, 1916-early 1917.

In September 1916 the pendulum of the air war began to swing back towards the Germans. Boelcke returned to active duty on the Western Front in the desperate struggle on the Somme; he resumed his efforts to create a more coherent approach to air tactics by inculcating his precepts into the minds of those flying under his command. There were those like Rene Fonck who, because of their remarkable eyesight and reflexes, could kill at great distances. Fonck himself honed his natural abilities by potting away at coins tossed in the air. But Boelcke understood that most fighter pilots lacked such skills, and therefore needed closer ranges. As Fonck’s colleague Alfred Heurtaux inelegantly put it, shooting down aircraft was like shooting ‘a cow in a corridor’. By late 1916 air-to-air combat was no longer an affair of single pilots; it had turned into a contest of larger and larger groups of fighter aircraft working together. The French had started the trend at Verdun, but in September Boelcke and the Germans created Jagdstaffeln (fighter squadrons) whose business was to drive enemy fighters out of the sky so that they could not disturb German reconnaissance aircraft.

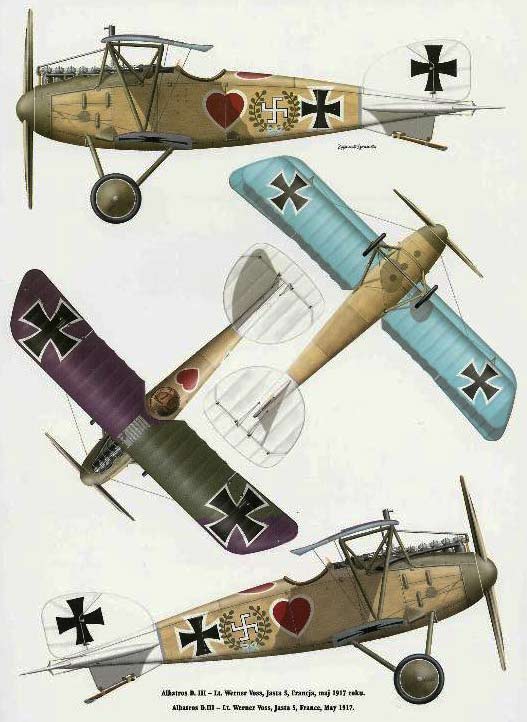

The Germans were considerably aided in their efforts by the introduction of the Albatros D.III. Superior to everything in the Allied inventory until the arrival of the Camel in mid-1917, the Albatros provided Boelcke and his pilots a better opportunity for executing the new tactics. The result was that the Royal Flying Corps suffered increasingly heavy losses as the Somme battle burned itself out. Still plagued by a weak training program, the life expectancy of RFC aircrews had dropped to less than a month by November 1916. The Germans also suffered serious losses since they possessed so few Albatros planes. Boelcke himself was killed in a mid-air collision with another pilot at the end of October. The Germans held a great funeral for their fallen hero in Cambrai cathedral.

While Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, sought the final decisive push on the Somme (not, in fact, to come for another two years), French troops under command of General Robert Nivelle attacked the German positions at Verdun and regained all the territory lost in that battle. Nivelle’s success resulted from the introduction of innovative combined arms tactics, which the French had been working on over the past two years – admittedly at heavy cost. Aircraft support with reconnaissance and artillery spotting had been an integral part of the evolution.

Shortly after the Nivelle’s success, Marshal Joffre finally fell from his position as French commander-in-chief. Petain was his obvious replacement, but his dour and pessimistic nature failed to recommend him to politicians, who were desperate to find a solution to the disastrously costly conflict. So they selected Nivelle, and he responded by claiming that he had discovered the method that would achieve decisive success in spring 1917. In fact, Nivelle’s offensive might well have achieved a major success except for three factors. The first was that the Germans had changed their entire defensive scheme. Over fall and winter 1916-17 they created the tactics and doctrine for a defense in depth – a system that took the great bulk of their infantry and artillery out of range of enemy artillery. Strong points and machine-gun nests, manned by the best troops in the German army, would now break up and dislocate Allied attacks, while the bulk of German infantry awaited the best moment to counter-attack. The new system was deeper and more flexible, and represented a tactical system against which the French had no experience. The second factor lay in the German withdrawal from the positions they had held for the first two years of the war to better sited and prepared positions.

The third factor had to do with the situation in the air. In April 1917 German superiority with the Albatros reached its height at the moment when the Nivelle offensive along the Chemin des Dames began. Consequently, aided by an early warning system based on reports from the anti-aircraft units, German fighter squadrons received timely warnings of French air operations. Their response virtually shut down French reconnaissance and artillery observation flights; the Germans also inflicted substantial damage on French balloon units spotting for the artillery. Thus, French infantry went over the top with little intelligence on German defenses, while the Germans were well informed on what the French were doing.While the loss of air superiority by itself was probably not decisive, it certainly exacerbated French difficulties along the Chemin des Dames. The failure of the Nivelle offensive, with heavy losses, came close to causing Allied defeat as mutinies broke out throughout the French army.

If April 1917 was a bad month for the French, it was a good month for the British army in its limited offensive in front of Arras. But the month was a disaster for the Royal Flying Corps – it was known as ‘Bloody April’ in recognition of the losses that enveloped British flying units. Trenchard’s constantly aggressive policies, whether his air units had the advantage or not, resulted in such high losses that the training establishment in Britain never caught up with the demand. As a result, British fliers, as had been the case in 1916, were still arriving on the Western Front with substantially fewer training hours than their German opponents; new pilots in May 1917 appear to have had less than twenty hours flying time – an improvement over 1916, but not much. One observer noted that many could not fly, much less fight. As a result the new arrivals had little chance to gain the experience required for survival in the killing arena of air-to-air combat.

Worse still, the British planes were distinctly inferior to the Albatros, which predominated in the German units opposite. Manfred von Richthofen commanded Jagdstaffel11 on the Flanders front and was at the height of his skill as a fighter pilot. Over the course of the month, Richthofen shot down twenty-one British aircraft, including four on the 29th alone. Between 4 April and 8 April the Royal Flying Corps lost seventy-five planes in combat, with nineteen aircrew killed, thirteen wounded, and seventy-three missing. The situation did not improve over the course of the month. Flying obsolete aircraft, British pilots were committed to an operational approach that condemned them to seek out enemy aircraft aggressively, while the Germans could pick and choose where to fight. Those flying in particularly obsolete aircraft, such as the Sopwith 11/2 Strutters and the Nieuports, were slaughtered. In his book The Rise of the Fighter Aircraft, 1914-18, Richard P. Hallion quotes one formation commander who exclaimed, after losing two aircraft out of his flight of six Strutters (the other four were all damaged: ‘Some people say the Sopwith two-seaters are bloody fine machines, but I think they are more bloody than fine!’

In addition to these successes, the Germans were expanding their air operations to include a significant innovation: close air support. While both the British and French had launched a number of attacks against railroad stations, bivouacs, and other rear-area targets, no one had yet made major efforts to support the infantry across the killing zone with aircraft. In the Arras battle the Germans introduced bombers to support their infantry with machine-guns, grenades and bombs. At Messines in early June these aircraft held up a successful British advance that was rolling forward after the explosion of a massive mine had destroyed most of the main German defensive positions.