The Tanks at Cambrai

The progress of the war, as the autumn of 1917 advanced, was depressing from the point of view of the Allies. The campaign in the Ypres Salient was grinding on at terrible cost, the Russians, embroiled in revolution, were no longer reliable allies and the Italians had suspended offensive action. It seemed an excellent time to revive a plan that had been put forward earlier in the year for a tank raid south of Cambrai.

The terrain near Cambrai, firm chalk-based country, was much better suited to tanks and the sector was lightly defended. Colonels Ernest Swinton and J.F.C. Fuller argued for massed formations of tanks on suitable terrain and the idea was finally accepted by General Sir Julian Byng of Third Army. He took the concept as far as breaking through the Hindenburg Line between the unfinished Canal du Nord on the west and the Canal du St Quentin on the east in the area south-west of Cambrai, capturing that town and Bourlon Wood, which gave an overview of the German-held country beyond, and, what was more, to exploit that with a breakthrough in the direction of Valenciennes.

Byng placed his IV Corps on the left with the 36th (Ulster), 51st (Highland) and 62nd (West Riding) Divisions, 1st Cavalry Division and 1st Tank Brigade. III Corps, on the right, had 6th, 20th, 12th and 29th Divisions and the 2nd and 3rd Tank Brigades. There were nine tank battalions in all with 378 tanks while another fifty-four machines were held in reserve. Most were equipped with fascines, great bundles of wood carried on their roofs to be dropped into enemy trenches and permit the machines to cross. Some tanks were equipped as wire cutters and others as mobile radio stations or supply vehicles.

A second, and less remarked on, aspect of the planned attack was the use of artillery as arranged by Brigadier General H.H. Tudor. He decided there should be no preliminary bombardment, thus gaining both surprise and unbroken ground, and that predicted fire should replace registration. Registration was a system of experimental firing at the intended target to work out the difference between the laying of a gun according to theoretical calculation and actual experience. Predictive firing meant testing the gun elsewhere to establish its deviation from its theoretical performance. It would then be possible to open fire accurately on a target located on a map.

At 0620 hours on 20 November the artillery opened fire and the tanks moved forward. The infantry followed, closely in all cases except for the 51st (Highland) Division. Their commander, General G.M. Harper, thought the tanks would attract German artillery fire and thus put his men in peril. They were ordered to hang back. The bombardment was fairly effective, but the British predicted fire had failed to take account of variations in the quality of the ammunition or of muzzle velocity variations for each individual gun. Surprise was, however, complete. The tanks worked in groups of three with the advance tank crushing the enemy wire, then turning left and opening fire on the first trench while the next tank came on to drop its fascine into it before crossing and opening fire on the second trench. The third tank then dropped its fascine and covered for the first tank to come through and bridge the third and last trench of the line; then off they went to knock out the strong-points to the rear. On the right, III Corps reached all of its objectives that day, getting as far as the St Quentin Canal south of Crèvecoeur and supporting crossings at Masnières and Marcoing. On the extreme left the 62nd (West Riding) Division struck north as far as the Bapaume to Cambrai road. Between these two, progress was held up. The unsupported tanks climbed rising ground south of Flesquières and came under fire from field guns of the German 54th Reserve Division. Outranged, and with no covering rifle or machine-gun fire from the 51st (Highland) Division to distract the gunners ahead, the tanks were knocked out one after the other. The delay allowed the covering barrage to move on and left the Highlanders without support from the guns. It was not until the next day that the 51st took Flesquières and pressed on to Fontaine Notre Dame on the flank of Bourlon Wood. Haig wrote in his diary on 22 November:

On the ridge about Flesquières were a dozen or more Tanks which were knocked out by artillery fire. It seems the Tanks topped the ridge and began to descend… all the personnel of a German battery … fled. One officer however was able to collect a few men and with them worked a gun and from his concealed position knocked out Tank after Tank … This incident shows the importance of infantry operating with Tanks at times acting as skirmishers to clear away hostile guns and reconnoitre.

The planned cavalry breakout could not take place as they had been too far in the rear on the first day and the Germans acted quickly to close the gap smashed in their line. The Germans had seven divisions at Cambrai by 26 November and pressure was mounting. On 30 November, the Germans counter-attacked not only in force, but using the penetration tactics developed on the Eastern Front at Riga and proven in Italy at Caporetto. The barrage began at 0800 with a high proportion of gas shell and the masses that had been rushed into the sector, an additional thirteen divisions in four days, allowed an eleven-division assault. The assault forced the abandonment of Bourlon Wood by 4 December and, after counter-attacks by the Guards Brigade to regain Gouzeaucourt on 30 November and 1 December, the eastern flank stabilised with the Germans having gained just about as much ground here as the British had in the north. The American 11th Engineers were building a railway yard at Gouzeaucourt at the time of the German attack and, as they were unarmed, made a swift retreat until they could obtain weapons from the British and join the defence. Some made do with picks and shovels. Of the men captured, most managed to escape when the Guards counter-attacked.

The inability of the British to follow up their initial success was the result of excessive commitments elsewhere and the breakthrough plan had been too ambitious to begin with. The tanks had performed well, but their endurance was not great and many of them simply broke down. The tank losses totalled 179; of these seventy-one had broken down and forty-three had become stuck or had been ditched. British casualties were 44,207 of whom some 9,000 were taken prisoner. The Germans lost 41,000 of whom 11,000 were made prisoners. The Americans sustained eighteen casualties to add to the two that their unit had suffered on 5 September when two men became the first Americans wounded at the front.

What had been shown, despite the disappointing outcome, was that, subject to mechanical reliability, the tanks were capable of overrunning the strongest positions the Germans could create. Contact with the covering barrage had been lost, however, and the coordination of all arms of the fighting machine remained the weakest point of British tactics.

Lengthening the British Line

On 17 December 1917 General Pétain and Field Marshal Haig met and decided that, in accordance with the will of their political masters, the British would take over the front as far south as the river Oise by the end of January 1918. This meant taking over 25 miles (40 kilometres) of the former French line from St Quentin to a point halfway to Soissons at Barisis, south of the Oise; an increase of frontage of almost 30 per cent without a similar increase of manpower. Ten days earlier British GHQ had come to the conclusion that the Germans would launch an offensive in the west no later than March. At the same time the new British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, was resisting Haig’s demands for more troops. Given the awful toll of the Third Battle of Ypres there he was not without a reason, but the outcome was a shortage of men to defend the extended line; of the 38,225 officers and 607,403 men trained and ready in England, fewer than 200,000 were released. Nor could either the French or the English look to America to plug the gap. Although the first detachment of the American Expeditionary Force had landed, 14,000 strong, at St Nazaire the previous June and more had arrived since then, they were still not fully trained and ready to enter the line. On the other side the Germans and the Russians were now in negotiation to end the war on that front, so the prospect of German reinforcements arriving in the west was very real. The British reorganised, reducing the strength of a division from twelve battalions to nine, thus releasing 150 battalions for allocation to other units. The effect on morale and the destruction of established relationships was marked.

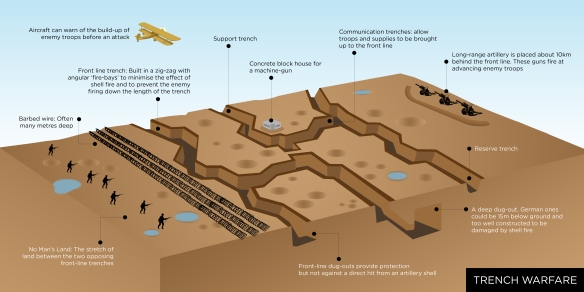

The British were now giving serious attention to defence. The new concept was defence in depth – a zone some 12 miles (19 kilometres) deep. The front line was to be lightly held, giving a Forward Zone of barbed wire and machine-gun nests covering the front trench and dominated just to the rear by redoubts, positions of all-round defence. Behind that was an area occupied by artillery that could be withdrawn if threatened with being overrun. Then came the Battle Zone, an area between 1 and 2 miles (1.5 to 3 kilometres) deep, peppered with machine-gun positions, in which an enemy would be shattered by artillery and cut down by machine-guns. The Rear Zone was, in effect, a second battle zone to be brought into use in the event of the first one being overcome. On paper it was all very fine. The problem was that it did not exist on the ground in January 1918, having only been formulated and propagated by GHQ on 14 December 1917.

The German Concept of Attack

Ludendorff had been planning an attack since the middle of 1917. He wrote in praise of his troops, but recognised that continual defence was not the way to seize victory, and it was vital to gain success before the full force of the Americans was brought to bear in Europe. He later wrote of the tactics and organisation in the infantry he had introduced:

The light machine-gun and the rifleman formed the infantry group, which hang together in trouble and danger and the life and death struggle. Its fire power was further increased by quick-firing weapons of all kinds and various sorts of rifle grenades.

To the heavy machine-gun, with its longer range and greater effect, fell the task of facilitating the approach of the groups to the enemy’s position by keeping the latter under fire. Of course, it had to accompany the advance of the infantry. Therefore, although itself ‘infantry’, it had already become a sort of ‘companion’ or auxiliary arm to the infantry.

The second auxiliary arm, of special use at short ranges against targets offering more than usual resistance, was the light trench mortar…

Of course massed artillery prepared the attack. It could, however, only do so in a general way, and left untouched too many of the enemy’s strong points, which had to be dealt with in detail at the shortest ranges. In each division, therefore, field guns were withdrawn from their units for short-range work, and were attached to battalions or regiments as infantry guns.

In addition, each division had a company of medium trench mortars which were also to be made as mobile as possible and allotted to battalions as required. Finally, there were the flame projectors, which could be brought into action at the shortest ranges against an enemy in blockhouses, dug-outs and cellars.

We had no tanks. They were merely an offensive weapon, and our attacks succeeded without them.

At a meeting in Mons on 11 November 1917 the German High Command entertained a range of attack plans and from these ‘Michael’, the attack at the southern end of the British line, between Arras and the French, was eventually selected to be the first of them. The tactics would be based on Captain Hermann Dreyer’s paper, The Attack in Positional Warfare, published on 26 January 1918, which summarised their most recent thinking. The approach was to use small, specialist units to penetrate the enemy line and bypass strong-points, allowing the follow-up troops to complete their envelopment and destruction. The leading units relied on light machine-guns and grenades, while the more conventional troops that followed brought with them mobile trench-mortars and horse-drawn field guns, as Ludendorff described in detail. Battalion organisation now generally consisted of four rifle companies with five light machine-guns and two light mortars, a machine-gun company with twelve Maxims, and a mortar platoon with four Minenwerfer. The way would be opened for them by a ‘fire-waltz’ as designed by Colonel Georg Bruchmüller. The components of the bombardment were a mix of shells – high explosive, smoke, tear-gas and poison gas – on front-line positions and suppressive artillery fire on enemy artillery.

To avoid ranging shots revealing German knowledge of British positions, a variant of the British method used before the Battle of Cambrai was developed for the artillery by Captain Erich Pulkowsky. The guns were characterised individually by test firing them well away from the line to determine the precise performance of each weapon. Each one could then, taking account of meteorological conditions, be targeted on a specific point identified on a map. Total surprise and comprehensive confusion of the defenders was the desired result. In addition registration of guns took place during the bombardment to range guns onto the targets they were given for later phases of the gunnery assault.

As the winter of 1917–18 softened to spring the race was on, with the British furiously constructing their defence and the Germans gathering for attack. The Somme had been comparatively quiet for almost a year while other fronts learnt lessons in warfare, bought in blood. The Somme was to be riven once again.