The Plain of Yarmuk lies about forty miles southeast of the Golan Heights. At the time, it was well watered and excellent for both grazing animal stock and maintaining an army for an extended period. It was fortunate for the Arabs that it was, as the Byzantines waited almost two months before advancing to attack the position. First, they tried to buy off the Arab invaders. When Khalid refused a final bribe offered by the Byzantine commander Vahan, the armies could no longer avoid battle. Some Christian sources state that the Byzantines were forced to attack as the caliph, Umar, was constantly sending reinforcements and the Byzantines feared they would soon find themselves outnumbered. Among these reinforcements were six thousand Yemenis, which included in their number one thousand elite Companions of the Prophet as well as one hundred veterans of the Battle of Badr—Islam’s first battle.

According to a description given by the historian A. I. Akram, the battlefield consisted of the Plain of Yarmuk, which was fenced in along its western and southern borders by deep ravines. Also along its western side was the yawning Wadi-ur-Raqqad, which joined the Yarmuk River near Yaqusa. This steep-banked, deep ravine ran for almost a dozen miles from northeast to southwest. Although troops could cross the ravine at several places, there was only one main crossing.

Battle began on August 15, 636. Nothing is known of the Byzantine dispositions. Some sources claim the bulk of their infantry was on the right flank, with the Armenians in the center and their Arab allies (mostly Ghassanids) on the right. Others claim that the infantry extended along the entire front, with the Ghassanid cavalry stretched out in front and other cavalry formations dispersed evenly among the infantry line. Even less is known about the Arab battle formation, except that Khalid kept an elite cavalry formation in reserve and close to his person. Akram relates that, believing his men would be reluctant to abandon their wives and children to Byzantine mercy, he ordered them to pitch camp directly behind the Arab battle formation. As the women arrayed themselves, Abu Ubaidah visited the various camps, giving instructions to the women: “ ‘Take tent poles in your hands and gather heaps of stones. If we win all is well. But if you see a Muslim running away from battle, strike him in the face with a tent pole, pelt him with stones …’ The women prepared accordingly.”

The first day opened with dueling champions. It appears that, by far, the Byzantines got the worst of these duels, and noon found their collection of champions much reduced. In fact, as many of these champions were senior commanders, their loss had a strong negative effect on Byzantine cohesion as the battle developed. To stop any further rot of Byzantine morale, Vahan ordered a large portion of his infantry to advance. The failure to rapidly replace commanders lost in the earlier duels probably accounts for the listlessness of this first attack. Although the fighting continued until sunset (at which time both sides separated for the night), it was not pressed home with any ferocity and casualties on both sides were minimal.

On the second day, the Byzantines attacked before dawn, hoping to strike while the Muslims were at morning prayers. They did manage to surprise the main Arab army, but a strong Arab outpost line slowed the advance and negated any Byzantine advantage. Although the Byzantines eventually overwhelmed the outpost line, the skirmishers held long enough for the Arab force to muster in battle formation and counterattack.

As the Byzantine center held the Arab center in place, successive heavy attacks, undertaken mostly by Slavs, hammered the Arab right. On the third Slavic charge, the Arab line broke. An Arab cavalry charge slowed the Byzantine pursuit just long enough to give the retreating Arabs time to reach their camp. Here they encountered something more fearsome than the Slavs—their own wives.

According to Akram, the women screamed curses in an attempt to shame the fleeing Arab force. When this failed to stem the Arab flight, the women assaulted them, as they had been instructed, with stones and tent poles. “This was more than the proud warriors could take. Indignant at their treatment, they turned back from the camp and advanced in blazing anger.”

The same scene played out on the opposite flank. But here, the seventy-three-year-old Abu Sufyan, a respected warrior and father of the founder of the Umayyad dynasty, was the first to retreat. He therefore was the first to encounter his wife, the formidable Hind. Hind was originally a strong opponent of Muhammad and was famous for supposedly eating the liver of Muhammad’s uncle after he was killed in battle. According to Akram, “She struck at the head of his horse with a tent pole and shouted: ‘Where to, O Son of Harb? Return to battle and show your courage so that you may be forgiven your sins against the Messenger of Allah.’ ” Abu Sufyan had experienced his wife’s violent temper before and hastily turned back. With the help of Khalid’s reserve cavalry, which attacked first on the right flank and then the left, the Arabs turned back the Byzantine tide. By the end of the second day, the toll in casualties had mounted, but no side had a clear advantage.

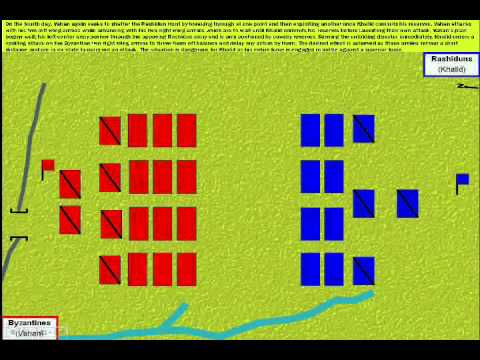

On the third day, Vahan decided to concentrate his assaults on the weakened Muslim right flank. To weight the attack, he reinforced his own left with Armenians from his center and right. As the assault began, the Byzantine center and right were expected to make enough of a demonstration to pin their opposite numbers and hopefully attract the attention of at least part of Khalid’s reserve. They failed at both tasks.

At first, the Byzantine main assault made good progress. But as the rest of the army stood almost idle, Khalid was able to use his reserve to strike at the exposed flank of the advancing Byzantines. At the same time, the Arab right-wing commander used his own cavalry to strike the other flank, threatening to trap over a third of the Byzantine force in a deadly double envelopment. The Byzantines retreated, suffering great loss without gaining much beyond forcing the Arab infantry to again suffer indignant insults from their wives. As one Muslim soldier exclaimed, “It is easier to face the Romans [Byzantines] than our women.”

The fourth day saw more hard fighting. Having witnessed Khalid commit his entire reserve against the Byzantine right flank the day before, Vahan planned to take advantage of a similar circumstance if one was offered or could be forced upon the Arabs. He once again sent his left flank against the seriously depleted Muslim right and waited for Khalid to commit his reserve. When he did, Vahan planned to order a general assault along his entire line.

Khalid had worried himself during the night about just such a stratagem. To counter it, he ordered his left flank and center to advance as soon as the Byzantine attack began. By doing so, he hoped to forestall a general Byzantine assault and to simultaneously force the Byzantine left flank away from the rest of the army so it could be enveloped and destroyed. As soon as the Byzantine assault on the Arab right flank opened, the Arab center and left went forward. When they came within range of the Byzantine archers, catastrophe struck. Hundreds of Muslims fell, and according to Akram, seven hundred Muslims lost at least one eye, including the aged Abu Sufyan. This calamity is still referred to in Arab lore as “the Day of the Lost Eyes.” Unable to stand up to the intense arrow storm, the Arabs retreated.

While the Arabs were still reeling, the Byzantine right and center advanced. Under unrelenting pressure, the Arab line broke and the Byzantines came on with renewed fury. The day was saved only by a cavalry regiment commanded by the fearless Ikrimah, who refused to retreat and had his four hundred men join him in a blood oath. Ikrimah’s cavalry struck hard at the advancing Byzantines and for a few moments halted their advance. But doing so came at great cost, as Ikrimah was killed and all four hundred of his regiment were seriously wounded or killed. Their sacrifice was not in vain. It bought time for the Arabs to form a ragged defensive line, which few thought could hold. For the Arabs, this was the crisis of the battle.

The women, who had been preparing to hurl insults at their retreating men, took up another plan when they saw the damaged Arab line turn and prepare to hold. They left the camp and went forward, armed with tent poles and swords. They pushed through the exhausted soldiers and took the first brunt of the Byzantine charge. As Akram tells the story: “The sight of their women fighting alongside, and some even ahead of them, turned the Muslims into raging demons. In blind fury they struck at the Romans [Byzantines] in an action in which there was now no maneuver and no generalship—only individual soldiers giving their superhuman best.” This furious assault struck the Byzantine advance just as it was exhausting itself. In an instant, victory was snatched away, as the Byzantines, who fell back slowly at first, soon routed.

On the other flank, the day had gone much like the day before. The fighting had been brutal, costly, and inconclusive. There was, however, one bright spot for the Arabs. The Christian Arab Ghassanids had become separated from the main army during the battle. Rather than try to rejoin it during the night, the Ghassanids deserted the battlefield, depriving the Byzantines of their best cavalry formations.

The next morning, Vahan sent an emissary to ask for a truce to last a few days so that fresh negotiations could begin. Khalid, realizing that the Byzantines’ offensive spirit was broken, had the emissary carry back his negative reply: “We are in a hurry to finish this business.” There was no action that day, allowing Khalid to rest his men and reorganize his cavalry for an offensive the next day. He ordered all of his cavalry regiments formed into a single striking mass of eight thousand warriors. The only cavalry he detached was five hundred men, sent on a wide circle around the Byzantine left flank. There they occupied the only escape route the Romans would have come morning.

The following day began with another clash of champions. This time a Byzantine general, Gargas, demanded to fight the Arab commander. Khalid prepared to take up the challenge when Abu Ubaidah insisted that as he had been given command of the army by the caliph, it was his duty to take up the challenge. The fight between the two men went on for some minutes before Ubaidah dropped his opponent with a thrust to the neck.

As soon as Ubaidah reentered Muslim lines, Khalid ordered a general assault all along the line. Once the Byzantines were pinned in place, he took his cavalry on a wide, sweeping move around their left flank. As the cavalry approached the battle, Khalid broke it into two parts. One part attacked the Byzantine cavalry to keep it out of the battle. The other smashed into the exposed left flank and rear of the Byzantine infantry line. The Slavs holding this sector of the line fought fiercely, but, attacked from three directions, they were soon reeling toward the center. Their retreat disordered the already hard-pressed center, which began to come apart. Vahan saw what was happening and tried to gather his cavalry into a large striking arm so as to counter the Arab charge. It was the right idea, but Khalid did not allow him the time to complete this concentration. Successive Arab cavalry charges broke the Byzantine cavalry before it could form properly. Vahan, despite his desire to continue the fight, was swept away with his own cavalry as it retreated to the northwest.

As the Byzantine cavalry deserted the field, the Byzantine infantry was left to its fate. Khalid immediately re-formed the Arab cavalry and struck directly into the rear of the infantry, which promptly broke and ran in the only direction that appeared open, toward the imposing Wadi-ur-Raqqad, a ravine that could be crossed only at a single point. When the fleeing men arrived at the crossing, they found it held strongly by the five hundred horsemen Khalid had sent out the night before. Unable to break through and pushed hard from the rear, the Byzantines were herded into a compact mass. From that point on, the battle descended into a slaughter. Akram describes the end: “The screams of the Romans mingled with the shouts of the Muslims as the last resistance collapsed, and the battle turned into a butchery and a nightmare of horrors.”

Khalid pursued the battered Byzantine remnants hard, catching up to them near Damascus. After a short fight, the Byzantine army was destroyed and Vahan killed. Khalid reoccupied Damascus without having to besiege it. As for Heraclius, he was enraged at news of the defeat. After consulting his advisers, he conceded that the loss was God’s punishment for the sins of the Byzantines and his own transgressions, which included his marriage to his niece. Without money or troops to continue the war, Heraclius took a ship from Antioch back to Constantinople. He was able to create a buffer zone in Anatolia, but the Arab conquests went on without pause for another century. Constantinople itself went through many ups and downs before its final fall to a besieging Muslim Ottoman army over eight hundred years later, in 1453.

It is one of the quirks of history that the Muslim invasions struck at what may have been the only time they had the slightest chance of success. If they had come a decade before, they would have faced the full might of the Sassanid and Byzantine Empires before they had exhausted themselves in battle against each other. If they had come a decade later, the Muslims would have encountered two empires well along the road to economic and military recovery. In either case, the Arab invaders would likely have been torn to pieces by either empire or both. As it was, the initial Arab invasions were a near run thing, and they could have gone either way. However, in the end the Muslims prevailed and the Byzantines no longer had the wherewithal to create another field army. As a result, all of Syria and Palestine fell to the Arabs. This was merely the beginning of a century of Arab conquests that ended only when Charles Martel defeated an Arab invasion force at Tours in central France in 732. By that time, the Arabs controlled all of the southern Mediterranean, including most of Spain, and were pushing deep into India in the east.

It is one of the great what-ifs of history to ask what would have become of the Islamic faith if the Byzantines had won at Yarmuk. At the very least, they would have repelled the Islamic tide early, and the Arab-Islamic civilization that now dominates from the Bosporus to the Strait of Gibraltar would not exist. The entire Mediterranean would have remained culturally Greco-Roman and Christian, and if it survived at all, Islam itself would arguably have been relegated to the deserts of Arabia.