The Islamic Conquest Begins

In 629, the Prophet Muhammad, taking advantage of a truce between himself and his mortal enemies, the quraysh tribe, took the time to send a series of ultimatums to the kings of persia, yemen, and ethiopia and the byzantine emperor heraclius. To Heraclius he wrote:

Peace be upon him, he who follows the right path. Furthermore I invite thee to Islam; become a Muslim and thou shalt be safe, and God will double thy reward, and if thou reject this invitation, thou shalt bear the sins of persecuting Arians.

It is uncertain if Heraclius ever saw this ultimatum from an unknown desert upstart. But even if he had, it was unlikely to have made much of an impression on him. Desert raiders had plagued the Roman Empire since its founding. They remained a thorn in the side of the empire even after the Western Roman Empire collapsed and imperial power recentered itself on Byzantium. For Heraclius it was just one of many thorns, and far from the most dangerous he had encountered in the almost twenty years he had been on the throne.

Heraclius had seized the Byzantine throne just as the empire’s fortunes approached a low ebb. The death of Justinian the Great in A.D. 565 left a leadership void that nearly destroyed all he had built. Faced with an empty treasury, his nephew and successor, Justin II, ended a tried-and-true Roman practice of buying off enemies that one was temporarily too weak to fight, leaving much of the empire open to invasion and ruin. Sensing weakness looming, barbarian tribes once again descended on the empire. The Lombards, who had been contained in the Balkans, immediately moved into northern Italy. Within a few years, they controlled almost the entire peninsula, wiping out territorial holdings that had taken Justinian’s armies a generation to gain. The fierce Avars stayed in the Balkans, where they undertook a campaign of conquest that eventually led them to the walls of Constantinople. In 572, Justin’s inept diplomacy, coupled with a refusal to pay tribute, led to a renewed war with Persia, a war Byzantium was ill prepared to fight. Justin’s defeat in two campaigns cost the empire much of Mesopotamia and the fabulously rich province of Syria. It also cost Justin his sanity, and special rails had to be placed in the palace windows to keep the emperor from jumping out.

After the death of Justin in 578, his picked successor, Tiberius, rose to the throne. He managed to stop the Persian advance but then repeated the great Justinian’s mistake of denuding the empire of troops, sending them off to regain distant portions of the lost Western Empire. For a while, Byzantine troops were able to reverse Lombard gains in Italy, but only at a high cost in treasure and the blood of veteran troops Byzantium could ill afford to lose. With the bulk of the Byzantine army either fighting in the west or guarding the Persian frontier, the Avars took the opportunity to continue stripping away the empire’s Balkan provinces. Tiberius died, or more probably was murdered, in 582. He was succeeded by a Byzantine general, Maurice, who was having some success in a new round of fighting with Persia.

Upon his accession to the throne, Maurice launched a triumphal campaign against Persia. Taking advantage of political turmoil there, he decided to send an army to help the deposed Sassanid Persian ruler, Khosrau II, regain his throne. A combined Byzantine-Persian army defeated the usurpers at the Battle of Blarathon, restoring Khosrau to power and bringing an end to the Persian wars. To seal a lasting peace, Maurice married off his daughter Mariam to Khosrau. A grateful son-in-law not only returned all of Byzantium’s lost territory, he also ceded Armenia to the empire.

In 591, with the Persian frontier secure, Maurice turned on the Avars with a vengeance. The Avars, who had been plundering the Balkans for over a decade and for a time even threatened the capital, had grown complacent. They were completely unprepared for the scale and ferocity of the Byzantine assault and were defeated south of the Danube. In 593, Byzantine troops advanced across the Danube into Wallachia. There, the Avars and their Gepid allies were roughly handled in their own homeland and sued for peace in 595. However, this peace was short-lived, and by 599 Byzantium and the Avars were again at war. In 602, the Avars suffered another crushing defeat in Wallachia, allowing the Byzantines to once again form their frontier defenses along the Danube. Behind these defenses, Maurice hoped to repopulate the devastated Balkans with an influx of Armenian settlers.

For a moment, it seemed that Byzantium had weathered the great storm and could focus on rebuilding. However, Maurice’s treasury was empty, and in order to conserve money he made a number of unwise choices. First, he decided not to pay any ransom for the twelve thousand soldiers the Avars had captured during the years of war. The barbarian Avars, seeing no hope of profit, promptly slaughtered the captives rather than feed them through another long winter. Maurice’s callous disregard for the lives of his soldiers unsettled his army. They selected one of their number, Phocas, to lead a delegation to Byzantium to place their grievances before the emperor. Maurice rejected these complaints and forced Phocas to endure the further insult of being publicly slapped about by court officials.

Phocas bore his humiliation silently and returned to the army to nurse his pride. Not long afterward, he and the rest of the army learned that Maurice, in another cost-cutting measure, had ordered their pay cut by a quarter. Thus, the army that Maurice ordered on a major punitive expedition across the Danube in 602 was seriously disgruntled. Despite the soldiers’ anger, the campaign was successful, and the army was heading back across the Danube to occupy well-prepared and warm winter quarters when they were ordered to spend the winter on the far side of the river. Without prepared forts the army would not only freeze, it would be exposed to their enemies without any significant protection. At that point, the army, led by Phocas, understandably mutinied and crossed the Danube to march on Constantinople. Maurice fled to a nearby monastery.

Upon entering the city, Phocas was crowned emperor. His first act was to have Maurice dragged from the monastery and forced to witness the beheading of his six sons before his own execution. Well aware of the need to solidify his hold on power, Phocas played the part of populist. He immediately lowered taxes, for which his popularity with the masses soared—for a time, although that did little to help fill his empty treasury. Furthermore, all was not well outside the capital. King Khosrau, who had owed his Persian crown to his father-in-law, Maurice, took advantage of his benefactor’s death to break the peace treaty and renew the Byzantine-Persian wars. Worse, the commander of the Byzantine army on the Persian frontier, Narses, remained loyal to Maurice and led his army into revolt. To deal with Narses, Phocas had to denude the Balkans of every available soldier.

Taking advantage of the Byzantine army’s withdrawal, in 605 the Avars crossed the Danube in force. Before them lay the defenseless Balkan provinces for the taking. Meanwhile, the Persians marched from the east, ostensibly to save Narses, who was besieged in Edessa. So began a grinding war of attrition that lasted for twenty years. Moreover, in 608 the Byzantine commander in Africa, Heraclius the Elder, and his son, also named Heraclius, raised the banner of revolt. This caused rioting in many of the cities of Syria, which Phocas crushed with such severity that the region’s enmity to Constantinople was reportedly still palpable centuries later. Of course, Byzantium’s enemies took advantage of the civil war to renew their advances. The Persians took much of Anatolia, while at the same time Avar and Slav raiding parties were again daring to approach the northern walls of the capital.

It was at this low ebb in Byzantine fortunes that Heraclius the Younger entered the capital with a small force. The imperial guard, commanded by Phocas’s son-in-law Priscus, threw in their lot with the new usurper. Phocas was brought before Heraclius, who became enraged by Phocas’s answers to his questions, drew his sword, and beheaded Phocas on the spot. Heraclius’s first attempts to restore the military situation failed, and Byzantium’s enemies continued to advance. By 611, Persian campfires were visible from Constantinople’s battlements. With no army and no money to raise a new one, Heraclius saw things go from bad to worse. First Antioch fell to the Persians in 611, followed by the collapse of Damascus two years later, and finally Jerusalem in 614. The loss of Jerusalem also meant the loss of “the True Cross,” the most sacred relic in Christendom, which was taken to Ctesiphon, the Persian capital. In 617, Persian forces overran Egypt, thus stripping Constantinople of the province that supplied its food and a large portion of its tax revenues.

Heraclius remained behind Constantinople’s impregnable walls, biding his time and preparing a great counterattack. By once again emptying the treasury, he was able to buy peace with the Persians, although when his cash on hand alone proved insufficient, he also promised the delivery of one thousand virgins. Through other inducements, Heraclius managed to achieve a temporary truce with the Avars in 619. This general peace bought the emperor time to reorganize the army and through extraordinary means, including melting down church treasures, raise a war chest. By 622, all was ready for Byzantium to take the offensive and regain its lost territory. Over the next five years, in a series of brilliant campaigns, Heraclius defeated the Persian armies and stood outside the gates of Ctesiphon. Khosrau’s subjects believed that his defeats indicated the disfavor of the gods, and his son, Kavadh II, seized the throne, whereupon he immediately sued for peace. As a result, Persia withdrew from all occupied territories and returned the True Cross. After a triumphal march through the retaken provinces in 629, Heraclius returned the relic to Jerusalem.

Muhammad sent out his ultimatums soon afterward. These came at a time when the Byzantine Empire required rest above all else. The protracted wars had not only wrecked Persian power, but had exhausted Byzantium and devastated its richest provinces in Anatolia, Syria, and Palestine, all of which required many years to recover. And even though Persia lay prostrate, the Avars and Slavs still dominated the Balkans, depriving the empire’s coffers of revenue. It would take a supreme effort for the empire to muster sufficient forces to fend off another invader. Moreover, any defeat would be catastrophic, as there were no reserves, either of treasure or of manpower.

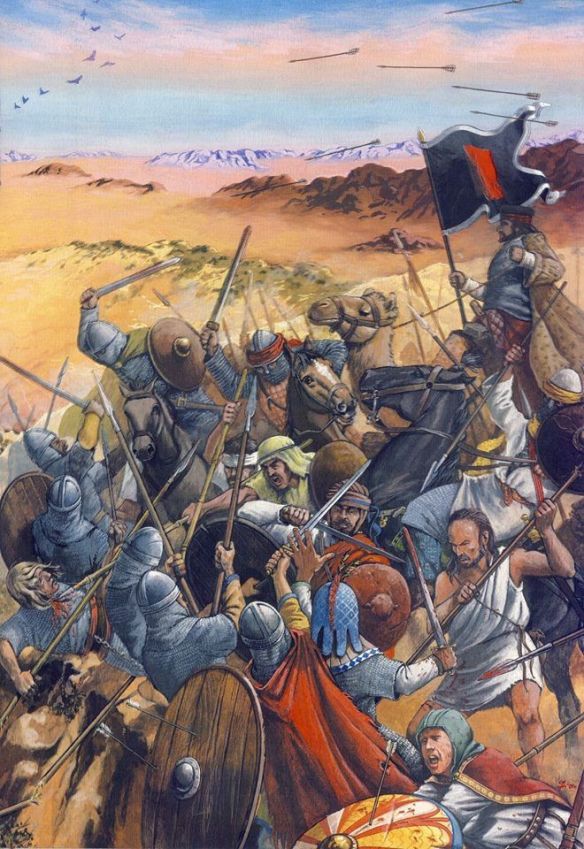

This new threat facing the Byzantine Empire was unlike any that had come before it. The Byzantines had always had to deal with raiders coming out of the sands of Arabia, but what was about to break forth from the desert was much more than a pinprick raid by a rogue tribe set on gathering a bit of plunder before vanishing back into the wastelands. Rather, all of the desert tribes were now unified under the single banner of Islam, a highly expansionist faith that gloried in spreading its new creed through conquest.

When Muhammad died in 632, his unification of the Arab tribes remained unfinished. That job was completed by his successor, Abu Bakr, who quickly subdued apostatic tribes in the the Ridda Wars. When they were over in 633, Abu Bakr possessed a unified veteran army and a superb commander to lead it, Khalid ibn Walid, “the Sword of God.” After securing his own position, Bakr sent eighteen thousand picked men, commanded by Khalid, into the Persian province of lower Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) in 633. The exhausted Persians put up the best opposition of which they were still capable, but by the end of the year most of the province was in Arab hands and the Persian capital was in danger. The final destruction of Persia’s Sassanid dynasty was averted when Khalid received an urgent message to take his army to the aid of another Muslim invading force that Bakr had sent into Palestine.

The prelude to the Battle of Yarmuk begins with Khalid’s arrival in Syria, where he immediately began raiding throughout the province. By this time, Heraclius learned of Arab victories over the Persians and realized he faced a much greater threat than mere raiding parties. He ordered his brother Theodore to assemble an army at Ajnadayn and prepare to meet the Arab army in the field. It took the Byzantines two months to concentrate local forces, a feat the fast-moving Arabs accomplished in a week. The Battle of Ajnadayn was long and hard-fought. Despite heavy losses on both sides, the Arabs held the field at the end of the day, as the Byzantine army scattered in three directions. In the aftermath of the battle, Khalid’s warriors conquered most of Syria and Palestine, including the great city of Damascus. For his part, Heraclius ordered his brother arrested and had the reorganizing army retreat from the exposed city of Emesa to Antioch. Understanding that confronting the Arab threat was beyond local resources, Heraclius began assembling the imperial army for action.

In 637, the Byzantine army began to move. This army was a polyglot force of mercenary Slavs, Franks, Geogians, Armenians, and Christian Arabs (Ghassan tribe). This force was organized into five divisions each with its own commander and with Theodore Trithourios (not to be confused with the emperor’s brother Theodore) in overall command, while Vahan, an Armenian, was expected to take command in the event of battle. Language barriers added to the problems of this impractical command structure, which was made worse by the simple fact that many of the commanders of the Byzantine divisions neither liked nor trusted one another.

There were also major command changes on the Arab side. By this time, Abu Bakr was dead, and the new caliph, Umar, promptly relieved Khalid and ordered Abu Ubaidah to assume command of the Arab armies in Palestine and Syria. Abu Ubaidah was a pious man and politically reliable, but although courageous, he was not on the same level as Khalid as a general. Remarkably, he was well aware of his own shortcomings and as Khalid remained with the army, Abu Ubaidah deferred to him in most military matters.

After the Battle of Ajnadayn, the Byzantine commanders were reluctant to face the Arabs in a major set-piece battle. Therefore, they began their advance hoping to surprise the Arabs and defeat each of their scattered forces before they could concentrate. Unfortunately, the Arabs had been watching the Byzantine buildup with some apprehension. Khalid advised Abu Ubaidah to abandon their gains, including Damascus, and concentrate the army farther south, nearer the friendly desert in case of a military reverse. As a result, the Arab army withdrew just before the Byzantines struck and began concentrating at Jibaya. Thus, the first and most powerful thrust of the Byzantine invasion struck open air.

Either because they were forced out by raiding Ghassanid Arabs (Christian Arabs in alliance with Byzantium) or because Khalid believed the ground near Yarmuk was a stronger defensive position, the Arabs retreated farther south and waited.