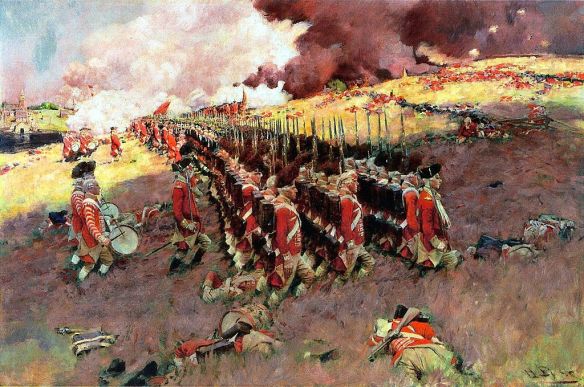

The Battle of Bunker Hill, by Howard Pyle, 1897.

Americans at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

In 1774 Liutenant General Thomas Gage was the most powerful man in America, and gunpowder was the focus of his urgent attention. Faced with radicals fomenting rebellion, the supreme military commander in North America and Royal Governor of Massachusetts followed the instincts of a sea captain beset by murmurs of mutiny—first, secure your powder. Gunpowder had become the principal means of making war and the volatile fuel of social unrest.

Since the colonies had almost no gunpowder mills, control of this strategic commodity seemed a sure guarantee of peace. A good portion of the supply in Massachusetts was stored in the Provincial Powder House built on a remote hill six miles north of Boston. To seize the powder, Gage needed to act quickly. If rebels got wind of his plan they could very well oppose the move or spirit the powder away in advance.

Gage’s experiences with gunpowder violence had been bitter ones. In 1745 he had served in the British force defeated at Fontenoy. His luck did not improve when, assigned to America, he accompanied the blunt and imperious General Edward Braddock on his 1755 campaign to drive the French from the Ohio Valley. Set upon by a force of Indians and Canadian militia, the redcoats were decimated. Gage’s rear guard allowed the escape of survivors, including a provincial officer named George Washington.

Conservative, devoted to the rule of law, the hard-working Gage was out of his element dealing with the quick-witted radicals who were egging on the Boston rabble. “Too honest,” one observer called him, “to deal with men who from their cradles had been educated in the wily arts of chicane.”

Honest or lacking imagination, Gage in 1770 had sent the notorious 29th Regiment of Foot into Boston to quell a disorder, leading to the spasm of musket fire and five deaths that the colonials called a massacre. He had recommended the punishing Coercive Acts in response to the dumping of tea into Boston Harbor in 1773, closing the port and curtailing the town meetings that bred the vice of “democracy.” Yet Gage remained cautious. Married to an American heiress and keenly aware of the risks of open conflict, he sought above all to avoid war.

At 4:30 on the morning of September 1, 1774, Gage sent a company of soldiers rowing across Boston Harbor in longboats. They marched to the powder house, a windowless stone tower, and removed 250 barrels of gunpowder, along with two brass field guns, securing them in the main British stronghold on Castle Island. The reaction to this operation confirmed for Gage the wisdom of his caution. Rumors tore through the land: Boston had been bombarded, six were dead, war was imminent. Patriots lit beacon fires and tolled church bells for hours. By the following day the country was teeming with armed patriots. Twenty thousand men from the Connecticut Valley alone took to the roads. Whig leaders struggled to restrain enraged citizens. Notorious Tories fled for their lives. It was a frenzy that would become known in New England as the Powder Alarm.

Gage abandoned as too provocative a plan to send troops forty miles inland to confiscate the store of powder from Worcester. Instead, he forced all Boston merchants to sell their stocks of gunpowder to the Crown. He set up cannon and fortifications on Roxbury neck, which connected Boston to the mainland. He urged his London superiors to assign him 20,000 more men. Considering that Britain’s peacetime army consisted of only 12,000 infantrymen, the request gave a hint of Gage’s uneasiness. The high command sent him 400 marines.

For their part, the rebels established a committee of “mechanics” to keep an eye on British movements with the hope of forestalling any more powder raids. The thirty Boston volunteers included the silversmith Paul Revere. “The spirit of Liberty was never higher than at present,” the 40-year-old Revere had written on September 4. “The troops have the horrors.”

In October, King George himself issued an order banning the import of gunpowder to America and decreeing that all supplies be secured for the Crown. Again the alarm went out. That December, Paul Revere rode fifty miles in a raging snowstorm to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to report that the British regulars were coming there to confiscate the gunpowder at Fort William and Mary.

Before the British reserves arrived, four hundred local militiamen marched on the fort. The outnumbered garrison managed to fire three cannon shots, hitting no one, before being overwhelmed. The rebels had the effrontery to haul down the king’s colors before breaking into the magazine and removing the powder. One hundred barrels of explosive were hauled out by cart and boat.

Gage watched events reeling out of control. At Newport, Providence, and New London, rebels removed gunpowder from depots and hauled it to the safety of the interior. In February 1775, Gage heard that ships’ cannon were being converted to field pieces in Salem. The force he sent to investigate found themselves eyeball to eyeball with a cadre of Salem militia and Marblehead fishermen. The troops backed down. “Things now every day begin to grow more and more serious,” wrote Hugh Percy, Gage’s loyal subordinate.

The king himself was livid over the theft of his powder and desecration of his fort. London urged action against the patriots, “a rude Rabble without plan, without concert, and without conduct.” The British commander was still convinced that the control of gunpowder was the key to defusing the threat. But any further operation to put the volatile substance under lock had to succeed—another fiasco like Portsmouth or Salem would be disastrous.

For his target, Gage selected Concord, fifteen miles northwest of Boston. The town was a center of rebel sentiment and supplies. One building, his spies reported, held seven tons of gunpowder. Gage had to strike at the rebels before they could muster their forces, which vastly outnumbered the troops under his command. The secret operation began at 10 P.M. on the night of April 18. British troops in Boston were awakened with a whisper and told to bring 36 cartridges of powder and ball. They slipped out the back doors of their barracks and made their way through the quiet streets. A dog barked—a soldier silenced the animal with his bayonet. Sailors ferried the 900 men across the Charles River. At two in the morning, wet and shaking with cold, the regulars began their march.

They had not been quiet enough. They began to hear, off in the distance, the ominous sound of clanging church bells and the crack of warning shots. Revere and his fellows had caught wind of the movement, crossed the river before the British, and were even now spreading the alarm through the countryside.

Gage had put two veterans in charge of the raid: the corpulent and careful Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, and the experienced Marine Major John Pitcairn. Pitcairn had a professional’s disdain for the noisy rabble. “If I draw my sword but half out of my scabbard, the whole banditti of Massachusetts will run away,” he wrote in a letter. “I am satisfied they will never attack regular troops.” Sensing the unrest spreading through the countryside, Smith sent Pitcairn ahead with six companies of light infantry. At 4:30, with the first gray light seeping into the sky, Pitcairn ordered his men to load their muskets. They bit off cartridges, poured in powder, rammed the balls home. They were about to march into the village of Lexington.

When they reached the triangular common in the center of the hamlet, they came face to face with a small group of the Middlesex County militiamen. The redcoats broke out of their column and formed a line. Bystanders poured from nearby Buckman tavern. Other townspeople watched from the surrounding roadways, only vaguely aware that they were witnessing an event of historic moment.

The two sides eyed each other across sixty yards of patchy grass. The soldiers were unlettered, hard-drinking men far from home, low in spirits, despised by the colonials around them. They likewise scorned the men opposite as “rebels,” “provincials,” “Yankeys.” Those militiamen, long hair tied back in queues, were hardly dreamy idealists. Many had lived through bloody encounters with Indians and French troops in the wilderness. Yet in spite of the mutual contempt, those on both sides of the green were, up to that moment, fellow countrymen, members of the British nation.

Some militiamen thought it foolhardy to stand in the way of the regulars. Their commander, Captain John Parker, silenced debate. “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon. But if they want to have a war let it begin here.” His men stood. The situation grew tense. The British soldiers began their distinctive battle chant, a menacing “Huzzah! huzzah! huzzah!” British officers screamed at the rebels to lay down their arms. Parker had second thoughts. With confusion mounting, he ordered the militia to disperse. Some did, “though not so speedily as they might have done,” one witness reported. Some stayed where they were.

Who fired the first shot that morning will never be known. The apprehension and animosity that had been growing for ten years suddenly came to a head. A shot, maybe two, rang out. The British infantry, though renowned for their discipline, began firing sporadically without orders. Some of the militia returned fire. Then came the awful, ripping sound of a full volley of musketry. Almost instantly, one witness reported, “the smoke prevented our seeing anything but the heads of some of their horses.”

Chaos descended on the green. The British regulars began to reload and fire with the speed conveyed by years of relentless drill. Horses bolted. Men ran and were shot down. Spectators fled in panic. One patriot, chased into the village meeting house, which served as an armory, thrust his firearm into a barrel of gunpowder, ready to blow the building up if the redcoats pursued. Jonathan Harrington, who lived in the village, fell with a ghastly wound to his chest. He crawled toward his home and died on his doorstep in front of his wife and son.

British officers ordered the drummers to beat the men to arms. Reacting automatically to the signal, the troops reassembled. They marched on, leaving eight dead militiamen behind them. They found no gunpowder in Concord—Revere’s warnings had allowed the patriots time to haul most munitions out of the village. After knocking the trunnions off several cannon and cutting down the town’s liberty pole, the regulars formed up for the long march back to Boston.

The clash that took place along that route has been enshrined in American mythology as an example of individualistic Indian fighting. Longfellow described “How the farmers gave them ball for ball/From behind each fence and farmyard wall.” Isolated skirmishers and ambushes played a role in the action, but most of the battle involved attempts by the American militia to stand up to the redcoats in conventional formations.

The events of the day were far worse than anything General Gage could have imagined in all his anxiety over gunpowder. His best troops had been smartly manhandled by a band of determined farmers and merchants. “The Rebels,” he wrote, “are not the despicable rabble too many have supposed them to be.”

Gage’s bad luck continued. He found himself besieged in Boston. By August, his own officers were refusing to obey him. He was recalled to England in October. By that time, a full-scale war had begun in North America.

In June, Gage assigned the duty of making the first serious strike against the rebels to the man who would replace him, General William Howe. The Americans had suddenly fortified Breed’s Hill on the Charlestown peninsula across the harbor from Boston. Military custom, an inflated sense of honor, and more than a trace of overconfidence all dictated a frontal assault on the ragtag rebel troops.

Dressed in their red woolen coats on a warm, sky-blue spring day, the British infantrymen struggled up the slope. One of the rebel commanders, Colonel William Prescott, was painfully aware that his men lacked gunpowder for more than a few volleys. His advice, “Don’t fire till you see the whites of their eyes,” became an adage for the history books, though similar words had been attributed to a Scottish lieutenant colonel in 1743. The sentiment was pure economy. The Americans waited, holding off their volley until the British regulars came within ten yards of their hastily built fortifications. The sudden crash of fire directly into their faces sent the British regulars reeling. They retreated to the bottom of the hill.

Howe and his officers, shaped by the conventions of European warfare, felt that to call off the assault or switch their direction of attack would be a stain on British honor. They ordered their men back up the steep hill. Again, disciplined American fire repulsed them. Nothing would do but a third frontal charge.

This time, no volley met the redcoats’ advance. The Americans had run out of gunpowder. Lacking bayonets, they were overrun and forced to retreat. The battle had been costly for the British. Of the 2,200 soldiers who had advanced, half had been killed or wounded. “A dear bought victory,” a British officer noted, “another such would have ruined us.”

The Americans’ failure to hold their position in the battle named for nearby Bunker Hill was a result of tactical ineptness and logistical oversight. But the incident was a reminder of a critical weakness in the rebels’ plan to take a stand against the King’s troops: They desperately lacked gunpowder.

Powder making was not unknown in America. During the French and Indian War of the 1750s, entrepreneurs had established a few small mills. But when peace returned, the government in London discouraged the trade, along with colonial manufacture in general. Royal governors instead imposed a tax on ships putting in at American harbors and earmarked the money to buy gunpowder made in England. In any case, the local product could not have competed with the powder ground in large English mills using the best Indian saltpeter.

As the nascent continental army settled in to a siege of British forces in Boston, the whole enterprise rested on a shaky foundation. In August 1775 George Washington wrote from Cambridge, “Our situation in the article of powder is much more alarming than I had the most distant idea of. We have but 32 barrels.”

This was enough to issue each man only about half a pound of powder. By the end of the month the supply had dwindled further. Firing powder-hungry artillery was almost out of the question. Looking on Boston from Prospect Hill, General Nathaniel Greene lamented, “Oh, that we had plenty of powder; I would then hope to see something done here for the honour of America.”

In the early stages of the war, the American forces had to beg, borrow, and steal gunpowder. An inventory of all thirteen colonies found only about 40 tons on hand, enough for a few months of operations. About half was sent to Cambridge to supply Washington’s army, the rest allocated for local defense. In June 1775 a hundred pounds of gunpowder could not be purchased in New York City at any price. A band of “Liberty Boys” in Savannah, Georgia, made off with a few barrels of powder from the government magazine in May, and returned in July to capture fully six tons of the precious explosive from a ship in the harbor.