Although an attack on Baltimore had been under discussion since the beginning of Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane’s Chesapeake Bay campaign (April–September 1814), Cochrane waited for nearly two weeks after the burning of Washington (24–25 August) before committing to the expedition.

The British were unaware that their reception at Baltimore would differ greatly from what they had seen at their capture and occupation of Hampton, Virginia (25–26 June 1813); at Washington; or at Alexandria, Virginia, during Captain James Gordon’s raid on the Potomac River (17 August–6 September 1814). From the spring of 1813, Major General Samuel Smith of the Maryland Militia had been in command of preparations with the full support of the city, state, and federal governments.

The city lay at the base of the harbor, which was on the Northwest Branch of the Patapsco. The entrance to this narrow inlet was blocked by a boom, sunken hulks, and up to 11 barges (two guns each) of Captain Joshua Barney’s flotilla with about 350 USN personnel. On the west point of the entrance stood Fort McHenry, which held 36 French 42-pdr long guns (lg) and a garrison of nearly 1,000 men (Corps of Artillery; Twelfth, Thirty-sixth, and Thirty-eighth U.S. Regiments of Infantry; Maryland Militia; and some Sea Fencibles) under Lieutenant Colonel George Armistead, while to the east was the Lazaretto Battery with three guns manned by men from Barney’s flotilla. To prevent a landing west of Fort McHenry via the Ferry Branch (the south branch of the river), there was Fort Babcock (six 18-pdr lg), Fort Covington (up to 10 heavy guns), and Fort Lookout (seven guns) and one more small battery. The first three were held by seamen from Barney’s flotilla and the USS Guerriere, and some Virginia Militia held the fourth. Just before the arrival of the British, the command of this part of the city, except for the naval parties, was given to Brigadier General William Winder, who was greatly dissatisfied with having to serve under Smith; Commodore John Rodgers commanded all naval detachments.

In the days immediately before the British arrived, a massive military and civilian force (including a proportion of slave labor) had fortified Hempstead Hill on the city’s east side. This consisted of nearly a mile and a half of trenches on the ridge joining eight batteries, which held 62 guns. These were manned by seamen and U.S. Marines from the Guerriere and a regiment of Maryland Militia artillery. Infantry support came from elements of two brigades of Maryland Militia, a battalion of Pennsylvania Militia, and some U.S. Marines. Tentative plans had even been made to fortify buildings in the city if necessary.

General Smith used Baltimore’s “City Brigade,” the Third Maryland Brigade (about 3,200 men in five regiments of infantry and smaller units of cavalry, rifles, and artillery), as his advance. On 11 September, Brigadier General John Stricker, its commander, took up a position about four miles east of Hempstead Hill at a narrow point on Patapsco Neck. He placed his infantry here and sent part of his cavalry and rifles forward to watch the British.

After arriving at the Patapsco River on 10 September with a fleet of about 50 warships, the British began landing about 4:00 A.M. on 12 September at North Point, near the tip of Patapsco Neck. Led by Major General Robert Ross, with Rear Admiral George Cockburn in attendance, the 1/85th Regiment of Foot and the light companies of the 1/4th, 1/21st, and 1/44th Regiments of Foot followed in time by the rest of these latter units and detachments of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and the Royal Sappers and Miners; they totaled about 2,500 men. About 1,350 men also landed from the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Royal Marines, the Royal Marine Artillery (and presumably men of the Rocket Corps and the Rocket Troop) and RN officers and seamen. To provide a diversion to the land force, Cochrane sent some of the smaller warships up the river toward Baltimore.

While the landing was still under way, Ross advanced westward with the light infantry around 8:00 A.M., covering about four miles before halting; the heat and humidity were oppressive and took its toll on the troops. About 10:00, the column advanced, and shortly thereafter the opposing light infantry began skirmishing. About 2:00 P.M., with a guard of about 50 men, Ross and Cockburn rode up to inspect the action, and Ross was hit by a rifle bullet and soon died. Command now devolved on Colonel Arthur Brooke (44th Foot), who hurried to the scene and pushed the column forward where it engaged more infantry and artillery sent forward by Stricker.

Stricker succeeded in enticing the British to his position. With one of his units in reserve, he formed a line of his entire force behind a fence just inside Godley Wood, spanning the width of Patapsco Neck. Before them lay an old field about 500 yards wide, and here Brooke arrived and deployed his skirmishers and main line under American artillery fire, which he returned with guns and rockets. Brooke sent the 4th Foot to flank Stricker’s left, for which Stricker made adjustments. With part of the remaining units in line and some behind, waiting to deploy as they reached the field, Brooke ordered a slow advance about 3:50.

Stricker’s left had difficulty deploying, and under their first fire a portion of the units broke and ran. The rest of the line delivered volleys and independent fire, but Brooke ordered a quickened advance, and as the British rushed forward, Stricker’s line withered and broke. Brooke declared that the action, which became known as the battle of North Point (or the battle of Godley Wood among some authorities), lasted about 15 minutes. Some of the British referred to it as a second “Bladensburg Races.” It had been a bloody affair, however; the British reported 38 dead, 251 wounded, and 50 missing, while Stricker claimed 24 dead, 139 wounded, and 50 captured.

Stricker was able to congregate his units and withdraw toward Hampstead Hill, where Smith positioned him to the left, and outside, of the fortifications; Smith also ordered Winder to this place with part of his brigade of regulars and militia. Brooke camped on the battlefield, where his men suffered without cover during a night of rain.

On 13 September, Brooke advanced and came within sight of Hampstead Hill around 11:00 A.M. He was surprised at the strength of the American position and soon heard rumors that 20,000 men stood ready to repel him.

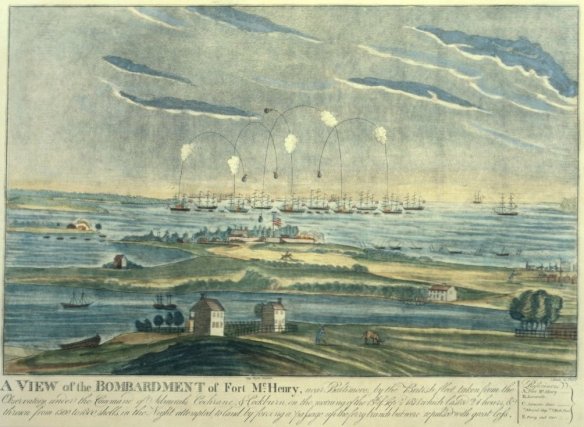

Meanwhile, the famous naval bombardment of Fort McHenry had begun that morning around 8:00. Sixteen of Cochrane’s shallower draft warships were within five miles of the city by late on 12 September. By the next morning, five bomb vessels and the rocket ship Erebus moved to within two miles of Fort McHenry and opened fire. The Americans returned this, and Cochrane pulled his vessels back just out of range and resumed a tremendous bombardment with mortars, guns, and rockets that lasted until early the next morning. It is said the British fired between 1,500 and 1,800 rounds of mortars alone and that 400 of them fell on Fort McHenry, although surprisingly few casualties were reported. It was during this remarkably explosive display that Francis Scott Key formed the idea for his famous “Star Spangled Banner.” Around 3:00 A.M. on 14 September, Cochrane ordered a 1,200-man boat assault on the shore west of McHenry, but this never made shore because of the fire of the auxiliary forts.

While the bombardment was going on, Brooke was retreating. Cochrane had sent Cockburn a note questioning the value of attacking Hampstead Hill. Cockburn showed it to Brooke, who called a council of war from which Cockburn excused himself, not wanting, presumably, to “encourage” Brooke into action as it was suggested he had done with Ross during the march to Washington. After exchanging prisoners and wounded with the Americans, the British marched back to North Point and were all embarked by mid-afternoon on 15 September.

The defense of Baltimore was unprecedented. It reestablished American confidence and was used as a bargaining chip in peace negotiations. The attack was a black eye for Cochrane and the military, although Brooke’s decision to withdraw in the face of such formidable fortifications was probably the right one.