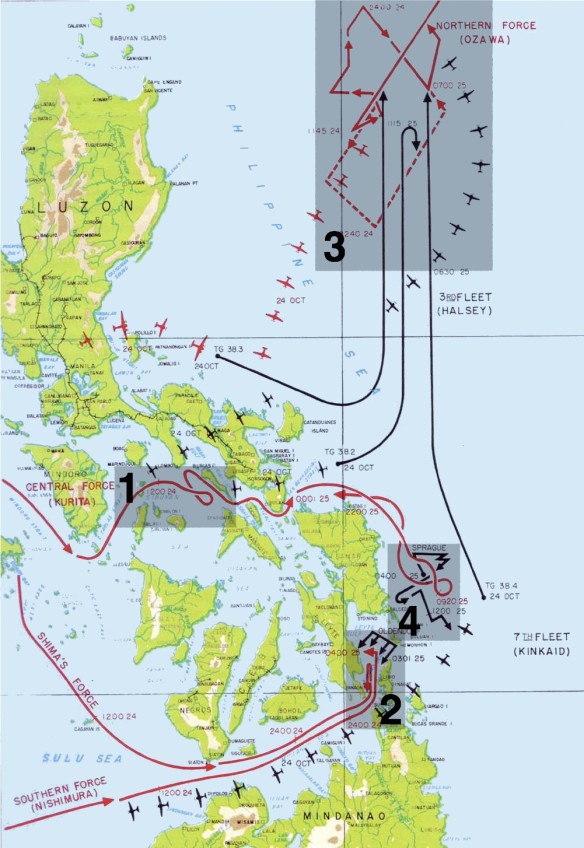

The four main actions in the battle of Leyte Gulf: 1 Battle of the Sibuyan Sea 2 Battle of Surigao Strait 3 Battle of (or ‘off’) Cape Engaño 4 Battle off Samar. Leyte Gulf is north of 2 and west of 4. The island of Leyte is west of the gulf.

At about the same time that Halsey’s seventh installment appeared, Bernard Brodie published in the Virginia Quarterly Review an article entitled, “The Battle for Leyte Gulf.” Although Brodie gave Halsey his due by recognizing the admiral’s boldness and acknowledging that “[Halsey’s] accomplishments prior to the Battle for Leyte Gulf were spectacular,” he was downright insulting in his assessment of Halsey’s performance at Leyte. “[Halsey’s] judgments were not equal to his boldness” and “The U.S. Navy will have learned the greatest lesson of the Battle for Leyte Gulf if it concludes that in the supreme commander it is brains that matters [sic] most,” Brodie wrote.

Then in November, Life magazine, one of the most widely read magazines in America at the time, published an article by Gilbert Cant, the very title of which cut Halsey to the quick. “Bull’s Run: Was Halsey Right at Leyte Gulf?” placed the whole matter into the glaring spotlight of national attention. Cant’s article, though not insulting as Brodie’s had been, nonetheless caused Halsey’s ego no small pain when it asked in extra large, bold print “Did a Japanese blunder save an American Army and Fleet from a Halsey mistake?” Photographs of Halsey and Kinkaid appeared above the title, juxtaposed to suggest that the two were staring at one another in adamant defiance.

The controversy continued for years with periodic flare-ups that rankled Halsey and sometimes spurred him to action and other times did not. On 31 October 1953, a New York Herald-Tribune article, “Leahy Hits Halsey on Leyte Battle,” quoted Admiral Leahy, Roosevelt’s chief of staff, as having said about Halsey’s northward trek, “We didn’t lose the war for that but I don’t know why we didn’t.” Leahy concluded his comments with “Halsey went off on a little war of his own.” Halsey did not respond to this, though it must have been difficult for him to restrain himself.

Admiral Kinkaid, through all this, remained quiet. For a decade, he made no public comment in response to Halsey’s allegations. In 1949, King, writing from his room at Bethesda Naval Hospital while recovering from a stroke, began querying Kinkaid about his actions at Leyte Gulf in a series of letters that spanned several months of back-and-forth correspondence. King seemed obsessed with finding out why Kinkaid had not sent out his own aircraft to search the San Bernardino Strait area instead of assuming that Halsey was there on guard. The letters have the underlying tone of a witch hunt, though the actual wording is cordial. Admiral King seemed intent upon fixing at least some of the blame for the Samar debacle on Kinkaid.

In Kinkaid’s final letter to King, he wrote: “I believe that Halsey made a serious mistake and I regret that he did not acknowledge it in his book instead of his shabby references to me. I have refused to be drawn into a controversy on the subject because no good could come of it.”

But in 1955, Kinkaid relented and decided, at last, to fight back. Hanson Baldwin published an account of the battle in his book, Seafights and Shipwrecks, and for added interest invited both Halsey and Kinkaid to append their comments to his account. Both agreed, and the two locked horns indirectly over Baldwin’s piece.

Halsey’s tone was strident and defensive but he refrained from any further attacks on Kinkaid. Kinkaid, on the other hand, vented some of his long pent-up fury with comments like “[Halsey] apparently overlooks the fact that the absence of TF 34 from San Bernardino Strait precluded the total destruction of Kurita’s force on the spot, to say nothing of the loss of American lives and ships of the CVE force.”

Kinkaid spoke out again in a 1960 interview. This time he was less confrontational, perhaps because Halsey had died the year before. “Halsey spent ten years or more trying to justify his action. . . . Some of his efforts to justify it were at my expense. I don’t mind that so much, but I don’t think his logic was very good.”

The argument did not just take place between Halsey and Kinkaid. Many others had their own views and expressed them. John Thach, McCain’s air operations officer during the battle and a highly respected aviator, supported Halsey’s decision to go north, believing that Halsey had had the vision to look beyond the landings at Leyte. Thach said, “If I were Halsey and had the whole thing to do over again, even knowing what’s been written in all the books, I’d still go after those carriers.” In an interview conducted as part of the U.S. Naval Institute’s oral history program, Admiral Bogan, who commanded Halsey’s Task Group 38.2 at Leyte Gulf, summed up his thoughts on the matter by saying, “It’s a long story and it will never be resolved, except that I’m clear in my own mind that it was a great mistake on Halsey’s part.”

With a half-century gone by in which to make a judgment, and realizing that no judgment will ever be final in this matter, what should history record in terms of this Halsey-Kinkaid controversy? Who is to be praised and who is to bear the burden of error? And just what errors were committed?

The answer is that both men are to be praised for much of what they did, but both must also bear a measure of the blame for what went wrong.

Kinkaid erred by making assumptions. The reasons for these erroneous assumptions are understandable. But, as Carl von Clausewitz noted, much friction lies waiting for the incautious commander, and the fog of war is thick under even the most routine circumstances. In war, assumptions must never be made if there are any means of verification available.

Kinkaid assumed that Halsey was covering San Bernardino Strait. In light of the vague messages sent by Halsey (and Kinkaid could not have known they were vague), this assumption makes sense. But in the final analysis it was a mistaken assumption and Kinkaid’s fault lies in not attempting verification until it was too late to have the desired effect.

Halsey’s error was the more egregious. Without Halsey’s mistake, Kinkaid’s error is erased and the Battle of Leyte Gulf has a significantly modified outcome. One is tempted to point to a number of Halsey’s actions and classify them as errors: his misunderstanding of his mission; his going north after a decoy force; his vague communications; his misreading of Nimitz’s “Where is TF 34?” message; his emotional response to Nimitz’s message; his attempts to fix the blame on Kinkaid. But in truth all of these points lose their significance in light of a single error Halsey made. Had Halsey divided his forces before going north, had he left part of his tremendous combat capability behind at San Bernardino Strait, instead of taking the entire Third Fleet with him, all of the other errors would be canceled out. It would not have mattered that Halsey saw his mission as offensive rather than defensive. No one would have cared that Ozawa’s force was an impotent decoy. His vague messages would not have mattered and would have remained folded away in the yellowed pages of communication logs rather than being subjected to the scrutiny of the world. Nimitz would never have been compelled to write his misunderstood message. And Bill Halsey and Tom Kinkaid would have remained friends until death. In short, the world would never have wondered what went on at Leyte Gulf.

If Halsey’s reluctance to divide his fleet was at the heart of the matter, what was it that caused him to make that tragic decision? His Mahanian War College training was most likely an ingredient in his thinking. Seven years after the war, Halsey explained his reasoning in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine:

I could guard San Bernardino with Task Force 34 while I struck the Northern Force with my carriers. Rejected. The heavy air attacks on Task Group 38.3 which had resulted in the loss of the Princeton indicated that the enemy still had powerful air forces and forbade exposing our battleships without adequate air protection. It is a cardinal principle of naval warfare not to divide one’s force to such an extent as will permit it to be beaten in detail. If enemy shore-based planes joined with his carrier planes, together they might inflict far more damage on my half-fleets separately than they could inflict upon my fleet intact.

At the time of the battle, Halsey did not know how severely hampered was Japanese air power, so he cannot be blamed for overestimating the capability of his enemy. The loss of Princeton must have been a sobering event, and it is no wonder that Halsey factored that into his thinking. And what he says about dividing the fleet “to such an extent as will permit it to be beaten in detail” is certainly true. But to assert that the Third Fleet could not be divided without risking its being “beaten in detail” is unreasonable. This was a tremendously potent force that could well afford to be divided. Fleets are, after all, meant to be divided. Otherwise, why have that complicated system of task forces, groups, units, and so on? Why have other admirals in the fleet?

Halsey’s point about leaving the battleships at San Bernardino Strait without air cover is well taken and is something apparently overlooked by Kinkaid in his continual assertions that leaving TF 34 behind was “exactly correct in the circumstances.” But why not leave behind an air group to defend the battleships when daylight returned? Admiral Lee’s suggestion that one or two CVLs would be all that was needed has a great deal of merit.

There may be another factor in this equation. Halsey was embarked in a battleship. Since the night approach of Kurita called for the gunships of the Third Fleet as the logical counter, breaking off the battleships to remain behind at San Bernardino would have required Halsey to remain as well. Halsey’s belief that Ozawa’s Northern Force represented the “big battle,” coupled with his frustration at having missed all of the other large fleet engagements of the war, may well have motivated him to send the battleships, including his flagship, New Jersey, and therefore himself, north.

This is, of course, speculation, and there is no way to know for certain what caused Bull Halsey to make that fateful decision. The world will continue to wonder.

In 1936, the Naval War College published Sound Military Decision, a book that included the observation that in naval warfare “mistakes are normal, errors are usual; information is seldom complete, often inaccurate, and frequently misleading.” This was certainly true at Leyte Gulf, and the War College, in the spirit of gleaning lessons learned, embarked upon a special postwar project, headed by Commodore Richard W. Bates, the purpose of which was to prepare a detailed “strategical and tactical analysis” of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The foreword to the study explains the need for the analysis “because of the nature of the Allied victory at Leyte Gulf and the numerous controversies which have arisen concerning it. . . .” The resulting study was indeed detailed—consisting of more than two thousand pages—and promised to be a valuable document that would achieve the stated purpose of provoking “earnest thought among prospective commanders and thus to improve professional judgment in command.” Unfortunately, the study ended at the Battle of Surigao Strait; the controversy over the action at Samar was never analyzed. The foreword to the fifth and final volume explained the sudden termination of the project as follows: “For reasons beyond the control of the Naval War College, the Chief of Naval Operations decided to conclude the battle analyses with the Battle of Surigao Strait and to discontinue all other planned volumes.”

This was a most unfortunate decision. Any organization does well to encourage introspection and self-criticism of a constructive nature. The Navy probably cheated itself of a valuable document by terminating Commodore Bates’s project before it got to the stages of the battle most needing such a look.

Halsey and Kinkaid were not alone in their errors at Leyte Gulf. Nimitz shares a small measure of the blame for allowing the caveat to be appended to Halsey’s orders and for not recognizing the danger signs so apparent in Halsey’s letter to CINCPAC before the battle. MacArthur should not have permitted the awkward communications setup between Halsey and Kinkaid that allowed so much delay and confusion. Bogan, Lee, and Mitscher should have pressed Halsey with their concerns when they felt he was making a mistake. And Sprague should have seen to the rescue of the men who were forced to abandon his ships during the action off Samar.

While it is important for the sake of learning to remember and evaluate the errors made, it is also important for the sake of the nation’s heritage to remember what was achieved. Admiral Halsey, for example, deserves a great deal of credit for keeping the Japanese off balance by his bold actions. It was Halsey who caused the acceleration in schedule that brought the Americans to the Philippines before the Japanese had completed their preparations, and it was his aggressiveness that caused his enemy to commit their precious air assets at Formosa. On 6 January 1945, President Roosevelt delivered what would prove to be his last State of the Union Address. Among the many things he reported to the Congress on that wintery day was the following:

Last September … it was our plan to approach the Philippines by further stages, taking islands which we may call A, C, and E. However, Admiral Halsey reported that a direct attack on Leyte appeared feasible. . . . Within the space of 24 hours, a major change of plans was accomplished which involved Army and Navy forces from two different theaters of operations—a change which hastened the liberation of the Philippines and the final day of victory—a change which saved lives which would have been expended in the capture of islands which are now neutralized far behind our lines.

No small accolade from no small man.

Admiral Kinkaid, like Halsey, deserves a great deal of credit for his performance of duty before Leyte Gulf, and at Leyte his leadership, overall, was excellent. The amphibious landings, which were the primary mission of U.S. forces there, were superbly handled. His postwar reticence to participate in the dispute between Halsey and himself is admirable, and his eventual change of heart on that is fortunate for historians because it sheds some additional light on the controversy.

Without General MacArthur there might not have been a battle at Leyte Gulf. His persistence was instrumental in bringing about the liberation of the Philippines at an earlier time than would otherwise have occurred, and his ability to sway Roosevelt was pivotal to the whole matter.

Admiral Spruance conducted a brilliant campaign in the Marianas, though his decision to stay close to the islands to defend the amphibious forces was then, and is even today, a controversial one. The irony is that Spruance was criticized for doing exactly the opposite of what Halsey was criticized for doing at Leyte Gulf. The comment has been made many times, once by Halsey himself, that the war in the Pacific would have been better served had Halsey commanded at the Marianas and Spruance at Leyte Gulf.

Admiral Oldendorf’s conduct of the battle in Surigao Strait was outstanding. His planning was flawless and his execution nearly so. Only the understandable errors that led to the unfortunate damage to Albert W. Grant mar an otherwise perfect performance.

Admiral Clifton Sprague deserves recognition for his conduct at Samar. Responding to a desperate situation with no time to plan and with few assets at his disposal, he managed to keep a cool head and made the best of a very bad situation.

One is reluctant to begin singling out individual ships and their commanders because all played important roles and because there are many examples of outstanding performance that deserve recognition. But in the case of the Taffy 3 escorts, an exception would be in order. What the men in those ships did on that October morning off Samar deserves to be a focal point of the nation’s naval heritage, ranking with John Paul Jones’s epic “I have not yet begun to fight” battle. Commander Ernest E. Evans received the Medal of Honor, posthumously, for his incredible courage while taking the Johnston “in harm’s way.” One of the buildings at the Navy’s Surface Warfare Officers School in Newport, Rhode Island, rightfully bears his name. But there should be more tributes. A statue commemorating the deeds of those ships and the men who crewed them in the Battle of Leyte Gulf should be erected in the nation’s capital so that all Americans will be reminded of the kind of courage and sacrifice this nation can produce when circumstances require.

War is probably mankind’s greatest folly. It is wasteful, tragic, and frequently unnecessary. But when it does occur, in an ironic twist, it brings out what is in some ways best about mankind. Many brave men, American and Japanese, fought at Leyte Gulf. Too many died there, while others live even today as flesh-and-blood monuments to those virtues that shine forth from the wreckage and tragedy of war. Admirals Halsey, Kinkaid, and Sprague, General MacArthur, Captain Adair, Commanders Evans and McCampbell, Lieutenant Digardi, Petty Officer Roy West, Seaman Billie, and the thousands of others like them are to be honored just for being there at Leyte Gulf—for doing their jobs under arduous circumstances, for serving and sacrificing for their country. The causes for which these men fought and sacrificed have faded with time; the machines they used to carry out their deadly business are now rusted relics of another era; the sands have swallowed their footprints and the waters show no trace of their wakes. But the glory of their deeds will never be tarnished by time.

*Kurita’s navigational track reveals that he turned south again for a while in the afternoon of the twenty-fifth—as though headed back to Leyte Gulf—before reversing course again and entering San Bernardino Strait.