Max Immelmann’s chance to test the Fokker Eindecker in action came on 1 August 1915, when he took off with Boelcke to attack some BE.2cs, which were bombing the German airfield at Douai. The subsequent official report tells the story:

At 6 am on 1 August Leutnant Immelmann took off in a Fokker fighting monoplane in order to drive away the numerous (about ten to twelve) enemy machines which were bombing Douai aerodrome. He succeeded in engaging three machines showing French markings [in fact they were British – author] in the area between Arras and Vitry. Heedless of the odds against him, he made an energetic and dashing attack on one of them at close quarters. Although this opponent strove to evade his onslaught by glides and turns and the other two enemy aircraft tried to assist the attacked airman by machine-gun fire, Leutnant Immelmann finally forced him to land westward of and close to Berbíères after scoring several hits on vital parts of the machine. The inmate, an Englishman (instead of an observer he had taken with him a number of bombs, which he had already dropped) was severely wounded by two cross-shots in his left arm. Leutnant Immelmann immediately landed in the neighbourhood of the Englishman, took him prisoner and arranged for his transport to the Field Hospital of the 1st Bavarian Reserve Corps. The machine was taken over by the Abteilung. There was no machine-gun on board. A sighting device for bomb-dropping has been removed and will be tested.

Immelmann’s second BE, and his third aerial victory, was encountered on 1 September 1915, his birthday. He was circling over Neuville village, acting as escort to a German artillery-spotting aircraft, when he sighted the British machine, which he erroneously described as a:

… Bristol biplane which is heading straight towards me. We are still 400 metres apart. Now I fly towards him; I am about 10–12 metres above him. And so I streak past him, for each of us has a speed of 120 kilometres an hour. After passing him I go into a turn. When I am round again, I find he has not yet completed his turning movement. He is shooting fiercely from his rear. I attack him in the flank, but he escapes from my sights for a while by a skilful turn. Several seconds later I have him in my sights once more. I open fire at 100 metres, and approach carefully. But when I am only 50 metres away, I have difficulties with my gun. I must cease fire for a time.

Meanwhile I hear the rattle of the enemy’s machine-gun and see plainly that he has to change a drum after every 50 rounds. By this time I am up to within 30 or 40 metres of him and have the enemy machine well within my sights. Aiming carefully, I give him about another 200 rounds from close quarters, and then my gun is silent again. One glance shows me I have no more ammunition left. I turn away in annoyance, for now I am defenceless. The other machine flies off westward, i.e. homeward.

I am just putting my machine into an eastward direction, so that I can go home too, when the idea occurs to me to fly a round of the battlefield first, for otherwise my opponent might think he had hit me. There are three bullets in my machine. I look round for my ‘comrade of the fray’, but he is no longer to be seen. I am still 2500 metres up, so that we have dropped 600 in the course of our crazy turns.

At last I discover the enemy. He is about 1000 metres below me. He is falling earthward like a dead leaf. He gives the impression of a crow with a lame wing. Sometimes he flies a bit and then he falls a bit. So he has got a dose after all.

Now I also drop down and continue to watch my opponent. It seems as if he wants to land. And now I see plainly that he is falling. A thick cloud rises from the spot where he crashes, and then bright flames break out of the machine. Soldiers hasten to the scene. Now I catch my first glimpse of the biplane I intended to protect. It is going to land. So I likewise decide to land, and come down close to the burning machine. I find soldiers attending to one of the inmates.

He tells me that he is the observer. He is an Englishman. When I ask him where the pilot is, he points to the burning machine. I look, and he is right, for the pilot lies under the wreckage – burnt to a cinder. The observer is taken off to hospital …

Immelmann’s description admirably sums up the weakness and the strength of the BE.2 in combat. First, Immelmann easily completes his turn before the BE pilot is anywhere near completing his, enabling him to latch on to the British aircraft’s tail and press home his attack; and second, the BE displays its inbuilt stability after the pilot, as Immelmann learns later, is shot through the neck and killed. The aircraft goes out of control, but literally rights itself and resumes level flight before departing again. This process happened several times before it hit the ground and the observer, who lived to tell the story, was thrown clear.

By the autumn of 1915, the losses suffered by the BEs and other reconnaissance aircraft at the hands of the Fokkers had risen to such an alarming degree that the RFC decreed that all reconnaissance sorties must be escorted. The immediate solution, though not a good one, was for one BE to act as the escort while the other took its photographs. This tactic ended too often in both BEs being destroyed. What was needed was a dedicated fighter aircraft.

The French rose to the challenge first with the introduction of the single-seat Nieuport 11 biplane, which was deployed in the late summer of 1915, albeit in small numbers. Nicknamed ‘Baby’ because of its diminutive size, it had a machine-gun mounted on the upper wing, enabling the pilot to fire forwards over the arc of the propeller. The Nieuport 11 also served with the RFC and the RNAS and was built under licence in Italy, where it remained the standard fighter type until 1917.

The Nieuport 11 virtually held the line against the Fokker Eindecker until the introduction of two British fighter types, the FE.2b and DH.2. The original FE.2a was completed in August 1913, but it was a year before the first twelve aircraft were ordered, the first of these flying in January 1915. Had matters moved more quickly, and production of the FE.2 been given priority, it is possible that the Fokker Eindecker would never have achieved the supremacy that it did. The first FE.2b flew in March 1915. In May a few production examples arrived in France for service with No. 6 Squadron RFC at Abeele, Belgium, but it was not until January 1916 that the first squadron to be fully equipped with the FE, No. 20, deployed to France. The FE.2b was a two-seat ‘pusher’ type aircraft, powered by a 120-hp Beardmore engine and armed with one Lewis gun in the front cockpit and a second on a telescopic mounting firing upwards over the wing centre-section. It was slightly slower than the Fokker E.III but a match for it in manoeuvrability. Later in the war the FE was used in the light night-bombing role. The FE.2d was a variant with a longer span. FE.2 production totalled 2325 aircraft.

The first dedicated RFC fighter squadron to deploy to France was No. 20, equipped with FE.2bs. It was followed, on 8 February 1916, by No. 24 squadron, armed with Airco (Aircraft Manufacturing Company) DH.2s. Designed by Geoffrey de Havilland, the DH.2 was a single-seat ‘pusher’ type, whose prototype had been sent to France in July 1915 for operational trials; unfortunately, it was brought down in enemy territory on 9 August. The DH.2 was powered by a 100 hp Monosoupape engine and was armed with a single Lewis gun mounted on a pivot in the prow, enabling it to be traversed from left to right or elevated upward and downward. In practice, pilots found this arrangement too wobbly and secured the gun in a fixed forward-firing position, using the whole aircraft as an aiming platform. Rugged and highly manoeuvrable, the DH.2 was to achieve more success in action against the Fokkers than any other Allied fighter type. No. 24 Squadron was commanded by Major L.G. Hawker, who on 25 July 1915, while flying a Bristol Scout of No. 5 Squadron, had been awarded the Victoria Cross for engaging three enemy aircraft in quick succession and shooting one down. It soon became one of the best-known Allied air units. It gained its first victory on 2 April 1916 and claimed its first Fokker on the 25th of that month. From then on its tally rose steadily. In June 1916 its pilots destroyed seventeen enemy aircraft, followed by twenty-three in July, fifteen in August, fifteen in September and ten in November. On 23 November, however, Major Hawker was shot down by an up-and-coming German pilot named Manfred von Richthofen. Some 400 DH.2s were built, many being shipped to the Middle East after they became obsolete on the Western Front.

The BE.2 was to have been replaced in first-line service during 1916 by another product of the Royal Aircraft Factory, the RE.8. Nicknamed ‘Harry Tate’ after the Cockney comedian, the RE.8 reconnaissance and artillery spotting aircraft resembled a scaled-up BE.2, but it had a much sturdier fuselage and far better armament. The first aircraft were delivered in the autumn of 1916 but were grounded after a series of accidents that led to the redesign of the tail unit. The RE.8 was subsequently very widely used, equipping thirty-three RFC squadrons. Like the BE.2, it was far too stable to be agile in combat and suffered serious losses, usually having to operate under heavy escort. It was not until the beginning of 1917 that the RFC’s reconnaissance squadrons in France began to receive a really viable aircraft, the Armstrong Whitworth FK.8. Designed by the talented Dutchman Frederick Koolhoven, who joined Armstrong Whitworth of Coventry in 1914, the FK.8 army cooperation aircraft – known to its crews as the ‘Big AW’ or ‘Big Ack’ – first flew in May 1916 and eventually equipped nine RFC squadrons at home and overseas. About 1400 were built in total, serving in the reconnaissance, patrol, day and night-bombing and ground-attack roles throughout 1917 and 1918. The FK.8 was well liked by its crews, partly for its excellent flying qualities and partly because of its ability to absorb a great deal of battle damage.

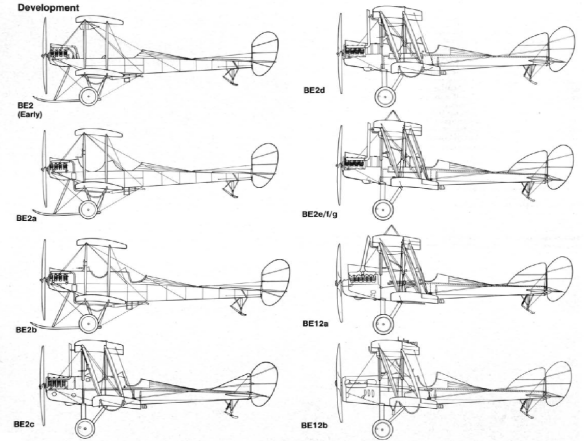

Two more variants of the BE.2, the 2d and 2e, appeared before production ceased late in 1916. The type ended its combat career with the RFC’s home defence squadrons, where it enjoyed considerable success against German airships.