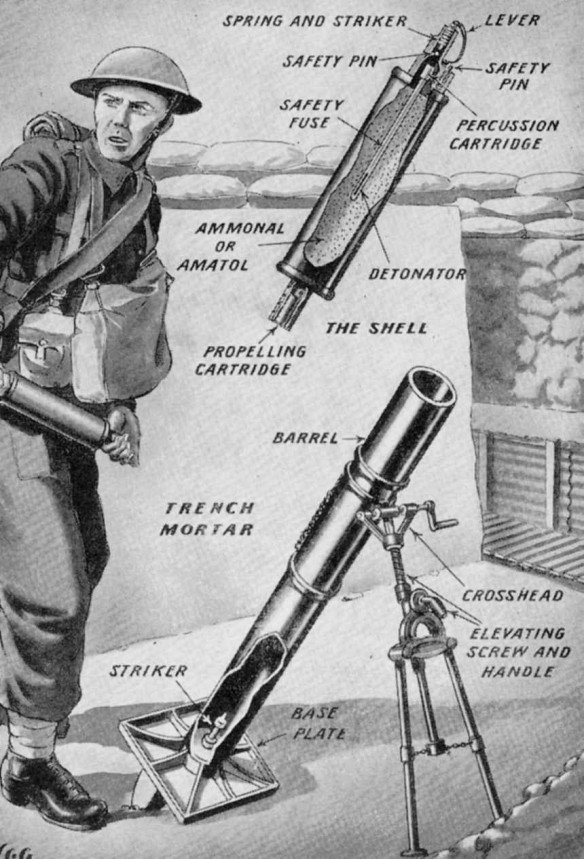

Diagram of Stokes 3in mortar showing its method of operation.

Gunpowder weapons termed as mortars had been in use with artillery as early as the fifteenth century, and a huge example was deployed at the siege of Constantinople in 1453 where it was used to batter the walls and buildings of the great city by the Turkish Army. By the sixteenth century, gun founders working in England such as Peter Baud (sometimes written as Bawd) along with Peter van Collen were casting mortars with calibres of 11in and 19in, which more than delighted King Henry VIII, who rejoiced in having a powerful artillery force. Such huge calibres meant these weapons were best used in siege operations against walled cities or castles to fire projectiles at extremely steep angles of elevation to reach over the walls at very short ranges. These types of mortars retained enormous calibres for many years and remained part of the artillery train when on campaign. Gradually the size and weight of these weapon designs was reduced to make them more mobile, which also allowed them to be more versatile in the range of targets they could be used to engage. Around 1674, the Dutch military engineer Baron Menno van Coehorn (variations in the spelling of his name include Coehoorn or Cohorn) developed a mortar which fired a projectile weighing 24lbs and was used in the siege against the Dutch city of Grave during the closing stages of the Eighty Years War. This design was much more compact than anything seen previously and light enough to be moved on a horse-drawn wagon, thereby giving the infantry its first portable mortar to use against field works.

Over the next 240 years, mortars were in continuous use by armies in various wars and some of these designs reached enormous calibres. For example, at the siege of Cadiz in Spain in 1810, the French deployed mortars with 13in calibres along with other artillery. At the siege of Antwerp in 1832, the French once again deployed gigantic mortars with calibres up to 24in. The British Army also considered adopting even larger calibres when the Irish-born civil engineer Robert Mallet proposed a built-up mortar with a calibre of 36in which he intended for use during the Crimean War. A series of events meant that the war had ended in February 1856 before his design was ready, but it continued to be developed. On being test-fired, it showed design flaws and the weapon was scrapped without firing a shot in anger. The British Army still had mortars of 13in calibre in service during the nineteenth century, and both the Confederate and Union armies used mortars of this size during the American Civil War. Some of these weighed over 7.5 tons, such as the ‘Dictator’ used by the Union Army at the siege of Petersburg in 1862, and were so large they had to be transported by train. Gradually the calibre of mortars was reduced again but they were still part of the artillery branch.

It was not be for another fifty years, during the early battles of the First World War in October 1914, that a real need for some form of weapon capable of firing explosive shells at short range into enemy positions was requested. By the end of that year, both sides had halted their initial sweeping movements which were aimed at trying to outflank one another and had kept the fighting mobile. The opposing armies now settled into their respective positions and started to ‘dig in’ and create trench systems reminiscent of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. In that war, the Russian defenders around Port Arthur had dug a series of trenches which had to be captured by attacking Japanese troops who emerged from their own trenches which surrounded the besieged location.

The trench system which developed to snake across France and Belgium eventually extended from the Swiss border to the Channel Coast, a distance of almost 500 miles, in a virtually unbroken line of defences and counterdefences. At times these positions were only a few hundred yards apart and in other places they were so close that soldiers could throw hand grenades into one another’s positions. It was a stalemate and some form of weapon was needed which would allow the troops to fire projectiles further than they could throw grenades without unduly exposing themselves to enemy fire. It also had to be sufficiently compact and light enough to be moved around the trenches. Such a weapon would release the infantry from their dependency on the artillery for support, which would allow the guns to be used to fire on other targets such as enemy artillery positions, ammunition supply points and lines of communications.

General Sir John French, Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France, took up the call and asked for some ‘special form of artillery’ which his troops could fire from their trenches to ‘lob’ bombs or grenades into German positions. Designs soon began to emerge, many of which were dismissed as being impractical. For example, one design hastily produced in France was based on nothing more original than a piece of 3.7in cast iron drainpipe to fire equally crude projectiles filled with explosive. Mortars which had been made in the mid-nineteenth century, including some which may have been used during the Crimean War, were rushed to the Front, where the troops could not believe the antiquity of these weapons which they were now expected to use.

More surprising was the fact that stocks of ammunition for these weapons had been located and were of equal vintage, and units known as the ‘Trench Mortar Service’ were raised to use these weapons. The serviceability of these weapons was uncertain and methods to fire them from a safe distance had to be devised in the event that they should burst on being fired. At Pont de Hem near Estaires in November 1914, two artillery officers and nine gunners using these obsolete weapons were formed into a group and referred to themselves as the ‘Suicide Club’. Through trial and error they managed to operate these mortars and even achieve a modicum of success, firing projectiles out to ranges of 300 yards.

Whilst these heavily dated mortars and extemporised designs were sound in principle, what the troops in the front line trenches really needed urgently was a properly produced weapon. In an attempt to produce something quickly, frustrated British troops began making extemporised weapons, which included the Second Army producing mortars using brass shell cases from a factory at Armentières. The Germans, on the other hand, were far more organised and had minenwerfers (‘mine throwers’) which had been produced by the huge armaments industry of Krupp. When war broke out, the German Army had 116 medium and forty-four heavy versions of these weapons, which were categorized as trench howitzers and as such were part of the artillery. The levels of these weapons increased as the war progressed so that by the middle of 1916 there were some 1,684 of all types in service, and by the end of the war the number had increased to around 17,000 of all types.

Meanwhile in England a more promising design was being developed in the workshops at the Woolwich Arsenal in London. This was the so-called ‘Twining’ pattern, and weapons were hurriedly sent to France in January 1915. Unfortunately they proved just as unsatisfactory as the drainpipe mortars when eight out of the eleven weapons burst on being fired in the space of ten days. Such an unreliable track record only served to produce a not un-natural reluctance among the troops to fire the weapon. Captured examples of German weapons had been sent back to England to be copied and some had been sent to France, but what was needed was a weapon design which had been properly developed and field-tested before being sent to front line troops. In 1918, the Hungarian Army was using a basic mortar design of 90mm calibre known as the Magyar, which was a very simple tube affair elevated and mounted on a baseplate, but worked nevertheless and around forty-eight of these weapons were issued to a division.

One person who applied himself to the task of developing a new weapon to the requirements of the army was Frederick Wilfred Scott Stokes, later to become Sir Frederick when he was knighted in 1917. He applied his engineering expertise to the problem and contrived a design which was simple and really no more than an improved idea based on the initial drainpipe design. Indeed, he personally described his idea as being, ‘little more than a piece of coarse gas-piping, sitting dog-fashion on its hind quarters and propped up in front by a pair of legs corresponding to the canine front equivalent’. Stokes was born in Liverpool in 1860 and apprenticed to the Great Western Railway and took a keen interest in engineering, being involved with designing bridges for the Hull & Barnsley Railway. He later joined the Ipswich-based engineering firm of Ransomes & Rapier and became Managing Director of the company. In 1915, he was working in the Inventions Branch of the Ministry of Munitions when he devised his idea for a new mortar, which would bear his name as the Stokes mortar. Stokes later received a financial reward from the Ministry of Munitions in recognition of his work along with a royalty payment of £1 for each of his mortar bombs used during the remainder of the war.

Stokes approached the design as a means to deliver a HE bomb at short ranges fired at a steep angle to plunge into enemy trenches, where it would explode on impact. He used a smoothbore barrel, which is to say it did not have rifling grooves inside to impart a spinning action which would stabilise the bomb in flight. The base of the barrel rested on a metal baseplate and the upper end was supported on a bipod rest which could be traversed left and right. By adjusting the height of the legs the angle of fire could be altered. The projectiles were called bombs and produced as very simple cast iron cylinders filled with a HE compound. The fuse was the same type as fitted to the Mills hand grenades and fitted with a safety pin in the nose of the bomb. In the base a 12-bore shotgun-type cartridge filled with ballistite compound, a fast-burning smokeless powder, provided the propellant. By 1917, Stokes had standardised his bombs to 76mm (3in) and a bomb 12.6lbs bomb could be fired out to a range of 820 yards. The later version, known as the 3in Mk 1, fired a bomb weighing 10lbs out to a range of 2,800 yards. By the end of the war, the British Army had 1,636 Stokes mortars in service on the Western Front.

After the war, many Stokes mortars were used in the local wars of South American countries – the Paraguayan Army used them during the Chaco War of 1932, for example. The newly-created state of Poland purchased about 700 Stokes mortars between 1923 and 1926, which led to an unlicensed copy known as the Avia wz/28 being produced. The weapon had to be abandoned in 1931 because the bombs it fired were based on the French Brandt design and a licence to manufacture the ammunition was denied.