The apparently deliberate German practice of spreading terror wherever they went filled the roads from Belgium and Alsace-Lorraine with civilian refugees – mostly women, children and old men wearing their Sunday best. Seeking safety, they tramped forlornly westward in their thousands, having piled such possessions as they had been able to save onto carts drawn by oxen. Their strange accents occasionally caused them to fall victim to French fears that German spies were concealed among them. In the fevered atmosphere of August 1914, when advertisements for beef stock cubes produced by a supposedly German company had to be removed because rumour insisted that they contained concealed codes to guide German saboteurs to strategic points, suspected spies were apt to be dealt with summarily. A young officer noted that ‘The most fantastic rumours are going around; everyone is seeing spies unbolting railway track or trying to blow up bridges,’ whilst a British officer warned that ‘the French are brusque in their methods with spies’.

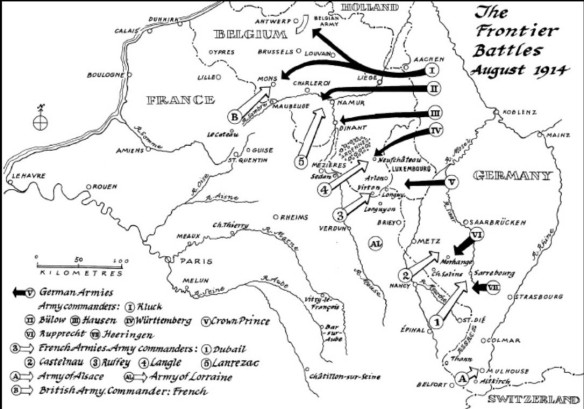

The flood of refugees from Belgium was one indicator of the strength of the German advance there which was already forcing Joffre to modify his dispositions. He had expected that some German troops would pass through southern Belgium. A flurry of German railway-building in the northern Rhineland, and particularly around the city of Aachen, in recent years had not gone unnoticed by French intelligence; who, however, had convinced themselves that German troops would not pass north of the line formed by the Rivers Sambre and Meuse. Having miscalculated the number of troops Germany could bring to bear in the west in the first weeks of the war, Joffre gravely underestimated the size and direction of the coming blow. Not only had the Germans kept a bare minimum of troops to face the Russians in the east, but they had put reservists into the front line to reinforce the hammerhead of three armies that was swinging through Belgium aiming to envelop the French left flank. In reality, those armies would comprise three-quarters of a million troops.

In France, reliance on reservists was seen by the high command and the Right as both militarily and politically suspect, and less had been invested in their training than in Germany. As Joffre later confessed, because the French would not have used what they considered inferior troops in this way, it did not occur to him that the Germans might do so. Joffre and his staff were complacent about and irritated by repeated warnings from General Lanrezac, commanding Fifth Army, about the potential German threat to his left flank. After all, Sordet’s cavalry corps had ridden deep into southern Belgium from 6 August and returned ten days later without encountering any significant body of German troops, for the good reason that none was there. Sordet’s men – elegantly uniformed hussars, lancers and chasseurs, helmeted dragoons and cuirassiers whose steel breastplates were concealed by covers – had been cheered as they rode through Belgium, but they had failed to bring any material aid to the beleaguered Belgian army and achieved little save to wear out their mounts. Their reports seemed to confirm Joffre’s preconceptions and to justify his reassuring Lanrezac on 14 August that ‘the Germans have nothing ready’ beyond the Meuse.

In these days when every history student has heard of the ‘Schlieffen plan’, we should remember that Joffre was not gifted with the powers of hindsight enjoyed by his post-war critics. The general German westward advance through Belgium did not begin until 18 August, after the forts of Liège had been pounded into surrender by the heaviest guns available. Brussels fell on the 20th – the date, Joffre claimed, ‘when for the first time we had precise information about what was going on north of the Meuse’. His response was to attack. If there was a larger than expected German presence in Belgium, thought his chief of staff, ‘so much the better: that will allow us to cave in their centre’. Joffre therefore proceeded immediately with the next phase of his planned offensive, sending Third and Fourth Armies across the Belgian frontier into the Ardennes forest, where he believed the Germans must be weak. Eight army corps, roughly a third of a million men, would advance on a 60-kilometre front, broadly between Bouillon and Longwy.

The densely wooded hills of the Ardennes, traversed by few roads but intersected by many streams that turned the ground marshy in places, made an uninviting battleground. Beyond the occasional pasture fenced with barbed wire, only the cultivated areas around the settlements in the river valleys afforded opportunities for manoeuvre. But Joffre did not intend his armies to fight there, only to pass through. French columns entered the forest virtually blind on the mist-shrouded morning of 22 August, assured that they could expect no contact with the enemy that day. Once again French intelligence and reconnaissance were inadequate, and the French deployment invited catastrophe. They entered the Ardennes not in a connected line but in a stepped or echelon formation, with the left flank corps leading. As they did so they collided with the German Fourth and Fifth Armies.

German scouts kept their infantry commanders better informed, and in the series of disconnected encounters that ensued German troops repeatedly demonstrated the superiority of their training and small unit tactics. If they had no more machine guns than the French, their machine-gun companies showed greater proficiency in deploying and concealing their weapons. If the French 75 was a fine gun, cooperation between infantry and artillery left much to be desired. When the sun burned off the mist many French batteries were caught out in the open by German gunners, who made short work of them. German riflemen in their grey uniforms were less conspicuous than their enemies, whose only concession to camouflage was a blue-grey cover for their red-topped kepis. The glint of mess-tins strapped on top of the French infantrymen’s packs, even more than their red trousers, helped German marksmen draw a bead. French officers, identifiable by their shorter coats, paid a heavy toll. A staff officer of Third Army trying to glean information met an old friend emerging from the fight: ‘He told me how his brigade had met disaster … of his commander killed at his side, of whole ranks of men mown down by machine guns; of the horror of fighting in the fog; of a frightful nightmare … And this officer, whose courage I had no reason to doubt as he was known to me, put his hands over his eyes as if to see no more of this terrifying spectacle.’ Even in areas of this vast battle-zone where the Germans did not enjoy numerical superiority, they took the fight aggressively to the enemy, infiltrating between French units and making use of cover. One German division succeeded in putting the French 17 Corps to flight.

On the French side command and control often broke down in the excitement of combat, and the hesitations of some commanders in terrain affording such poor visibility left the flanks of neighbouring units exposed. Some French units, notably 3rd Division of the Colonial Corps, found their retreat cut off by German infantry working their way through the woods to their rear and by German artillery laying down a curtain of shrapnel. These marines, hardened professional soldiers and the successors of the men who in 1870 had made their last stand at Bazeilles near Sedan (only 40 kilometres away), sold their lives dearly but were surrounded and cut to pieces by units which included German reservists. The division lost 10,500 out of 17,000 men, and several other regiments suffered over 30 per cent losses.

Over on the right flank of Third Army, 23-year-old Desiré Renault described how:

The battle began at dawn. I fought all day, and was very lightly wounded the first time by a bullet that passed through my pack, which I had placed in front of me, hit my hand, went through my greatcoat and grazed my chest. I found the bullet, which I showed to a comrade, Marcel Loiseau, then put it in my purse. I continued the fight, when my comrade Loiseau was hit in the leg. I also saw my lieutenant fall, shot through by a bullet. The battle continued; a great many of my comrades lay dead or dying around me. About three o’clock in the afternoon, while I was firing at the enemy who was occupying a trench two hundred metres away, I was hit by a bullet in my left side. I felt terrible pain, as if someone were breaking my bones. The bullet travelled right down the length of me, passing through my pelvis and lodging above my knee. I immediately experienced great suffering and a burning fever.

Renault crawled into a hole and spent a frightful night tortured by thirst, listening to the groans of the wounded and the bombardment of Longwy by German guns while a machine gun swept the ground around him. The next day the sun brought out swarms of flies drawn by so much blood. Not until the evening was he found by Red Cross workers who rescued him under German fire. Narrowly surviving the bombardment and burning down of the hospital he was taken to, Renault was to spend four years in captivity.

Amongst the thousands killed on 22 August was the writer Ernest Psichari, celebrant of the military virtues, who was shot through the head while directing a battery. The Germans were the clear victors, with significantly fewer casualties than the French. Nevertheless, their losses too had been severe. After the battle they took savage vengeance on the inhabitants of the towns and villages whose little-remembered names evoke the combats of that bloody Saturday – Neufchâteau, Rossignol, Bellefontaine, Tintigny, Bertrix, Virton, Ethe. The French Third and Fourth Armies, decisively repulsed but not routed, withdrew across the French frontier.