A German 5.9 inch howitzer. German artillery outranged French 75 guns during the Battle of the Frontiers.

At five o’clock in the morning on Friday, 7 August 1914 troops of the French 7 Corps under General Bonneau entered Alsace, triumphantly uprooting the German frontier-posts as they advanced. Watched by curious but smiling peasants, they headed up the main road leading eastward from the French bastion of Belfort. French forces that day took the town of Thann, and after a skirmish with outnumbered German defenders stormed into the village of Altkirch. By the evening of 8 August they had entered the industrial centre of Mulhouse, where they were enthusiastically received. A proclamation to Alsatians signed by Joffre announced that ‘After forty-four painful years of waiting, French soldiers once again tread the soil of your noble region. They are the first labourers at the great work of revenge! …’ Now that the day of liberation had arrived, the years since 1871 appeared in retrospect to have been only a foredoomed truce between France and Germany. Already the French government had made the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine a war aim. Like the success of Saarbrücken in August 1870, news of Altkirch and the occupation of Mulhouse caused rejoicing in France.

Bonneau’s men were the southernmost unit in the French deployment of five armies, each of several corps, which extended 300 kilometres along the Franco-German border, from Belfort near Switzerland to beyond Mézières on the River Meuse, facing southern Belgium. The army commanders on both sides were mostly men born in the 1840s or 1850s who had served as young officers in the war of 1870–71. Joffre had seen service (though not action) with an artillery battery during the Siege of Paris. General Dubail, commanding First Army, had first distinguished himself at Spicheren and Borny. General de Castelnau, commanding Second Army, had served in Chanzy’s Army of the Loire. General de Langle de Cary, at the head of Fourth Army, had been an orderly to General Trochu during the Siege of Paris and had been wounded in the chest at Buzenval, while General Lanrezac, commanding Fifth Army, had seen action around Orléans and in Bourbaki’s Army of the East. Now the French army had the opportunity to redeem its earlier defeat and recover its reputation.

Unlike its German counterpart, Plan XVII did not prescribe a particular line of operations: Joffre confided detailed instructions to his army commanders on 8 August, stating his intention to seek battle with all his forces united. Bonneau’s foray into southern (Upper) Alsace, besides its psychological impact, was meant to destroy the Rhine bridges and to support the right flank of Dubail’s First Army as it advanced further north.

Yet despite the comparative ease of his initial advance, Bonneau was hesitant and pessimistic, and his campaign quickly stalled. Not everyone in Mulhouse was glad to see the French, and telephone lines carried news of events to the headquarters of the German Seventh Army at Strasbourg. By the evening of 9 August the Germans had launched their counterstroke. To avoid encirclement, the French evacuated Mulhouse the next day and retreated back across the frontier, fighting several rear-guard actions.

Although the portly, white-moustached Joffre had the appearance of a benevolent station-master, his staff knew well enough that his apparent placidity masked a fierce temper. He knew how to make his authority felt, and did not tolerate failure. If he did not go as far as the excitable War Minister, Adolphe Messimy, who reportedly claimed, ‘Give me the guillotine and I’ll give you victory’, Joffre made it plain that no general suspected of weakness or incompetence could expect to keep his job. Bonneau and some of his subordinates were sacked, the first of dozens of senior generals who, fairly or otherwise, would receive short shrift from him over the coming weeks. A new French verb would gain currency, limoger, meaning to send generals to report at Limoges, far behind the front. (The British equivalent, to stellenbosch, had been coined during the Boer War.) In the face of this first setback Joffre also demonstrated a penchant for creating new armies for particular tasks, which he was to employ several times in the coming weeks. Reinforcing 7 Corps with additional divisions, he designated the new force of 150,000 men the Army of Alsace and put it under the command of General Pau, a veteran who had lost a hand in 1870.

Pau swiftly recovered the ground abandoned by Bonneau, fighting his way back into Mulhouse on 19 August. Yet he proved unable to exploit his success or to provide the support urgently demanded by Dubail. The Germans had fallen back to more defensible positions, and within days Upper Alsace had become a strategic backwater for both sides as heavy fighting developed further north. Pau was shortly ordered to withdraw, and his army was dissolved because its divisions were urgently needed elsewhere. By the end of August French troops in Alsace retained only a toe-hold around Thann and the wooded passes of the Vosges, captured by trained Alpine troops in a series of savage actions simultaneous with the abortive advances on Mulhouse.

Meanwhile, by mid-August the main French concentration was largely complete. From their railheads the troops marched to their assigned positions, suffering from the stifling heat in their thick woollen uniforms and heavy packs, their feet bloody and blistered in their stiff hobnail boots. On 13 August Joffre received the news he had been waiting for: that the Russian army was preparing to cross Germany’s eastern frontier. Next day, 14 August, the French offensive into Lorraine began too. It involved two armies, Dubail’s First, concentrated around Épinal and Saint-Dié, and de Castelnau’s Second, concentrated around Nancy. Because the Germans had made Metz and its environs a heavily fortified zone, Joffre launched his blow to its south, across the central plateau of Lorraine. Seven army corps, some 300,000 men, arrayed over more than 100 kilometres, would strike north-eastward, broadly from the line of the River Meurthe towards the valley of the River Saar.

At first the French made headway, despite pockets of stiff German resistance and the onset of rain. Bulletins announced feats which borrowed the symbolism of earlier wars, like the capture at Niargoutte farm of a German battle-flag, which some French chasseurs found hidden under a pile of straw after they had driven out the defenders. Success could be measured too in captured towns, where French troops were greeted with cheers, flowers and cigarettes. Dubail’s men on the right captured Sarrebourg, while de Castelnau’s took Château Salins, Dieuze and eventually Morhange, some 20 kilometres inside the German frontier.

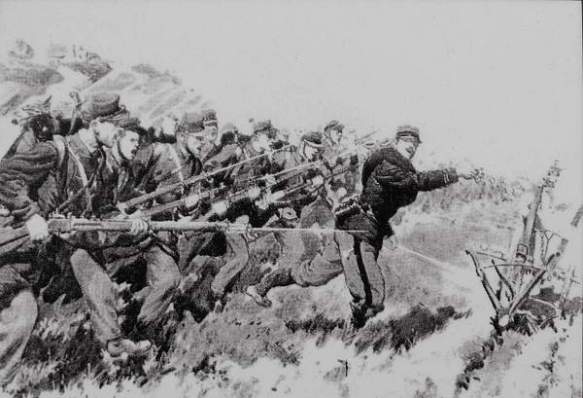

It was as far as the French got. As they renewed their advance on the murky morning of 20 August they were met by a formidable German counteroffensive. The German Sixth Army under Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria (actually directed by his chief of staff, General Krafft von Dellmensingen) was stronger by two corps than Joffre had estimated, and had been conducting a planned withdrawal to a prepared defensive line along the Morhange Ridge. Itching to go over to the offensive, Rupprecht had succeeded in gaining control over Seventh Army to his south, and now overbore the French in a combined assault using massed heavy artillery which outranged the French 75s. The violence of the bombardment was the first large-scale encounter of French troops with the power of German artillery. The horizon seemed to be on fire as thousands of shells inundated French positions. Huge explosions shook the air, throwing up immense clouds of pitch-black smoke and showers of stones and metal fragments, gouging giant craters, sending ancient trees ‘flying through the air like straws in a whirlwind’ and leaving acrid fumes that clawed at the throat. This onslaught was combined with a hail of small-arms and machine-gun fire from swarms of oncoming spiked-helmeted grey-clad infantry. Within hours most of the French Second Army was in headlong retreat, passing back through burning towns it had so recently ‘liberated’. The French dead in their red trousers lay so thickly that when Prince Rupprecht saw the battlefield the next day he thought they looked ‘like a field of poppies’.

Accusations were made subsequently in the French press about the behaviour of the southern troops of 15 Corps who had given way under pressure, leading to another round of sackings. Only Foch’s 20 Corps yielded ground slowly. Soon de Castelnau’s men were back on the French side of the frontier, rallying in time to defend the ridges of the Grand Couronné protecting the city of Nancy. With his left flank thus exposed, Dubail too was compelled to retreat, abandoning Sarrebourg and falling back to his start line.

The failure of the French offensives in Alsace and German Lorraine exposed those inhabitants who had welcomed and aided the French to harsh reprisals – shootings, house-burnings and deportations to Germany. Once German forces followed the retreating French armies over the frontier, the towns and villages of French Lorraine came in for the same treatment that was being meted out to Belgian civilians. No doubt some citizens did join in the defence of their villages, but German reaction to real or suspected acts of civilian resistance was both brutal and disproportionate, and became a mainstay of Entente propaganda.

So imbued were German soldiers with stories of the war of 1870–71 that during their advance they attributed any shot fired at them from an unseen source to ‘treacherous’ civilian francs-tireurs, though in the majority of cases such fire seems to have come either from French rearguards or to have resulted from German ‘friendly fire’. Paranoid about the ubiquitous presence of snipers, nervous German troops entering hostile territory and braced for combat were in no mood to make nice distinctions as to who was guilty. As in 1870, rumours were rife in their ranks that civilians had mutilated German wounded, whether by eye-gouging, throat-slitting, castration or beheading. Reprisals were encouraged and condoned by officers at all levels, who held that such measures would cow resistance and deter insurrection, and were justified by the ‘laws of war’ – or the German version of them, at least, which was at odds with the Hague Convention of 1907 to which Germany was a signatory. Thus after fighting their way into the village of Nomény on 20 August Bavarian troops torched it and massacred fifty-five civilians, including women, children and old people, creating panic in nearby Nancy. Similar incidents occurred at Badonviller on 12 August, where ten civilians died, at Gerbéviller on 24 August where there were sixty victims, and at Lunéville on 25 August where nineteen were killed. Village mayors and priests were commonly taken hostage and, if they were unlucky, were shot on the orders of a junior German officer who wielded the power of life or death over them, as happened at Vexaincourt, Luvigny and Allarmont. German troops pillaged and burned as they went, and at Saint-Dié and elsewhere used civilians as human shields during street-fighting. In all, about 900 French civilians were killed by German soldiers in the opening weeks of the campaign.