The German Third Army, commanded by the Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, had been tasked by Moltke with the invasion of Alsace. It consisted not only of Prussian troops but of the contingents of the South German states. Though Moltke had been impatient for it to advance sooner, it had descended on the French frontier on 4 August. Directly in its path lay the little town of Wissembourg on the River Lauter, where a French infantry division of 6,000 men commanded by General Abel Douay had arrived the previous evening. Douay’s immediate superior, General Ducrot, had been contemptuous of warnings from the town’s civilian authorities of a heavy build-up of German forces north of Wissembourg, dismissing the threat as ‘pure bluff’. Imperial headquarters wired a warning of an imminent attack early on the 4th, but a reconnaissance sent out by Douay failed to find anything suspicious.

The surprise was complete when Bavarian troops came storming across the meadows bordering the Lauter towards the town walls, and volleys of shells started landing on the French positions. Douay’s men fought hard that morning but were forced to retreat as overwhelming numbers of Prussian troops crossed the Lauter to their south and outflanked them. Douay was disembowelled by a shell, one battalion of his men in the town failed to receive the withdrawal order in time and was forced to surrender, while a few hundred men taking refuge in the solid eighteenth-century Château Geissberg on a hill overlooking Wissembourg repelled repeated German assaults until forced to capitulate at around 2 p.m. Their resistance allowed most of the division to get away, less about 2,000 casualties, nearly half of them prisoners. They had inflicted 1,551 casualties on the attacking Germans. There had been no French troops near enough to support Douay. All Ducrot and MacMahon could do was watch smoke rising from Wissembourg from the viewpoint of the Col du Pigeonnier kilometres away. Word spread down other French columns as they toiled along in the heat: ‘You had to have been there to understand the effect of this news. So then, things had begun badly.’

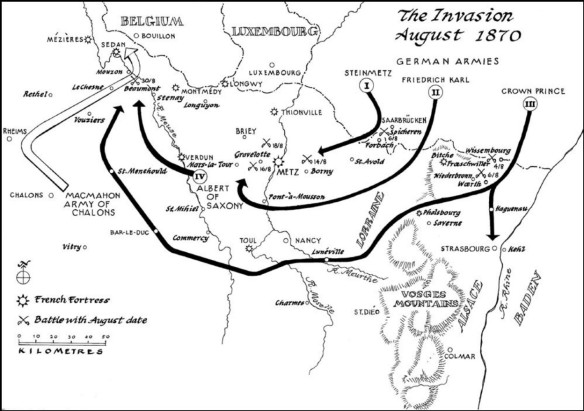

The dispersal of 1 Corps at the moment of the German invasion mirrored the overall strategic situation of French forces in Alsace. Although MacMahon quickly pulled his divisions together and took position on the dominating Frœschwiller ridge, guarding a pass through the Vosges and on the flank of any German advance towards Strasbourg, he was far from any support. Like other French units, 7 Corps, with its headquarters at Belfort in the far south of Alsace, had been bedevilled by supply problems following mobilization and was still incomplete. The emperor had insisted that one of its divisions remain in Lyon to keep order in that republican trouble spot, while another of its brigades was on its way back from Rome. The commander of 7 Corps, Félix Douay (Abel’s brother), had been led to believe – by decoy German troop movements on the far bank of the Rhine – that the main threat to Alsace would come from the east, rather than from the north where it actually materialized. On 5 August Napoleon belatedly put MacMahon in command of all forces in Alsace. The marshal had a reputation as one of France’s most distinguished soldiers, with a record of bravery in Algeria, the Crimea and Italy. The nearest division of 7 Corps was rushed to him by rail, but arrived that evening without its artillery. MacMahon was also given authority over 5 Corps to his north around Bitche and ordered it to join him; but, like other French commanders, General de Failly of 5 Corps was obsessed with the idea that the real threat was on his front, and only belatedly sent one division to MacMahon. It would arrive too late.

Neither MacMahon nor his opponent, the Crown Prince, intended to fight a battle on 6 August, but once the German vanguard made contact with the French along the banks of the little River Sauer fighting began and took on a momentum of its own, sucking in ever more German units whose commanders refused to accept a repulse. On the French left wing, in the woods and clearings north of Frœschwiller, Ducrot’s men beat back the advance of a Bavarian corps. In the centre, in the village of Wœrth and the open pine forest called the Niederwald to its south, the Prussian V Corps was unable to make much headway despite the clear superiority of the German artillery which pounded the French from the hills east of the Sauer. After a morning of furious but inconclusive fighting there was a lull before the decisive phase opened. The Prussian XI Corps crossed the Sauer south of the French position, where the slopes of the Frœschwiller ridge were less steep, and began rolling up the overstretched French line while V Corps renewed its assault, bludgeoning its way into the French centre. MacMahon had accepted battle with 48,000 men, trusting in the strength of his position and the mettle of his troops. These included Zouaves and Turcos of the Army of Africa, who amply confirmed their reputation as the best infantry in the French army, but they were facing over 80,000 Germans. MacMahon, successively throwing in cavalry, artillery and infantry, launched desperate but disjointed counterattacks that failed to stem the German tide for long.

The counterattacks by the French heavy cavalry became legendary in the French memory of the war. The cuirassiers in their steel helmets and breastplates had been little used in the wars of the Second Empire, and had preserved a view of themselves as the elite, battle-winning shock arm. They rejected as heretical any notion that in modern warfare cavalry was best employed in gathering information, harassing the enemy’s communications and preventing his cavalry from observing your own infantry. However, at Frœschwiller they were asked not to rout a weakened enemy, their traditional battlefield role, but to hold back oncoming swarms of German infantry armed with breech-loading rifles. Their orders required them to charge not over open plains but down steep slopes cut by hedges, vines and hoppoles supporting wire trellises – ground that was totally unsuitable for cavalry. There were two distinct cavalry actions, one by Michel’s brigade towards Morsbronn at the southern end of the battlefield at about 1.15 p.m., the other by Bonnemains’ division in the centre, down the slopes towards the outskirts of Wœrth at about 3.30 p.m. Yet in the face of a blizzard of artillery and small arms fire their courage could do no more than interrupt the German advance. When the terminally ill General Duhesme protested, he was told that the sacrifice of his men was necessary to save the army’s right, and he could only exclaim ‘My poor cuirassiers!’ The result bore no resemblance to the kind of warfare these cavalrymen had trained for. An eyewitness described the scene in the road that runs through Morsbronn:

It was there that a great butchery took place. Those unfortunate horsemen, heaped together, confined in a road between banks, were shot at point-blank range by infantrymen posted in the gardens that overlook the lane. There was no combat, not an enemy within a sabre’s length of the cuirassiers: it was a defile swept by missiles. The road was so encumbered with the corpses of horses and men that that evening, after the battle was done, the Prussians were obliged to give up their attempt to march that way with their prisoners.

By mid-afternoon the French had been forced back into a ragged line covering the village of Frœschwiller, targeted by every German gun within range. ‘The Prussians were gaining ground; their artillery was raking our position; Frœschwiller was on fire,’ wrote Major David of 45th Regiment, recording his vain attempts to stem a torrent of fugitives: ‘The battle was lost, so much was evident, and already a mass of troops had deserted the battlefield … The order to retreat was given.’ By 5 p.m. the French had disappeared towards Niederbronn and the mountain gap along a forest road littered with the dead and dying, leaving every building around crammed with wounded who were tended by a handful of doctors. For the next three days the surgeons performed operations from sunrise to sunset. One of them remembered that ‘Some of the wounded dragged themselves up to us in order to advance their turn. One of them cried out “People queue here. It’s just like at the theatre!” And laughter took hold of all those desperate fellows. Men will laugh, even in Hell.’

Frœschwiller had been a bigger and bloodier battle than Spicheren. The Germans had bought victory at a cost of 10,642 casualties, while French losses approximated 21,000, including 9,200 taken prisoner and 4,188 men who found their way to Strasbourg, which the Germans soon laid under siege. Meanwhile, peasants from the ruined villages on the battlefield were compelled to toil for days at digging burial pits in weather that had turned dismally cold and wet.

The double defeats of 6 August produced a ‘veritable panic’, an ‘indescribable disorder’, when they became known at imperial headquarters next day. About a quarter of the army had been directly involved in the defeats, but the psychological effect on the French high command magnified their impact. Over the course of the next week the ailing emperor changed his mind repeatedly about what strategy to adopt. His first thought was that the whole army should fall back and concentrate at Châlons Camp, though that meant giving up much of eastern France without further contest. Other options were only fleetingly considered; for instance either falling back to the south-west so as to stay on the flank of the German advance, or concentrating southwards against the Crown Prince’s Third Army as it emerged into Lorraine through the Vosges passes in pursuit of MacMahon. The fact that for two or three days after their victories the Germans largely lost contact with the French army and were in the dark regarding its movements would have favoured such a move. But Napoleon thought only of barring the direct road to Paris. Briefly, on 10 August, it was decided to make a stand on a branch of the River Nied, 15 kilometres east of Metz, with the four corps immediately available, Ladmirault’s 4th, Bazaine’s 3rd, Frossard’s 2nd and the Imperial Guard. However, the position was quickly deemed to be insecure, and next day the army fell back to Metz ‘by that sort of passive attraction that fortresses exercise over irresolute commanders’.

The indecision of the high command communicated itself to the troops, who could not understand why they were marching away from the frontier and the enemy. Marches were badly organized, with men having to stand in ranks fully laden for hours on end while waiting their turn to join a column. The appearance of German cavalrymen too often caused French generals to assume mistakenly that enemy infantry must be close behind, and prompted unnecessary night marches in a week of awful weather. On reaching camp, wrote a lieutenant in 4 Corps, ‘the men, soaked to the skin, unable to put up their miserable little tents on ground that had become nothing but a sea of mud nor light fires to cook dinner, unable even to eat their ration bread that had turned to pulp in their haversacks, their faces drawn and their clothes filthy, seemed ready to drop from exhaustion’. Things were worse for the men in the defeated 1 and 2 Corps, many of whom had lost all their equipment in the aftermath of battle. Increasingly soldiers resorted to begging and pillage. The cavalry meanwhile provided very little information and seemed to expect to be protected by the infantry rather than vice-versa. The high command kept it in the lee of the marching columns instead of between them and the enemy.

By taking command Napoleon had hoped to garner the laurels of victory, but now he bore the obloquy of defeats that came as an enormous shock to French opinion. The empress recalled the Legislature, which met on 9 August amid large demonstrations by supporters of the republican opposition, who demanded greater parliamentary power and the recall of the incompetent emperor to Paris. Inside the Chamber Ollivier, the butt of public contempt, was swept from power by a vote of no confidence. The motion was proposed by the Bonapartist Right, the very men who had clamoured loudest for war and who exploited their opportunity to eject the despised liberal ministry. Eugénie replaced Ollivier with the Count de Palikao, an old cavalry general who had led the French expedition to China in 1860. The new ministry took a series of measures to raise more men and money to fight the war, and to prepare Paris for a state of siege: steps that would have seemed unthinkable three weeks earlier. The cabinet did not want Napoleon to return to Paris, which would be an admission of defeat, but saw the necessity of appeasing popular feeling by appointing a new commander-in-chief and chief of staff, for Le Bœuf was blamed as much as Ollivier for the war’s disastrous beginning.

In the army too, Napoleon’s lack of strategic grasp caused him and Frossard to be blamed for defeat. In Paris and among the troops Marshal Achille Bazaine was the popular favourite because he had risen through the ranks and was known to have been out of favour at court after his command of the army in Mexico. Since 5 August Bazaine had nominally had authority over Frossard and Ladmirault as well as his own corps, but had seemed diffident about exercising it because Napoleon and Le Bœuf had continued to issue direct orders to them regardless of the new arrangement. At the urging of the empress, on 12 August Napoleon reluctantly acquiesced, appointing Bazaine commander-in-chief, while a devastated Le Bœuf stepped down as chief of staff. ‘We are both sacked,’ Napoleon told him. On that day German cavalry entered Nancy, the chief city of Lorraine, meeting no resistance.

Defeat had sapped the emperor’s authority and prestige, ushered in a new cabinet and commander-in-chief, and also deepened France’s diplomatic isolation.