The British army was now reorganized on a more ordered footing, with provision for raising 175,000 regulars, 52,000 militia – some 16,000 of them in Ireland – ‘fencible’ (volunteer) cavalry and 34,000 hired mercenaries. A new campaign was planned, involving two pincers to close in on Paris. An army would be landed near Le Havre and move up the Seine; another would advance from the north-east: this would consist of some 300,000 men, 40,000 of them British and German soldiers which would advance from Flanders and seize the frontier fortresses.

It was the old plan again, under the old commander, the twenty-nine-year-old Duke of York whom both Pitt and Dundas privately considered incompetent, but were unable to replace: the Austrians actually preferred him because they believed they could manipulate him. The Prussians, who were to provide 100,000 men, insisted that because the war was being waged entirely in British interests they be paid £2 million. The British were understandably reluctant to pay. So too were the Austrians, who were by now deeply suspicious of their Prussian rivals. Not until April was agreement reached for a reduced Prussian force of 62,400 men at a cost of around £1 million paid largely by the British.

All now seemed well: the King of Prussia, no less, decided to command his army; the Emperor of Austria also took command of his forces, arriving in Belgium to inspect the allied armies on 9 April. This brought to an end an unseemly squabble in which the Duke of York, who had refused to serve under the Austrians’ best general, General Clairfait, because of his inferior status, agreed to serve under the Emperor. As was remarked at the time: ‘one incompetent prince, who knew little about war, was thus to be commanded by another incompetent prince who knew nothing.’

Just ten days later, however, a large Polish uprising under the popular Thaddeus Kosciusko, which had broken out the previous month, moved on to capture Warsaw. This aroused intense anxiety among Britain’s continental allies: the Russians wanted help to quell it; the Austrians were alarmed at the destabilization of central Europe; and the Prussians wanted to share in any possible spoils. But for the moment the campaign against France proceeded. The fortress of Landrecies was taken, partly by a brilliant British cavalry charge. It became a classic in British military history. On 24 April, two squadrons of British and two of Austrian cavalry, numbering 400 men, had come across a body of 800 French cavalry in thick woods near Montrecourt. They pursued the larger French force up a hill, where they found themselves face to face with an entire division. The British promptly charged forward, while the Austrians engaged in a flanking movement. They were taking on sixty cannon, aiming straight at them, supported by 12,000 men, ranged in six battalions. The charge of the 15th Hussars was memorably described by a young cornet, Robert Wilson:

When we began to trot, the French cavalry made a movement to right and left from the centre, and at the same moment we saw in lieu of them, as if created by magic, an equal line of infantry, with a considerable artillery in advance, which opened a furious cannonade with grape, while the musketry poured its volleys. The surprise was great and the moment most critical; but happily the heads kept their direction, and the heels were duly applied to the ‘Charge!’ which order was hailed with repeated huzzas . . .

The guns were quickly taken; but we then found that the chaussée, which ran through a hollow with steep banks, lay between them and the infantry. There was, however, no hesitation; every horse was true to his master, and the chaussée was passed in uninterrupted impetuous career. It was then, as we gained the crest, that the infantry poured its volley – but in vain. In vain also the first ranks kneeled and presented a steady line of bayonets. The impulse was too rapid, and the body attacking too solid, for any infantry power formed in line to oppose, although the ranks were three deep. Even the horses struck mortally at the brow of the bank had sufficient momentum to plunge upon the enemy in their fall, and assist the destruction of his defence . . .

The French cavalry, having gained the flanks of their infantry, endeavoured to take up a position in its rear. Our squadrons, still on the gallop, closed to fill up the gaps which the French fire and bayonets had occasioned, and proceeded to the attack on the French cavalry, which, though it had suffered from the fire of part of its own infantry, seemed resolved to await the onset; but their discipline or their courage failed, and our horses’ heads drove on them just as they were on the half-turn to retire.

A dreadful massacre followed. In a chase of four miles, twelve hundred horsemen were cut down, of which about five hundred were Black Hussars. One farrier of the 15th alone killed twenty-two men. The French were so panic-stricken that they scarcely made any resistance, notwithstanding that our numbers were so few in comparison with the party engaged, that every individual pursuer found himself in the midst of a flock of foes.

As the British and Austrians pursued the French, they came across a baggage train carrying fifty more guns and fell upon this, spiking the guns. The pursuit continued for six miles, leaving 1,200 French casualties in its wake. There had been a couple of other considerable feats of British arms – at Vicogne, when the Coldstream Guards had crossed a narrow bridge in the face of French guns and overrun the French position, and at Lincelles when they overcame a heavily manned French redoubt – but this was the first really superb feat of arms.

The British and Austrian army now plunged on into France. Wilson again captured the intensity of the fighting at Mouveaux:

The cry of ‘Charge to the right!’ ran down the column, and in the same moment we were all at full speed. The enemy redoubled his efforts, and struck at us with his bayonets fixed at the end of his muskets, as we wheeled round the dreaded and dreadful corner, already almost choked with the fallen horses and men which had perished in the attempt to pass. My little mare received here a bayonet-wound in the croup, and a musket-ball through the crest of her neck. Two balls lodged in my cloak-case behind the saddle, and another carried away part of my sash. Our surgeon and his horse were killed close at my side, and a dozen of my detachment fell at that spot under the enemy’s fire. We still urged on, ventre à terre, pursued by bullets.

Suddenly, before the least notice could be given, the whole column of cavalry was arrested in its career, and at the same moment, of course, recoiled several yards. The confusion, the conflict for preservation, the destruction which ensued, baffles all description. Three-fourths of the horses, at one and the same moment, were thrown down with their riders under them or entangled by the bodies of others. The battling of the horses to recover themselves, the exclamations of all sorts which resounded through the air, accompanied by the volleys of the triumphing enemy, presented a picture d’enfer which, as one of the French then firing upon us, and afterwards taken, told me, even made his own and his comrades’ hair stand on end . . . It was not till I got over the ditch that I saw the cause of our calamity. Fifty-six pieces of cannon with their tumbrels, etc, stood immovable in the road, the drivers having cut away the traces and escaped with the horses when they found the enemy’s fire surrounding them. Such was the consequence of sending out as drivers the refuse of our gaols – for that was the practice of the day.

Never, never could a column be more completely surrounded and by five times its numbers; never did a body of men so circumstanced escape with such a comparatively small loss. At Pontachin a column of 1,800 French had endeavoured to force its way through some orchards. When the mass was wedged in one of them which had a very small outlet, the Austrians had opened a battery of twelve guns – 12-pounders – upon it, and with such remarkable razing precision and effect, that I myself counted 280 headless bodies. Such a beheading carnage was perhaps never paralleled.

The British and Austrians were now over-extended, partially cut off in the rear and under fire on both sides. On 8 May, the French counter-attacked at Turcoine. The British were forced to fight a rearguard action, while the Austrians remained strangely passive. The British lost nineteen guns out of twenty-eight, while eighteen Austrian battalions failed to support them. Craig, the Duke of York’s adjutant-general, fulminated: ‘We never saw an Austrian but by two and threes turning away. I am every day more and more convinced that they have not an officer among them.’ The allies regrouped to resist the French charges at Tournai and on the Sambre.

The King of Prussia chose this moment not to join his forces in the west but in the east, on the Polish front. The Austrians, concluding pessimistically that western Flanders was lost, went on the defensive, and the Emperor decided to return to Vienna at the end of May. The Prussians now refused to do the bidding of the British, and the Austrians seemed all but out of the fight, falling back along all their lines.

On 26 June Moira landed at Ostend with some 7,000 reinforcements and marched to Ghent: one of his officers was Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Wellesley, a novice in war. The Duke of York meanwhile wrote angrily to Prince Coburg that ‘we are betrayed and sold to the enemy’ by the retreating Austrians. The French crossed the Sambre again, this time under General Jourdan, with reinforcements of 70,000 men, the army of Sambre-et-Meuse, the Republic’s best. They thrust between the British-Dutch forces and the Austrians to the east.

The British believed the Emperor of Austria had sold out. In fact he had left because he recognized that his brother, the Archduke Charles, was a far more gifted commander – although he suffered from epilepsy which would incapacitate him at critical moments. He was ably supported by his chief of staff, General Mack von Lieberich. But it is true that the Austrians had no great enthusiasm for the war and had long sought to disembarrass themselves of the troublesome burden of governing their far-flung Netherlands possessions.

Jourdan turned his entire army against the Austrians and they met on the battlefield of Fleurus on 26 June. The Austrians fought furiously and inflicted enormous losses on the French. The battle lasted the whole day – ‘fifteen hours of the most desperate fighting I ever saw in my life’, as a young officer, Soult, was later to remember, having had five horses shot from beneath him. Another soon to be famous young French officer, Bernadotte, fought beside him.

Archduke Charles boldly suggested a cavalry counter-attack to go behind the French and break their lines. But the Austrian commander, Coburg, ordered a retreat as dusk settled to a ridge called Mont St Jean above the village of Waterloo. The allied armies now fell apart, going their separate ways – the British towards Antwerp, the Dutch across the Cheldyt, and the Austrians towards the Rhine.

Brussels fell on 11 July, and Antwerp later in the month. Holland’s very survival was now at stake. Nieuport fell to the French and hundreds were butchered. The Austrians were now in full flight towards the Rhine. Cologne fell in October as Jourdan’s army pushed forward.

Thoroughly alarmed, Pitt, whose government had now been reinforced by the Whig faction represented by the Duke of Portland, sent two emissaries to Vienna to seek stronger Austrian support – Thomas Grenville, brother of the foreign secretary and one of the men who had brokered the end of the American War of Independence, and Lord Spencer. They were to be completely disappointed, finding in Vienna only ‘weakness and inefficiency’ and ‘total want of vigour’.

The Austrians soon surrendered two more fortresses, Valenciennes and Condé, while demanding a subsidy of £3 million from the British for continuing the war in 1794 and a similar figure for the following year. Pitt meanwhile cut off his subsidy to the even more reluctant Prussia, which retaliated by seeking a peace treaty with France.

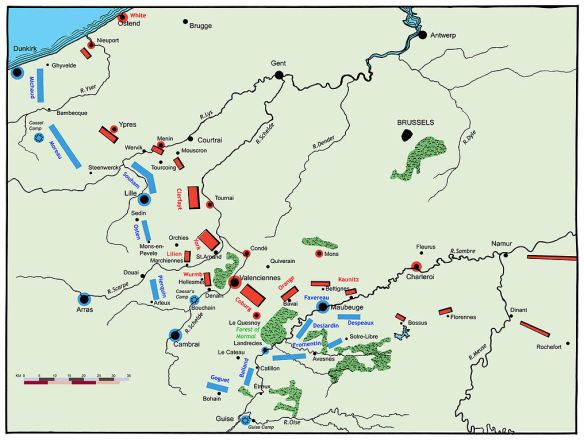

Positions of the armies at the start of the 1794 campaign.

Faced by collapse in the Low Countries, Pitt cast desperately about, and thought he had found an ally to champion in Joseph, Comte de Puisaye, leader of the Breton resistance, who implored him for 10,000 British troops in support. But both Dundas and Moira were firmly opposed to such an ‘adventure’. Pitt sought to reinforce the French émigré army along the Rhine under the Prince de Condé. In addition, with the bloody fall of Robespierre, he sought solace in the hope of a royalist coup and peace talks to be spearheaded by a wily British envoy and effective leader of the British secret service in France, William Wickham.

Meanwhile the French invaded Holland, taking Sluys and Eindhoven and reaching Cologne. They paused only when they reached the river Waal. Pitt’s talk of ‘embarrassment’ was now replaced by fears of a ‘calamity’. The ineffectual Duke of York was recalled, along with seven regiments, leaving the British troops under the command of General Harcourt. The Dutch began to consider surrender. The British were ‘hated and more dreaded than the enemy, even by the well-disposed inhabitants’.

As ice formed on the rivers, the French pressed forward across the Waal, until checked by a British and German counter-attack. At the village of Boxtel, the twenty-five-year-old Arthur Wellesley ordered his men to open their lines to allow the fleeing soldiery through, then closed his line as the French galloped forward in pursuit. He waited until they were almost upon him before giving the order to fire and, as the foremost assailants fell, the rest turned round and fled.

The situation was desperate. Supplies of transport, medical equipment – such as it was – and clothing had all broken down, although food was still plentiful. General Craig reported that the army was ‘despised by our enemies, without discipline, confidence or exertions among ourselves . . . every disgrace and misfortune is to be expected’.

William Wilberforce proposed talks with France. Pitt angrily rejected this in December. Holland, however, fell to the French the following month and the principal British ally, the Stadtholder, fled to England. Amsterdam was taken on 19 January 1795, and a few days later the French cavalry galloped across the Zuyder Zee to seize the Dutch fleet, imprisoned in the ice. The British continued to retreat in a desperate shambles while the Dutch sued for peace and the French in February impounded British ships in Dutch ports.

The same month Pitt decided to withdraw the remains of the army from the continent: by April the infantry and part of the artillery were embarked at Bremen, leaving only the cavalry, some of the gunners, the Hanoverians, and what remained of the Austrians attached to the British forces. An eyewitness described the wretched British evacuation: ‘There were few who had not lost a limb; many had lost both legs and arms; numbers of them were reduced to mere skeletons.’

It had been one of the worst defeats in British military history, with casualties even higher than the previous year, around 20,000 or two thirds of the entire British expeditionary army. The French imposed strict terms on the Dutch, including taking Maastricht, part of southern Holland, and the area around Flushing. The Dutch navy and part of its army were conscripted to the war against Britain. By the end of the terrible year of 1794 it seemed game, set and match to the French: they had won twenty-seven pitched battles, killed 80,000 and taken as many prisoners. They had conquered Flanders, made Holland a puppet, crossed the Rhine, subdued the Vendée and retaken Toulon. The return of these wretched men across the Channel in defeat was a truly black day for British arms.

The Prussians now signed a peace treaty with France at Basle, and by the middle of 1795 the conclusion was inescapable that Britain’s prosecution of the continental war against revolutionary France had been an utter disaster. The French had twice repulsed large combined allied armies attacking from the north, the second time crushing Holland and forcing the British to evacuate under pitiable and ignominious circumstances. France had stood alone against most of Europe, and magnificently repulsed its enemies.

After the glories of the previous century, Britain’s reputation as a military power on land had descended to an all-time low: the shambles in Toulon and in Holland now eclipsed memories of the triumphs of Clive in India and Wolfe in Quebec. The British policy of trying to get its continental allies to do most of the fighting through bribery was neither very glorious nor very successful. The Hessians and the Hanoverians had proved indifferent troops; the Prussians had haggled and then deserted when the British had been unwilling to be browbeaten; and huge offers of subsidy had not yet persuaded the Austrians to take the offensive. With the Low Countries effectively in enemy hands, and Spain now lost, the only friendly country now left to Britain west of Corsica, Sardinia and parts of Italy was little Portugal.