Central administration had broken down. Local landowners were reluctant to take high office because of the cost. There was no longer a pride in being part of the governing structure. The expelling of Roman administrators during Constantine’s reign in Gaul meant that the network of central authority had been rejected and men with experience of high office were lacking. Few men wished to take up office because of the cost and the responsibility. This meant that local arrangements had to be made, differing from place to place. The fact that Honorius sent letters to the cities of Britain, ordering them to take measures on their own behalf, was merely a form of words; he assumed the cities were still in existence and well-managed but he had no knowledge that was the case.

It might be argued that Britain, lacking official contact with central Roman authority, began to break into its tribal areas. Tribal disputes may explain the appearance of linear earthwork defences. The Wansdyke could be explained as a frontier between the Durotriges and the Dobunni. Bokerley Dyke would have separated the Durotriges from an advance by the Belgae or vice versa. The Fleam Dyke, with a probable date of AD 350–510, marked the boundary of the borders of the Catuvellauni and the Iceni, and Beecham Dyke and the Foss Dyke also protected the Iceni in the fen area. Grim’s Dyke, north of London, would have protected the capital from attacks from the north. These might be expected to protect areas from attacks by the Saxons.

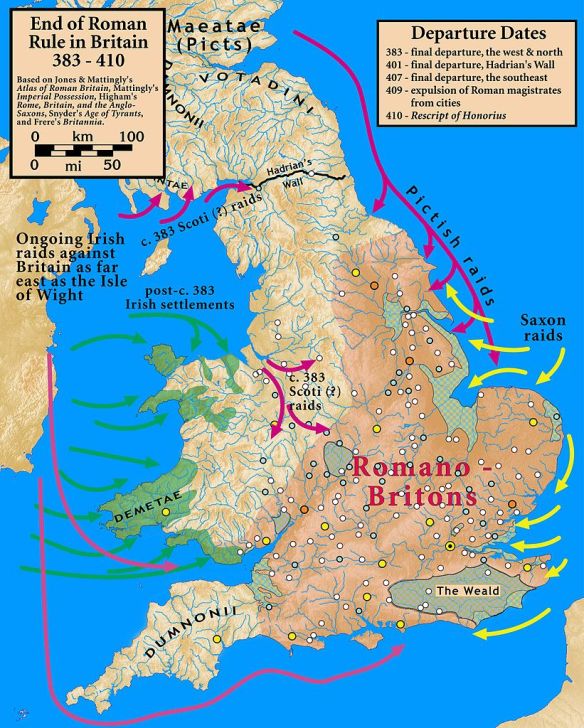

There were, however, other problems. Raids by the Picts and the Scots were becoming far more frequent. They came first as raiders and then as settlers. The Britons were forced to seek help from the Saxons against the Picts and the Irish, and the earliest Saxon settlements may have been at the invitation of the Britons to give protection. Traditionally the date of the arrival of the first Saxons, as given by Bede, basing his work on Gildas, is AD 449. Archaeological evidence has proved that settlement had occurred well before that date. A group of Saxon settlements south of London may have been linked with a group placed there to guard the city.

Possibly these raids and settlements forced the Britons to make one last attempt to get the central Roman power to supply aid. Gildas said that a message was sent to Agitius, consul for the third time, ‘in the following terms, “to Agitius come the groans of the Britons … the barbarians drive us to the sea; the sea drives us back to the barbarians; between these two we are either slaughtered or drowned.” Yet for all these pleas no help was forthcoming.’ This can be dated to AD 446 and refers to Aetius, who was then the leading military man in the army of Rome. He was credited with defeating Attila and his Huns in AD 451, only to be stupidly murdered by the Emperor Valentinian in AD 454, who thus lost control over his army.

Britain also had new rulers. Gildas mentioned a proud tyrant, whom Bede identified as Vortigern, a Celtic name meaning ‘High King’. Nennius, in his History of the Britons, also mentioned him and he may have been born about AD 360 and died in the late AD 430s. Nennius said that the Saxons, under their leader Hengist, came to Britain as exiles and that they were welcomed by Vortigern, who allowed them to settle on the Island of Thanet in return for military assistance.

Unfortunately an agreement that they should be paid and fed broke down. In addition, Vortigern fell in love with Hengist’s daughter, married her and gave the district of Kent to Hengist as a bride price. Whatever the truth, Vortigern seems to have been unable to prevent the Saxons from landing. Forty boatloads were mentioned and more arrivals meant that the Saxons soon spread across the land.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle confirms this story, stating that Vortigern (Wurtgern) invited Hengist and Horsa and their warrior bands to Britain to provide protection again warrior bands roaming the country. It may be argued that Hengist and Horsa are not the actual names; as nicknames they both indicate ‘horse’.

Whatever the case, the Chronicle said that they accepted this invitation but then set up their own kingdom in Kent holding the area by defeating the Britons at battles at Aylesford (AD 455), where Horsa was killed, and at Crayford (AD 456).

They apparently came as foederati, indicating that they had obligations with subsequent rewards to guard Britain. Gildas said that they were given generous amounts of food but complained that these rations were not enough, saying that if they were not increased they would break the treaty. Soon they took up their threats with actions.

From then on Saxon penetration of the island seemed inevitable. Gildas mentioned the arrival of Aelle in AD 477, who founded the kingdom of Sussex, defeating the Britons at the Battle of Anderida (Pevensey) in AD 491. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that in AD 495 Cerdic and Cynric landed in the West Country and founded the kingdom of Wessex. These accounts of the invasions are very speculative, especially as the Chronicle stated that landings were in two or three ships. It would have been impossible for such few men in these ships to win decisive battles. Nevertheless, they indicate some folk memory and it would be futile to deny that the country soon succumbed to Saxon invasion and settlement.

Some Saxon settlements have been found as far inland as Dorchester-on-Thames. Possibly these were founded by men hired as foederati.

One name that emerges from the history of this time is Ambrosius Aurelianus, also called Arthus. Little is known of this man and his history has become irrecoverably entwined with medieval legend and romance so that it is difficult to untangle fact from fiction. As King Arthur, he was immortalized by Sir Thomas Malory in the fifteenth century in his work Le Morte d’Arthur, with an elaborate account of Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, thus intermingling fact and fiction. The historical Ambrosius was a warrior, probably trained in Roman military tactics, who led mounted bands of Britons against the Saxons. The Historia Brittonium called Arthus Dux Bellorum, reminiscent of a Roman military title. He was associated with twelve battles and probably led mounted horsemen, well trained, who could easily rout a force of foot soldiers. Eight of these battles took place at fords where foot soldiers would be at a disadvantage. These victories culminated in a last great battle, about AD 500, at Mount Badon (Mons Badonicus), an unidentified site but probably somewhere in the south-west. Gildas said that ‘after this there was peace’ and about AD 540 spoke of ‘our present security’.

An illustration depicting the battle of Mt. Badon in which the historic Arthur (if there actually was one) was said to have won a major victory over the encroaching Saxons. If Arthur was a real person, I think this depiction is a lot closer to what he may have looked like. He would likely have been a Romanized Briton with Celtic heritage but Roman training.

This, however, was merely a respite because soon the Saxon conquest was renewed. By AD 600 most of Britain had been divided into Saxon kingdoms. The Saxons did not attempt to emulate Roman customs and institutions, and it would appear that the Britons had not so assimilated Roman institutions that they wished them to continue. The Anglo-Saxons imposed their own law, language, political systems and material values on Britain. Roman Britain, whose official contact with the Roman Empire had ended about AD 410, merged irrecoverably into Saxon England.