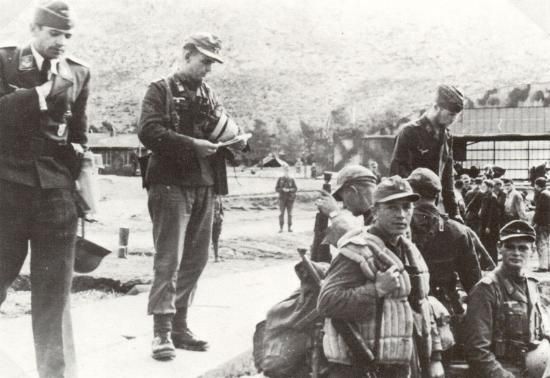

Brandenburgers in Leros 1943

Brandenburg units were also used extensively in Hitler’s invasion of Russia in 1941. Their tasks were made much easier by the fact that Finland had sold Germany scores of tanks, trucks, uniforms and greatcoats captured during its war with Russia in 1939–40. The German high command had listed a hundred separate targets along the Russian frontier which Brandenburg special soldiers could be tasked to take by any means. This would prepare the way for the mass of German armoured and infantry divisions, which could once again employ the same Blitzkrieg tactics as had proved so successful against the western allies. By capturing key airfields, bridges and road junctions, the Brandenburg detachments would allow the Panzer divisions to roll into Russia that much faster.

Being equipped with Russian military vehicles and uniforms made it easier for the Brandenburgers to operate behind the enemy lines. No questions were asked as they went about their clandestine missions inside Russian territory. Indeed the success of the German invasion of Russia was due in large measure to the myriad of missions the Brandenburgers had carried it in those crucial first few days of the offensive.

But there would be further tasks in quite different theatres of war for the Brandenburg units. One such area was North Africa, although no one in the German high command believed this was an ideal location for their particular skills. A German army under the great General Erwin Rommel had been sent to North Africa to support the broken Italian forces, which had been all but crushed by the British army under General Wavell. So fast had been Wavell’s advance against the Italians that most of Mussolini’s so-called African Empire was on the verge of defeat. Rommel saw that what was needed was men with knowledge of Africa from families who had lived and worked in the German possessions in East and South West Africa; Germans who could speak Arabic, Swahili and English and who understood the African way of life. Volunteers were invited to join the Brandenburgers’ new Afrika Kompanie and within weeks sixty former émigrés had been selected and trained. Rommel wanted the Afrika Kompanie to work behind British lines, reporting back by wireless on the location, size and equipment of the British forces they came across.

Small groups from the Afrika Kompanie carried out such operations in the desert, but because most of them were unable to speak English without a distinct German accent, much of the information they gathered was not particularly crucial or even accurate.

However, in 1942 Rommel believed he was on the verge of crushing the British Eighth Army, and he planned, after achieving this, to drive on through Egypt to the Nile and grab the vital link, the Suez Canal. For this campaign he would need skilful Special Forces men. Rommel called the Brandenburg commanders and outlined the tasks he would want the Afrika Kompanie to carry out. Their first task would be to seize the bridges over the Nile and the Suez Canal to prevent their destruction by the British, and then to hold them until Rommel’s Panzer divisions could break through and join up with the Brandenburgers. It was a tough mission but one which never materialised, for General Montgomery would rally his troops, defeat Rommel and his Panzers in the critical battle of El Alamein and then, some three months later, smash the German defences and drive them out of North Africa.

But now, as he faced Montgomery’s Eighth Army, Rommel gave the Afrika Kompanie a new, vitally important but extraordinary task – to locate and trace the route the British were using to supply reinforcements to Montgomery. He had been informed by German Intelligence that the British were landing tanks, guns, small arms, ammunition, spares and other equipment in Nigeria and transporting them across some fifteen hundred miles of rough terrain, as well as the Sahara Desert, to Cairo. Rommel charged the Afrika Kompanie with the task of determining the exact route of this supply line so that it could be harried by German forces and cut.

First, the Afrika Kompanie needed to acquire British vehicles, uniforms and weapons so that any British troops they came across would believe they were members of the British Long Range Desert Group. Most of the route would pass through countries friendly to Britain, so it was necessary for the Germans to portray themselves as British. The Afrika Kompanie also acquired a British Spitfire, which they would use as a long-distance reconnaissance plane as Brandenburgers on the ground made their way from Egypt to Nigeria. The Spitfire, with Royal Air Force markings, would fly several hundred kilometres ahead of the group, circle and return to the Brandenburgers. It was hoped that the aircraft might come across British reinforcements making their way to Cairo and return to the group each day with vital information on such troop movements.

The Afrika Kompanie left Libya with twelve fifteen-hundredweight trucks, twelve half-tracks fitted with two-pounder guns, four jeeps carrying anti-aircraft machine-guns, a staff car, a wireless vehicle, a petrol tanker, a workshop vehicle and a rations vehicle. The column travelled due south to Al Qatrun, some two hundred kilometres from the border with Niger, the country between Libya and Nigeria, and set up their headquarters, which included a communications base and a rough airstrip for the Spitfire. They also left at Al Qatrun two half-tracks equipped with machine guns in case of attack from Arab brigands. They waited four days for the all-important Spitfire to arrive but to no avail. It never turned up, which meant the Afrika Kompanie now had a much more hazardous and difficult task. Apparently, the German aero engineers were unable to get the captured aircraft into the air.

One small group of Afrika Kompanie soldiers drove west from Al Qatrun into Algeria to carry out a recce of the French colony in case supplies for Montgomery’s army were being brought through southern Algeria. Another group drove south-east to the Tibesti mountains in northern Chad. A third group, the largest, would search for supply lines in southern Algeria’s Tassili mountain range, some six hundred kilometres in length and reaching more than fifteen hundred metres in places.

If any of the three groups failed to discover the Allied supply route, their orders were to continue the search, criss-crossing the arid, desolate wastes of the Sahara desert on foot and in the searing heat of summer. All that they managed to discover was that French forces controlled the two mountain ranges. They had found no supply routes and no evidence of one having existed. Rommel was not impressed. The mission was remarkable, however, because it showed the extraordinary resilience, tenacity and adaptability to exceptional circumstances that tough, well-trained Special Forces could display in the most inhospitable terrain.

The final mission of the Brandenburgers in World War Two was a gallant, heroic battle fought with extraordinary courage despite the utter futility of the orders they had been given. The manner in which those men carried out the orders was a magnificent example of bravery, a quality which has continued to characterise special soldiers to the present day.

At the end of March 1945 the 600 Brandenburg Paratroop Battalion was put into the German bridgehead on the eastern bank of the River Oder at Zehdenick, sixty kilometres north of Berlin. For three exhausting weeks the Brandenburgers managed to hold their positions against massed Russian attacks, despite the fact that battalions to the left and right of them had been overrun and destroyed. But, running low of ammunition, the 600 Battalion took a terrible battering and when they finally withdrew there were only thirty-six of the original eight hundred men still alive.

The survivors were reinforced by a few hundred trainees who had been rushed from Berlin in a desperate last effort to push back the Russian advance. Some wounded Brandenburgers rejoined their unit from their hospital beds, so strong was their commitment to their unit. Then the 600 Battalion was ordered to pull back to Neuruppin, some fifty kilometres to the west, and to defend the town to the last man. At dawn on April 3 1945 a single company of eighty-four Brandenburgers was facing two Russian tank divisions and two infantry divisions. It was an extraordinarily gallant defence by Special Forces soldiers under the most extreme battle conditions. The battle raged for eight hours as the Russians sent in wave after wave of tanks, backed up by hundreds of infantry.

After four hours the Germans had used up all their rocket-propelled weapons. In the final hours of this extraordinary battle the thirty surviving Brandenburgers had only hand grenades and satchel charges to hold back more than a hundred T34 and JS tanks. They still had some ammunition for their machine guns and personal weapons to keep the Russian infantry battalions at bay, but even that they had to fire sparingly.

When all their anti-tank rockets had been used, the Brandenburgers adopted a new tactic. They would wait in ditches until the first Russian tanks had passed by and some would then scramble out and on to the rear decks of the vehicles, dropping grenades into the open hatch to blast the crew. Others would run alongside the tanks, planting magnetic, hollow-charge grenades with a nine-second fuse on the sides. Having done this, the soldier would dive back into the ditch to escape the blast before moving on to the next tank.

Sometimes the Brandenburgers would wedge plate-shaped Teller mines between the tank’s tracks and running wheels. These exploded with tremendous force, blowing the tank track apart and rendering the vehicle useless. Some soldiers stopped the advancing tanks instantly by simply flinging their satchel charges under the tracks. Within two hours more than sixty Russian tanks were at a standstill, wrecked by the audacious Brandenburgers.

Five separate assaults were launched by the Russian commanders and five times they were repulsed by the tiny band of men who were taking enormous risks, putting their lives on the line during every enemy assault. Because only some thirty Brandenburgers were alive after the fourth assault, they took up defensive positions only and used only machine guns, sub-machine guns and rifles. The Russian infantry had stopped trying to advance behind the protection of their tanks because they were being mowed down by the Brandenburgers. They let the tanks take the brunt of the German gunfire and waited for the inevitable victory.

Although they knew they were staring death in the face, the Brandenburgers held their ground and their nerve. Somehow they managed to stop the fifth tank assault, and the Russian crews leapt from their tanks and scrambled back to safety as bullets zipped around them. But such a one-sided battle could not last much longer. The sixth tank attack, at dusk, finally overran the German position and, ironically, it was at the very moment of defeat that the Brandenburgers’ commander was given the order by radio to withdraw.

He had only about twenty men left. There were no wounded to take back. As the tiny band struggled away from the area in the darkness, they left behind the hulks of dozens of blazing or burnt-out Russian tanks. It was the final battle of World War Two for the German Special Forces. They had been utterly defeated, but in their defeat their remarkable courage could only be saluted.