Dancing with Bears-The Berlin Airlift – Set during the Berlin airlift this scene captures the harassment of the Soviet planes as Allied cargo comes in on a constant schedule. By Brian Bateman.

Moscow reacted to the failure of the London foreign ministers’ meeting by calling into question Western rights in Berlin. The Soviet-licensed Berlin daily, Tägliche Rundschau, ran an editorial on December 19 arguing that quadripartite control of Berlin made sense only as long as Germany remained under four-power rule. After Clay and Robertson announced plans to give the Bizonal Economic Council limited political power, a second, stronger editorial appeared, reiterating the link between moves toward a west German government and a Western presence in Berlin. The newspaper claimed the West had created a west German state and thereby “nullified” Western rights in Berlin, which was part of the Russian zone.

Western officials shrugged off the editorials as crude threats. In late January, Bevin proposed a meeting of the three Western powers and the Benelux countries to discuss the future of the western zones. The Russians were pointedly excluded from this London conference, which ran from February 25 to March 5, recessed, and reconvened from April 20 to June 2. It proved to be “the most important conference on the future of Germany since the end of the war,” for it brought the French, British, and Americans together in a common program. The communiqué issued when the conference recessed on March 5 announced agreement on west German participation in the Marshall Plan, a federal form of government, and coordination of the economic policies of the French zone with those of the Bizone. This cluster of initiatives came to be known as the “London program.”

The Russians regarded the conference as a threat to the Soviet state, not just to their interests in Germany. The Western powers were bent on German political, economic, and military revival and a separate west German government; something had to be done to deter them from this dangerous course. Stalin expressed his displeasure in several ways, including harassment of Western traffic to Berlin, steps toward an east German regime, and diplomatic maneuvering. The Soviets tried a variety of measures, and as each failed, they saw no choice but to escalate.

Soviet inspectors boarded a U.S. military train at Marienborn on January 6 and demanded to check the papers of German passengers; Russian liaison officers at Clay’s headquarters were persuaded to recall the inspectors after a thirty-five-minute standoff. On January 12, the day after the second Tägliche Rundschau editorial, Russian officials began requiring Soviet countersignatures on interzonal consignments out of the western sectors. On January 15, they prohibited German vehicles from entering the Soviet zone from west Berlin; drivers were instructed to pass through the Russian sector and obtain a special pass first. Soviets stopped a British passenger train en route to Hamburg on January 23, demanding to inspect two cars filled with Germans. When British officials refused, the Russians held the train at Marienborn for nearly eleven hours before detaching the two cars, sending them back to Berlin, and letting the rest of the train proceed. Two nights later, they stopped another train; this time, the British allowed them aboard. After the Soviets were satisfied that all the Germans had valid interzonal passes, they allowed the train to continue westward.

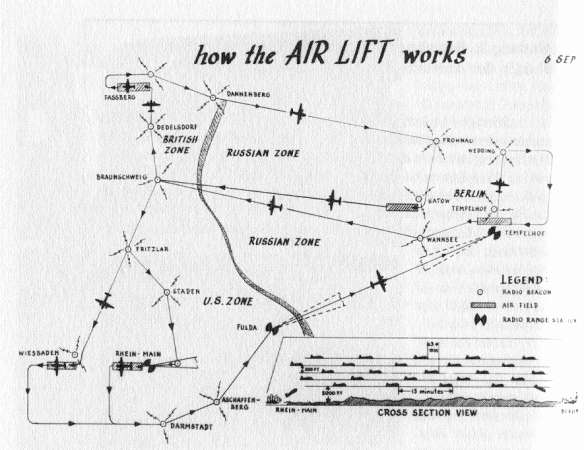

Americans noted “ever increasing” efforts to curb air travel in January. At a meeting of the Berlin Air Safety Center in February, the Soviet controller proposed changes in the regulations governing the corridors and the Berlin Control Zone. He also wanted civil aircraft to obtain in advance Soviet permission to use what he described as the “air corridors of the Soviet Zone of Occupation.”

On March 9, four days after the London session adjourned, Moscow called Sokolovsky and his political adviser, Vladimir S. Semenov, home for consultations. They and their superiors decided to impose an escalating series of restrictions on Western traffic to and from Berlin in order to compel the Western powers to abandon the London program or leave Berlin. Stalin seemed to prefer the latter course in discussions with SED leaders on March 26. Predicting defeat for his party in city elections scheduled for the autumn, Wilhelm Pieck told Stalin that he and his colleagues “would be glad if the [Western] Allies left Berlin,” prompting Stalin to reply, “Let’s try with all our might, and maybe we’ll drive them out.”

One can read too much into these words. They do not necessarily include a willingness to use force to expel the Western powers. A better approach was to harass them until they left of their own accord. Furthermore, Stalin’s words suggest that he had not thought carefully about his goals. As compatible as they appeared at first glance, they were at odds. In one tactic, Berlin was to function as a hostage: in exchange for the city’s safety, the West would drop the London program. Yet if Pieck had his wish and Berlin came under Soviet control—if the hostage died—Moscow would lose leverage over the London program. The paradox that local success might undermine overall Soviet goals would plague Kremlin diplomacy throughout the coming crisis.

Stalin’s efforts to derail the London program went beyond the harassment of Western transit. He also took steps toward establishing an east German regime, paralleling Anglo-American initiatives in the Bizone. On February 13, Tägliche Rundschau announced that Sokolovsky had given the economic commission of the eastern zone powers comparable to those just given to the Bizone’s economic council. A more ominous move followed a month later, when the Soviets began establishing so-called People’s Police. Organized and equipped more as military formations than as police, these units gave the SED a private army.

In diplomacy, the Soviets sought to reassert Moscow’s voice in German affairs. A single theme united Russian protests over the Bizone and the London conference: these Western actions involved questions that only all four occupying powers could decide. The West, the Soviets contended, was usurping the prerogatives of the ACC and circumventing the Soviet Union. Stalin had accepted the EAC protocols and the Potsdam agreements because they gave him a veto over Germany’s future; he was not about to surrender it.

Stalin chose to remind the Western powers of the ACC’s value—and the link between it and the continued Western presence in Berlin—by putting the ACC in jeopardy. The break came on March 20. No council meeting had been scheduled, but Sokolovsky suddenly exercised his right as chairman that month to call one. He opened the meeting by demanding full information about the London conference. After Robertson and Clay avoided giving direct answers, Sokolovsky read a long prepared statement denouncing the conference. The Western powers, he concluded, had proved that the ACC “virtually no longer exists as the supreme body of authority in Germany.” He declared the meeting adjourned and marched out of the room, his delegation at his heels.

Sokolovsky also began carrying out the instructions he had received in Moscow. Russian troops mobilized and moved to the zonal border on maneuvers. The Soviet-licensed press began to carry stories that “subversive and terrorist elements,” bandits, and criminals were taking advantage of lax transit regulations to disturb the tranquility of the eastern zone. To stop such outrages, the Soviets announced on March 30 that “supplementary regulations” covering Western travel to and from Berlin would take effect April 1. Berlin had taken center stage in the East-West conflict.

#

The Pentagon’s first impulse was to evacuate. Army Lieutenant General Albert C. Wedemeyer, director of the Plans and Operations Division, asked his staff to find out how many transport planes Clay had, how many passengers they could carry in an emergency, and how many Americans were in Berlin. Staffers at air force headquarters drafted a message to the commander of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), Lieutenant General Curtis E. LeMay, offering armed bombers to move supplies and people in and out of Berlin. Asked whether the United States could use atomic weapons if the crisis escalated, Brigadier General Kenneth Nichols, head of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, said no; the only qualified assembly teams were on a Pacific atoll for weapons tests.

Truman’s minimal role deserves comment. In one sense, it was not unusual. Truman had taken little interest in the occupation since Potsdam, and that hands-off style continued after the London Council of Foreign Ministers. Marshall made commitments at Prince’s Gate on his own. Although Truman stayed informed about developments, he ratified policy; he did not make it. Forrestal discussed the crisis with him by telephone, and Royall sent him Dratvin’s letter, Clay’s proposed reply, and the transcript of the teleconference with Clay. Truman’s preference was to avoid a public role: no consultations with Congress and no public statement. Yet his stance was odd in at least two respects. First, he considered the situation serious—“as serious,” he told the Canadian prime minister, “as in 1939”—and his notion of a leader’s responsibilities during a crisis did not include inaction. Second, his behavior was inconsistent with the famous Clifford-Rowe memo on election strategy, which called on the president to rally voters by asserting leadership in foreign affairs.

Bradley and Wedemeyer were in the communications center again at 10:00 P.M. Berlin time on March 31 (4:00 P.M. in Washington). They were ready to approve the reply to Dratvin, subject to a final question: hadn’t Soviet officials walked through Western trains as recently as September? It was an important point. If Russians had routinely boarded Western trains in the past, how could Clay’s soldiers shoot them now?

Washington’s preoccupation with the risk of war—the unintended consequence of his own efforts to dramatize events—infuriated Clay. He mustered all his eloquence for one last plea.

Legalistic argument no longer has meaning. We are now faced with a realistic and not a legalistic problem. Our reply will not be misunderstood by 42 million Germans and perhaps 200 million Western Europeans. We must say . . . “this far you may go and no further.” There is no middle ground which is not appeasement. . . . Please understand we are not carrying a chip on our shoulder and will shoot only for self-protection. We do not believe we will have to do so. We feel the integrity of our trains as a part of our sovereignty is a symbol of our position in Germany and Europe.

When this appeal failed to sway Bradley, Clay was ready to drop the whole business. Bradley approved the reply with minor changes, only to have Clay snap that the reply was unimportant. “Our subsequent action is all that concerns me,” he declared. He was so angry that he said he may have erred in referring the crisis to Washington: “I am not too sure I was right in ever bringing it up,” he told Bradley in disgust. Bradley ignored this outburst and authorized Clay to move trains, as long as they did not carry additional guards or additional weapons. Guards were to prevent Soviets from boarding, but they could not shoot first. Even after Bradley pointed out that the president had approved these instructions, Clay complained. His soldiers would obey, but the orders were unfair “to a man whose life may be in danger.”