FOCKE-WULF FW-190D-9 “Red 1” Heinz Wimmersaal Sachsenberg The inscription on his Fw 190 D9 was “Verkaaft’s mei Gwand I foahr in Himmel!” meaning “Sell my clothes I’m going to heaven”

JV-44 flew its first full combat mission on April 5, 1945, and it started with a vengeance when five Me 262s lifted off from their new base at Munich-Riem, where they shot down a B-17 near Karlsruhe outright by Lützow, another B-17 claimed by Klaus Neumann, and two B-24s claimed (actually written off, damaged beyond being salvaged) also by Neumann and Heinz Bär, with another two claimed also by Bär and Fährmann. The records show that the 379th Bomb Group lost three B-24s, and the 388th and 453rd Bomb Groups also lost one bomber each.

One eyewitness account of this mission, and confirmation of three B-24s going down in rapid succession, is the statement by 1st Lt. Charles M. Bachman, a B-24 pilot in the 379th Bomb Group: “I was not flying with my own crew on this mission to central Germany. I was an instructor with a new crew who had no previous combat experience. We called this the ‘Dollar Mission’ for the new crews. I was in charge of their B-24 Liberator as First Pilot. We flew bucket lead on this mission, and were well into German airspace when a fighter suddenly went past our aircraft from the rear, very fast. [Author’s note: This must have been Klaus Neumann’s jet, as he was the first to engage].

“‘What the hell was that?’ my co-pilot exclaimed. ‘Messerschmitt 262,’ I replied. ‘Jet fighter.’ Three B-24s went down in the first seconds of the attack and could never have known what hit them. Gunners reported another flight of jets coming in; where the hell were our escorts? I felt my aircraft shake as our gunners opened fire, and the stench of cordite filled the cockpit.

“One jet passed only feet above our heads as the guns rattled out [JG-7 fighters more than likely, as they engaged following the JV-44 attack]. The jet got smaller by the second to our front, leaving us as if we were standing still in the air. This jet suddenly exploded and disintegrated in front of the formation. Our upper gunner later reported that he had raked the jet’s belly with his guns as it overshot us and was later given credit for destroying it. The formation lost two more B-24s from the second wave of jets. Almost fifty of our airmen lost their lives that day.” This fighter that exploded was definitely a JG-7 machine, one of the two they lost that day.

The 401st Bomb Group also lost a B-17 when a jet closed in fast, fired a burst, and then raced away, chased by Capt. John C. Fahringer. He closed, saw good strikes, and the jet slowed down. As they both emerged from the clouds, Fahringer scored the kill and the pilot bailed out. Who this pilot was is unknown, and he was reported as missing. However, the offending jet was also from JG-7, since the only two jets lost that day were from that unit, as JV-44 did not lose any planes or pilots.

April 7 was also a busy day for the jet pilots, but in contrast to Foreman and Harvey, who state that “it is believed that aircraft of JV-44, equipped with R4M rockets, made an attack upon Fortresses over Thuringia, several being shot down.” The record according to the interviews conducted with German pilots and the Luftwaffekriegstagebuch show that no claims of destruction or damaged aircraft were made by JV-44 pilots. The only units making solid claims were JG-7 and KG-54 (see Appendix 14), for a total of nine aircraft claimed: five B-17s, one B-24, a P-38, and two P-51s. One of the P-38s (F-5 Recon) of the 30th Recon Squadron, Ninth Air Force, was shot down by Oberleutnant Walter Schuck of III./JG-7. The pilot, Capt. William T. Heily, bailed out and spent eight days as a prisoner of war until he was liberated by American forces.

April 8 was to prove to be the litmus test for JV-44, as the RAF threw a formation of Lancasters against Hamburg. JG-7 was also heavily involved. JV-44 encountered P-38s, as Steinhoff, Krupinski, and Fährmann saw them pass by underneath. Steinhoff made his dive, chasing the fighters, until he decided better:

“I learned a long time ago that chasing the American fighters without having your own top cover was suicide, and I know that many of our pilots, becoming enthusiastic anticipating the easy kill, were jumped by high flying fighters. I radioed to my guys not to follow, and then I told them to follow me, as ground control had located a bomber formation. We were carrying rockets, and bombers were what we wanted. We did not have much flight time left, so a quick hit and run and we were gone. I think Krupinski had already turned back being low on fuel.

“We saw them below and closed in a diving pass as the escort fighters sort of broke all over the place. I lined up my aiming point and fired the rockets. Nothing happened! But I was going too fast to use the guns, so I blew right through the formation. I pulled up and banked and then was in a good firing position. I looked but did not see Fährmann. I learned later that he had been shot down. I saw a bomber trailing black smoke while another was drifting away, also smoking, so they must have been his victims. I then locked onto a B-17 and fired, and he was going down without question. I then headed back, and when I landed learned that Fährmann was safe, he had bailed out and was unhurt, just shaken up a bit.”

April 9 was uneventful while April 10 did not see much air combat, although JV-44 was strafed by the 353rd Fighter Group, losing three jets on the ground, while JG-7 lost twenty-seven jets in combat either destroyed or damaged. The only success for JV-44 on April 12 was a B-26 shot down by Heinz Bär, and the unit suffered no losses. April 13 was a down day, as were the next two days for Galland’s group. April 16 was rather busy, as Galland took to the air in combat for the first time. Galland recalled his first enemy contact flying the Me 262, leading his group of heroes in a last-ditch effort to salvage their pride and honor when their world was crumbling around them: “During my first [successful] attack with rockets, Krupinski was on my left wing, and we witnessed the power in these rockets. I remember that I shot down two Martin B-26 Marauders.”

Krupinski recalled this mission: “Galland flew into the bombers, but nothing seemed to happen. Galland, who was leading our flight flew past the formation without firing, but he turned around and then fired his salvo of rockets at a group of B-26 bombers. In moments, one disintegrated and another was falling—the tail had been blown away, and both parts were fluttering down through the light clouds. I fired my rockets and had some near hits, and damaged a couple of the bombers, but the smoke from Galland’s two kills obscured the sky in front of me. Seeing the result of those rockets hit was incredible, a fantastic sight really.

“After this attack we flew off a few hundred yards so as not to hit any debris or get jumped by enemy fighters, and then attacked again using our four thirty-millimeter cannons. I damaged a couple of bombers but scored no kills that day and Galland had the only confirmed victories. I had a rocket misfire myself, and only a few of my rockets fired and did not do their job well. Galland pulled around and fired again. Later he admitted that he had failed to take the safety off the rockets, and he did not even think about using his cannons.

“On the second approach was when he had fired, and during that mission he brought down two bombers. I lined one up, and then fired my cannons on the second pass. I heard some thumps and hits in my jet, but nothing major. I could not believe just how effective those rockets could be. It was like firing a shotgun into a flock of geese, really. Galland had some .50-caliber bullets that struck his fighter and it had to go in for repair after we landed.”

April 17 saw Galland again lead his band of nine jets on a mission to intercept heavy bombers in conjunction with I./KG-54, and the intercept was made just after the bombing run, as the B-17s were turning away from the flak zone. Steinhoff recalled the mission:

“I was with the boys two thousand meters above, just waiting for the bombers to exit the flak zone. I did not like flying through my own flak, because it was very accurate. Galland then gave the order to attack, so we dived in. It seemed that many of the B-17s were smoking, damaged, probably from the flak, and perhaps the other fighters. I fired my rockets, but again nothing happened, so I fired the guns into two bombers and saw some hits but nothing destroyed, and no one else had any success. Then I saw one of our jets shaking and then go into a skid and collide into a B-17. The jet’s wing cut the bomber’s tail section off, like a knife, and both planes fell to earth. I saw no parachutes from either aircraft. Krupinski said it was his wingman, Schallmoser. We all thought that he had been killed for certain. Well, I thought that we had really screwed up that mission. It just shows that we still had things to learn.”

The German tactic was to hit the bomber formations like wolves on a flock of sheep, like a prizefighter delivering a stunning blow before following up with the knockout punch. Some pilots came in too close when attacking, allowing the closing speed to get away from them. Galland gave his perspective regarding Schallmoser, who suffered from this problem during several air battles:

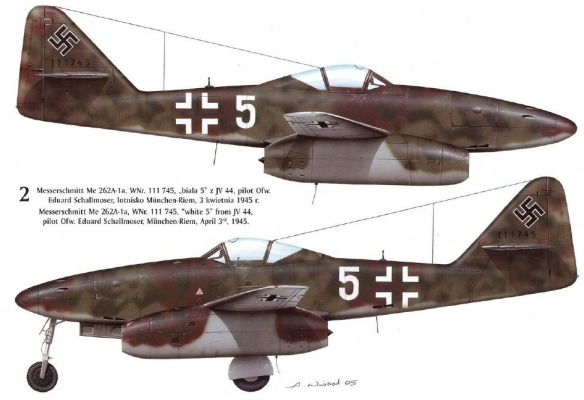

“I saw [Unteroffizier] Schallmoser, who was famous for ramming enemy fighters, fly past me, his ‘White 5’ too close for comfort, and I led the group head-on. As a result of my ignorance my rockets did not fire, but I poured thirty-millimeter cannon shells into one bomber, which blew up in spectacular fashion and then fell in flames, and I flew right through the formation, hitting another. I could not tell if that bomber was finished off, so I banked around for another run; all the while my jet was receiving numerous hits from the bombers’ defensive fire.”

Klaus Neumann also recalled the mission: “Yes, I remember that day. Schallmoser actually flew right over me, and we were all firing at a bomber each, my rockets fired and I saw some hits but nothing really great. Then Schallmoser rolled just slightly left, and then he crashed into this bomber. I looked up and broke right hard to avoid being hit by either aircraft. I also broke the rule, I instinctively pushed the throttle as far as it would go, but it was already all the way forward. I just missed being hit by the tail section of this B-17. If that had hit me I would have been killed for sure. I thought for sure that Schallmoser was gone.”

Schallmoser had been hit with a solid stream of .50-caliber fire that shot out both engines and shattered his canopy. He lost control and hit the B-17. The gunner who shot him down was Technical Sergeant Murdock K. List of the 305th Bomb Group. He had shot Schallmoser up, and when he lost control he flew past List’s bomber and crashed into the next one in the box formation. The crew and its pilot, 1st Lt. Brainard H. Harris, all perished. No one managed to bail out, as confirmed by Steinhoff.

Schallmoser was pinned in the wreckage, the force of the impact and g forces holding him in as it spun out of control, minus the right wing, and he kept pushing until he was sucked out into the subzero cold. As he left the aircraft his head struck the side of the fuselage, rendering him unconscious. Falling until he became conscious, he then pulled the ripcord, and landed in a field not far from a road, where he flagged down a car and was given a ride to a police station.

Hans “Specker” Grünberg, who ended the war with the Knight’s Cross and eighty-two enemy aircraft in 550 missions, with five victories in the jet, was also on this mission, and provided his own perspective: “I saw Schallmoser streak toward the bombers. He always did that, we all did, but we always fired, pulled away and then considered another attack. The ‘Rammer’ was not of this mindset. I think that he simply became tunnel visioned, too focused, wanting the kill at all costs. He probably believed his own propaganda, where he used to say, ‘I can’t be killed; I am too pretty.’

“We would always laugh at him. But when I saw this plane break apart after the collision, I also, like everyone else, knew he was dead. How he survived that crash, and all the others, still puzzles me. They say that God protects drunks and fools. The Rammer was both, so I guess he had a good insurance policy.”

Neumann describes the reappearance of Schallmoser: “He showed up, with a bandage on his head, and his arm in a sling. He had dislocated his left shoulder. Someone said that his new nickname was ‘The Ghost’ because he came back from the dead. Oberst Lützow said, ‘No, he is the Rammer,’ and the name stuck with him. You know that he flew the next day? Incredible.”