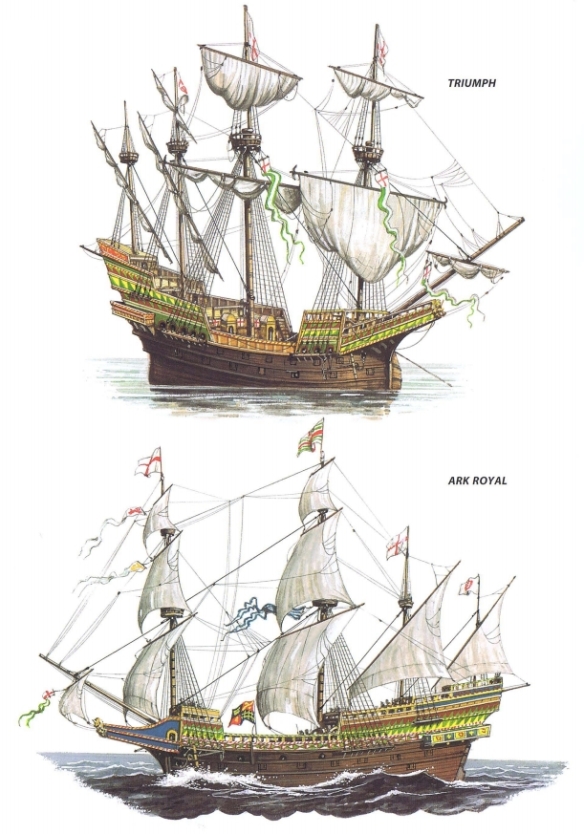

TRIUMPH AND ARK ROYAL, 1592

The aim of this plate is to highlight the differences between two of the most powerful ships in the Elizabethan Navy Royal. The Triumph was a galleon of 740 tons, built in 1561 according to the requirements of the time. In many respects she resembled her Spanish counterparts, which is hardly surprising as her lines were probably based on the trio of galleons commissioned by Mary I, based upon the warships used by her husband, Prince Philip of Spain. However, the Triumph boasted a powerful armament of 46 heavy guns, mounted on modern carriages. This meant she could outshoot any vessel in the Spanish Armada. During the 1588 campaign, she served as the flagship of Sir John Hawkins. By contrast, the 550-ton Ark Royal was build in 1587 according to the race-built galleon design advocated by Hawkins, and represented the latest word in Elizabethan ship design at the time of the Spanish Armada. Although her armament of 38 heavy guns made her less powerful than the Triumph, her speed and manoeuvrability more than compensated for any lack of hitting power. During the Armada campaign she served as the fleet flagship.

Specifications – Triumph Displacement: 741 tons Keel length: 100ft (305m) Beam: 40ft (12.2m) Armament: 46 guns Crew: 340 sailors, 40 gunners, 120 soldiers Service notes: Built 1561. Rebuilt 1596. Condemned, 1618

Specifications – Ark Royal Displacement: 550 tons Keel length: 100ft (30.5m) Beam: 37ft (113m) Armament: 38 guns Crew: 268 sailors, 32 gunners, 100 soldiers Service notes: Built 1587. Rebuilt 1608. Wrecked off Tilbury, 1636

In 1595 Newport sailed Golden Dragon to the Mediterranean on a trading voyage in consort with a number of other merchantmen and had a share in two Spanish prizes taken on the return. In October his status changed when he married into the Glanfield family, who were leading London goldsmiths. All his subsequent voyages were in command of Neptune, newly built for a partnership between Newport and his in-laws, initially with the participation of Ridlesden and Michael Geare, another experienced corsair captain. Neptune is variously described as ‘powerful’, ‘formidable’ and too big for inshore work, so she was probably in the 300-400 ton range.

Geare was given command of the pinnace built to accompany Neptune, but during the first voyage, in 1596, he failed to meet Newport at the agreed rendezvous and made an independent and lucrative voyage while the bigger ship returned empty-handed. Newport and the Glanfields blamed Geare for this and sued him for cheating them of their shares of his prizes. Sailing solely for himself and his in-laws, Newport’s next voyage to the West Indies in 1598 was so quickly profitable that they were able to send Neptune out again later that year, accompanied by the pinnace Triton.

Newport fell ill and the voyage was successfully conducted by Neptune’s master, who returned with a good prize but had to sue Newport and the Glanfields not only for his share as acting captain but for the recovery of personal property they had retained and for expenses they had authorized. The Glanfields appear to have been the worst offenders in sharp practice, but from the revealing depositions in Andrews’ English Privateering Voyages to the West Indies it’s apparent that there was no trust among the London corsair promoters, or between them and their employees. The big winner was the Lord Admiral, for whom the High Court of Admiralty was a nice little earner, while the judges graciously accepted gifts from plaintiffs and defendants alike, their consciences no doubt assuaged by the thought that their even-handed venality balanced the scales of justice.

Newport did not sail again until 1599-1600, when he made a rapid voyage to capture and sack Tabasco, not far from Campeche on the Gulf of Mexico, returning with everything removable, including the church bells. In his voyage of 1601-02 he took several modest prizes near Havana, but in 1602-03 he was rumoured to have captured five fragatas loaded with gold, variously reported as worth one or two million pesos. There is no record of any such haul being brought back to England, or any significant improvement in Newport’s lifestyle, so the rumour is best seen as an indication of Newport’s reputation as an outstandingly able and lucky captain.

After the peace treaty he sailed to the West Indies with trade goods, returning in 1605 with two crocodiles and a wild boar for the royal zoo, which he presented to the king in person. In 1606 he was chosen to command the Virginia Company’s first expedition. Sailing in Susan Constant (120), followed by Godspeed (40) and the fly-boat Discovery (20), he left London in late December, spent a month waiting in the Downs for a favourable wind, then sailed to Chesapeake Bay via the Canary Islands and the West Indies, arriving in late April 1607. Newport made four more voyages and played a crucial role in the development of the Jamestown settlement.

During the 1609 crossing in the newly (and badly) built Sea Venture (300 tons burden), carrying a new governor and 150 settlers, Newport was ordered to take a more direct route and, with the ship foundering after surviving a hurricane, ran her aground on Bermuda. The party spent the winter on the island, cannibalizing the wreck to build two boats in which they sailed to Jamestown. The epic voyage inspired Shakespeare’s last sole-authored play, The Tempest, and resulted in Bermuda becoming a self-governing colony in 1620, three years before the first English settlement in the Caribbean, on St Kitts.

Newport made his last voyage to Virginia in 1611, and closed his remarkable career in the service of the East India Company, making three journeys to Java during the last of which, in 1617, he died. The following year saw Sir Walter Ralegh’s life ended by the executioner’s axe after a Spanish settlement on the Orinoco River was sacked during his venture to find El Dorado in Guiana. When preparing the expedition, he discussed the possibility of capturing the silver fleet with Attorney General Sir Francis Bacon. Ralegh replied to Bacon’s warning that it would be piracy by asking if he had ever heard ‘of men being pirates for millions?’

Perhaps not; but for a man who failed to return with millions at a time when the English and Spanish courts were discussing the dynastic marriage of the future King Charles I and the Infanta María, the outcome was certain. He had been under sentence of death for treason since 1603 and the sentence was carried out on 29 October 1618. In his long valedictory speech from the scaffold he rejected the charges that had brought him there, but confessed to having been ‘a man full of all vanity’ who had lived ‘a sinful life, in all sinful callings, having been a soldier, a captain, a sea-captain and a courtier, which are all places of wickedness and vice’. Indeed – but it was the vanity that killed him.

As to wickedness and vice, he was a babe in arms by comparison with the men who ingratiated themselves with the new king at his expense: Sir Robert Cecil, made Earl of Salisbury in 1605, and the Howards. Lord Admiral Charles was made Earl of Nottingham in 1597, but Lords Henry and Thomas were made Earls of Northampton and Suffolk by James in 1603, before his coronation. Under the new regime their corruption became unconstrained and the Royal Navy went into abject decline; but the seeds of that decline had been planted and nurtured during the last years of Elizabeth’s reign.

There were many reasons for this, the most important being the unreformed royal finances. Elizabeth never felt strong enough to risk offending the Protestant gentry who were the mainstay of her regime by modernizing the inadequate, medieval tax structure she inherited. The same consideration inhibited her from clamping down on piracy and the result was the perilous symbiosis of public and private interests in the corsair war, stripped of all pretence and deniability after 1585, and which became a full-scale guerrilla war after the 1588 Armada.

In the following three years more than three hundred prizes were taken with a declared total value of £400,000. It’s reasonable to assume the true value was more than twice as much, and the attrition continued at the rate of about £100,000 in declared value every year through the 1590s. Only a small proportion of this came from the spectacular expeditions we have reviewed, and as we have seen the benefit to the English exchequer was in no way commensurate with the damage done to the enemy’s economy and shipping – for every prize thought worth bringing back to England at least another was scuttled or burned.

There was also the multiplier effect of causing Spanish and Portuguese ships to set out on oceanic voyages at the wrong time of year. The English captured only three of the great Portuguese East India carracks and caused the captains of another two to burn them to escape capture – but they often forced the rest to sail out of season, increasing their exposure to bad weather. After Philip became king of Portugal the rate of attrition due to natural causes went from one in ten to one in four. The Portuguese merchant fleet was also whittled down by incessant attacks on ships sailing between Brazil and Lisbon with raw sugar and hides, which were taken in such numbers that leather and sugar became cheaper in England than in Iberia.

The effect on Spanish and Portuguese shipping was devastating. From being by some distance the premier oceanic powers even before the union of the two crowns in 1582, they were progressively driven to conducting much of their trade in neutral ships. Thanks to Philip II’s insistence that the rebel Dutch were still his subjects and thus free to trade with the rest of his European empire, they occupied the commercial space left when English merchants were shut out of Iberia, and also benefited from the increase in third-party carrying trade brought about by English attrition of the Spanish and Portuguese merchant fleets.

The paradox infuriated the English traders, and laid the foundations for the Anglo-Dutch wars of the next century. Early in 1598, before Philip III declared an embargo on trade with the Dutch Republic, the well-connected gentleman John Chamberlain, whose letters shed priceless light on the period, reported that many in London no longer judged it in their interest to support the Dutch:

One of the chiefest reasons I can hear for it is a kind of disdain and envy at our neighbours’ well-being, in that we, for their sake and defence entering into the war, and being barred from all commerce and intercourse of merchandise, they in the meantime thrust us out of all traffic, to our utter undoing (if in time it be not looked into), and their own advancement, and though the fear of the Spaniards recovering those countries [the Netherlands] and increasing greatness do somewhat trouble us, yet it is thought but a weak policy for fear of future and uncertain danger (which many accidents may divert) to endure a present and certain loss.

It is impossible to say whether Philip III’s reversal of his father’s policy prevented a breach in the Anglo-Dutch alliance, but it certainly removed a growing source of friction. Even so, as more and more enemy goods were shipped in neutral hulls, the political cost of the corsair war increased.

From about 1597 the volume of complaints from the Hanseatic League, Sweden, Denmark and the Italian states about indiscriminate English predation began to rise steeply. Following the Franco-Spanish Peace of Vervins in May 1598 English attacks on French ships also increased, but the official French response was muted by common strategic concerns and the fact that Henri IV owed Elizabeth a great deal of money. Not so the German and Baltic states, which began to retaliate against English trade. Long before peace was declared the English merchant community had come to see that a prolongation of the war harmed their interests.

Why, then, did it persist? Mainly because the Spanish insultingly over-played their hand at a conference in Boulogne in 1600, but also because, although the Dutch and French feared she might, Elizabeth would not renege on her commitment to the Dutch Republic. Nor would it have been wise to seem forced to make peace because of the Irish rebellion, even though it was eating into her exchequer more than the rest of her military expenses put together. Consequently the tempo of the self-financing corsair war increased and with it, inevitably, the number of offences against neutrals.

Although correlation is not causation, it is suggestive that indiscriminate attacks increased during the last year of Lord Burghley’s life. His had always been a voice arguing for moderation in the queen’s council, and he had avoided personal involvement in the corsair war. His son, Secretary of State Sir Robert Cecil, was not so scrupulous, and he was now politically joined at the hip with Lord Admiral Howard, now Earl of Nottingham, who had much to gain from an indiscriminate corsair war.

Not content with his tenth of the loot declared by others, Nottingham also sent out corsair ships of his own, which he equipped and perhaps also supplied at the queen’s expense, particularly after the death of John Hawkins and his replacement as Treasurer of the Navy by the poet and dramatist Fulke Greville, who knew nothing of ships and the sea. But Howard also made money from the increase in the number of petitions flooding into the High Court of Admiralty and by issuing back-dated letters of reprisal even to notorious pirates. His rationale was that they would otherwise move to Munster or Barbary, which tells us all we need to know about the ethics of the noble earl.

One must assume that his parasitism earned him the secret contempt of the seafaring community, but ironically it strengthened England’s negotiating position during the London peace conference of May-August 1604, slightly off-setting the urgent desire for peace signalled by James I, who agreed a ceasefire from 24 April 1603 with the emissaries sent by Philip III and the Archduke and Archduchess of Austria, co-rulers of the Spanish Netherlands, to congratulate him on his accession.

Several corsairing expeditions took place nonetheless, at least one of them to the Mediterranean promoted by Nottingham with Cecil as a silent partner. When the Venetian ambassador complained that claims lodged with the High Court of Admiralty were being ignored, the king swore, ‘By God, I will hang the pirates with my own hands, and my Lord Admiral as well’.

The five-man English delegation included Cecil, Nottingham and Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton. The two delegates not clearly identified with the Cecil-Howard interest were the victor of Kildare, Lord Mountjoy, created Earl of Devonshire by James in 1603, and the ailing Lord Treasurer Thomas Sackville, created Earl of Dorset in March 1604. Remarkably, the opening words of the Treaty of London implicitly identified the person of Queen Elizabeth as the casus belli:

Know all and every one, that after a long and most cruel ravage of wars, by which Christendom has for many years been miserably afflicted, God (who has the disposal of all things) looking down from on high, and pitying the calamities of his people (for whom He was pleased to shed His own blood, that He might bring them peace, and leave it with them) has powerfully extinguished the raging flame by a firm confederacy of the most potent princes of the Christian world, and graciously made the day of peace and tranquillity shine, which was hitherto rather wished for than hoped for by the grace of the omnipotent God, the kingdoms of England and Ireland devolving, for extirpating the seeds of discord, upon the most serene prince, James King of Scotland, and consequently those causes of dissension removed, which so long fomented and nourished war between the predecessors of the most serene princes Philip the III King of Spain, and Albert and Isabella Clara Eugenia Archduke and Archduchess of Austria, Duke and Duchess of Burgundy, &c. and of the said King James.

Despite the best efforts of Cecil and the Howards, all they could achieve in the matter of trade with the Indies was a declaration restoring the status quo ante bellum, which left the issue unaddressed. In effect the informal understanding was the same as that reached by the negotiators of the 1559 Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis between Philip II and Henri II of France: neither party would permit any action by their subjects ‘beyond the lines’ to compromise the peace. Although the English undertook to support Spanish efforts to uphold their own laws, that was a dead letter for as long as the Earl of Nottingham was Lord High Admiral – which he remained until his death in 1624.

Although the Treaty of London rejected Spanish demands that the cautionary ports be handed over to the Archduke and Archduchess on grounds that James was bound by the terms of the 1585 Treaty of Nonsuch, he did undertake to give no more aid of any kind to Holland and Zeeland, and:

He promises on the word of a King, to enter into a new treaty with the said States, in which treaty his Majesty shall assign them a competent time wherein they may receive just and equal Conditions of Pacification from the said most serene Princes, his dearest Brother and Sister, otherwise, if they shall refuse to do this, the most serene King of England, thereby freed from former Conventions and Agreements, shall appoint and ordain what he shall judge honourable and just concerning these towns – and his said most dear Brother and Sister shall be given to understand, that he will not be wanting to perform the offices of a Prince who is a Friend.

Out of context, the terms agreed in 1604 were those that Philip II sought before the 1588 Armada. The difference was that the Dutch were now more than strong enough to continue the war unaided. In April 1609, two years after the battle of Gibraltar in which the Dutch Navy destroyed a Spanish fleet at sea – something the Royal Navy had never managed – the Twelve Years’ Truce agreed by the rulers of Spain and the Southern Netherlands amounted to de facto recognition of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch finally recovered the cautionary towns in 1616, when James was so desperate for money that he accepted £100,000 down and £150,000 in three half-yearly payments to settle outstanding Elizabethan loans totalling £600,000.

In sum, the Treaty of London called off the officially sponsored corsair war that had become an expensive embarrassment for England, and peace was declared because both sides were financially exhausted. As such it represented an admission of strategic defeat by Spain without representing a commensurate victory for England, which saw the fruits of victory plucked by the Dutch not merely in continental Europe but in the Baltic, the Mediterranean, the East and West Indies and even in the North Sea.

They were able to do this because in the midst of a conflict that threatened them far more than it ever did England, they put commerce ahead of all considerations apart from those directly threatening their independence. Beginning with the sack of 1575, the centuries-old commercial expertise of Antwerp transferred to Amsterdam. Under the pressure of a grinding land war with Europe’s super-power, the Bank of Amsterdam overcame an acute shortage of specie with the first large-scale issue of paper money in European history, symbolic of a level of trust unthinkable in any of the European monarchies. With the founding of the Wisselbank (Exchange Bank) and the Beurs (Stock Exchange) early in the 17th century, and with the German and Italian banking houses ruined by their symbiosis with the Hapsburgs, Amsterdam became the new financial centre of Europe.

It was not until the Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought William of Orange to the English throne, followed in due course by the offices and expertise of the main Dutch trading and banking houses, that England began to reap the commercial rewards that it might have won a century earlier – if English society had not then been so institutionally backward, predatory and corrupt.